Angie Schmitt opens her book “Right of Way: Race, Class and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America” with the story of Ignacio Duarte-Rodriguez, a 77-year-old grandfather who was struck and killed by a driver while trying to cross a wide, six-lane road in Phoenix in 2018. In the three years before Rodriguez’s death, two other pedestrians died on the same stretch of North 43rd Avenue in the northwest part of the city.

Schmitt goes into greater detail and puts a face to the names of Rodriguez and others who have been killed while walking in America. She includes the tragic story of a young day care teacher and her three sons — all under the age of 5 — who were killed by a driver who was racing down Philadelphia’s Roosevelt Boulevard, a wide, high-speed arterial where 21 people died in 2018. When 27-year-old Samara Banks and her sons — Saa'mir (just a baby), nearly 2-year-old Saa'sean and 4-year-old Saa'deem — were hit, the car was traveling 70 mph.

Urban Reads presents Angie Schmitt

On Feb. 17, the Kinder Institute will host journalist and sustainable transportation expert Angie Schmitt as she discusses her new book, “Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America,” as part of the institute’s Urban Reads series.

This webinar is free, but registration is required.

In addition to Philadelphia and Phoenix, Schmitt takes readers to Portland, Oregon, where race and class play an outsized role in who is killed walking in the predominantly white city. Almost 60% of residents living in East Portland (defined as east of 82nd Avenue) are people of color, and though only about a quarter of the city’s population lives in East Portland, it’s where half of pedestrian deaths occur.

The year Rodriguez died, he was one of 108 pedestrians who died in Phoenix. The city is in Maricopa County, where 158 pedestrians were victims in traffic fatalities in 2018, a year in which more pedestrians were killed in the United States — 6,283 — than in any year since 1990. About 53% more people died while walking in 2018 than did a decade earlier.

“What can we do about this crisis — and why haven’t we done it already?”

Meanwhile, Schmitt writes in her book, fatality rates for drivers and passengers in the past 10 years have remained mostly flat in the past 10 years — rising less than 2% nationwide.

Phoenix — like Houston — is a sprawling Sun Belt city built around the automobile. Both cities, by design, largely are car-dependent; however, in the moderate-income Hispanic neighborhood where Rodriguez was killed, many people rely on public transit and walking to run errands and get around. Unfortunately, the infrastructure doesn’t reflect or acknowledge pedestrian use.

These aren’t random occurrences

Pedestrian deaths don’t just occur randomly. And in her book, Schmitt explores the patterns that have emerged as the crisis of pedestrian deaths in America has grown.

Where do they happen most? “Wide, fast arterial roads, especially in lower-income areas.”

Who is being killed? “Older people, men and people of color are disproportionately at risk.”

What kinds of vehicles are most likely to kill?: “Large trucks and SUVs.”

Where are pedestrians most likely to be hit? Pedestrian fatalities are more likely to occur in low-income neighborhoods and Black and Hispanic communities. They are also more common in the Sun Belt region of the country. (Between 2009 and 2018, 14 of the top 15 most dangerous states for pedestrians were Sun Belt states, according to Smart Growth America’s “Dangerous by Design” report.)

When are pedestrians most likely to be hit? At night.

But the number one problem, Schmitt contends, is the way commercial streets in America are designed.

Based on all of these findings, Ignacio Duarte-Rodriquez was at high risk of being struck and killed while just trying to walk from his son’s house to the store.

“He was a person with vulnerabilities in a high-risk setting who was failed by the infrastructure,” Schmitt writes in her book. “There were, after all, no crosswalks and no traffic light. There were just six lanes of roaring, indifferent traffic.”

The questions Schmitt poses: “What can we do about this crisis — and why haven’t we done it already?”

60% of the fatal crashes in Houston occur on just 6% of the city’s streets.

Schmitt cites a Smart Growth America report that showed a majority of the pedestrian fatalities in the U.S. — 52%— occur on arterials. In addition to being long, straight and wide, with high speed limits, these types of roads have a lot of commercial and residential destinations that people on foot or in a wheelchair want to reach. A dangerous combination of circumstances for people not using a car. In short, according to Schmitt: “Certain streets are designed to kill.”

Schmitt quotes Emiko Atherton, director of the National Complete Streets Coalition, on where people are dying:

“If you map out where those deaths are happening, they’re not for the most part in downtowns or neighborhoods,” said Atherton. “They’re on these roads that were never intended for people to walk on.”

The crisis is all too real in Houston

In 2019, 119 pedestrians were killed in Harris County — an increase of 120% compared to 2009, according to NHTSA data. Between 2005, the earliest date for which data is available, and 2019, Harris County’s 1,342 pedestrian fatalities account for 18% of the 7,319 deaths in Texas. Pedestrian fatalities in Harris County are 63% higher than in Dallas County (839), which had the second most during that period.

In Houston alone, 81 people died while walking in 2019. When compared to a decade earlier, that’s an increase of 125%. It’s also the highest number of fatalities in any year during the 15-year period from 2005–2019.

A search of news reports on the pedestrian deaths that have occurred in Houston in just the past two months shows they all fit the patterns of vulnerability and risk Schmitt outlines in “Right of Way.”

“Certain streets are designed to kill.”

Here’s a timeline of pedestrian fatalities in Houston and Harris County since Dec. 1, 2020, based on media reports from the Houston Chronicle:

Dec. 1, 2020: A man in wheelchair was killed in the 2100 block of Highway 6, just east of George Bush Park, a county park on the far west side of Houston. The man was trying to cross seven lanes of traffic on Highway 6 when he was hit by a driver heading north on Highway 6.

The Chronicle reported: “The driver remained at the scene and cooperated with authorities, telling them that he did not see the pedestrian.

“The victim, who was reportedly crossing the highway outside of a cross walk, was transported to the hospital where he was pronounced dead. His identity has not been released.”

A man was killed on Dec. 3 of last year by the driver of a rental van while crossing seven lanes of Highway 6, near its intersection of Empanada Drive.

Image source: Google Maps

Dec. 3, 2020: The driver of a rental van struck and killed a pedestrian at the intersection of Highway 6 and Empanada Drive, about 3.4 miles south of where the Dec. 1 death occurred.

“The driver stayed on the scene and appeared to be impaired, according to the Harris County Sheriff's Office.”

Dec. 4, 2020: The evening of Dec. 4, Kerra Elizabeth Atkins, 28, and Joshua Michael Cuellar, 20, were walking east along the westbound lane in the 700 block of Krenek Road in northeast Harris County when they were hit by an 87-year-old driver who then left the scene. Atkins and Cuellar were taken by helicopter to Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center, where Atkins died two hours later. Cuellar was left in critical condition.

“It is a very dark area and a very narrow road,” Eric Albers, an investigator with the sheriff department’s vehicle crimes division told the Chronicle. “There are no sidewalks in this area, you are either walking in the field or walking in the road.”

The driver, who police said seemed confused, was located a couple miles from the crash site.

Dec. 4: Around the same time as the crash on Krenek Road, a woman trying to cross a wide and very busy part of FM 1960 in the Cypress Station area was struck by one driver, then run over by another. The victim was pronounced dead at an area hospital, according to the sheriff’s department, which said the pedestrian was hit after she “failed to yield.”

Dec. 16, 2020: Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner released the city’s Vision Zero Action Plan, an effort to to eliminate traffic deaths and serious injuries in Houston by 2030. The plan — a culmination of 14 months of work that included data analysis, community engagement and multi-agency collaboration — followed the city’s August 2019 commitment to joining the Vision Zero coalition.

“We mapped out traffic deaths and serious injuries happening on Houston streets, and what we saw was unacceptable,” Turner said in a press release. “So, we came up with a vision, a plan, and set the goal at zero, because zero is the only acceptable number of deaths. When you see folks crossing dangerous streets to walk their kids to school, or dodging traffic to get to the bus stop, or cyclists sharing road space with unyielding drivers, we have to make a hard left turn away from the mindset that Houston streets exist solely for cars. We need to expand our outlook on mobility to recognize that streets belong to everyone who walks, bikes, drives, uses a wheelchair, and takes public transit.”

An analysis of crash locations showed 60% of the fatal crashes in Houston occur on just 6% of the city’s streets, which constitute the High Injury Network included in the plan. These are the streets and intersections with the highest density of traffic deaths and serious injuries.

It’s much the same in Denver, Schmitt notes, where 50% of all traffic fatalities occur on just 5% of the city’s street network. And in Albuquerque, 64% of road deaths happen on 7% of the city’s roads.

While 33% of Houston’s streets are located in Socially Vulnerable Communities — determined based on socioeconomic, household, racial and transportation variables — 52% of the streets in the High Injury Network are found in these communities.

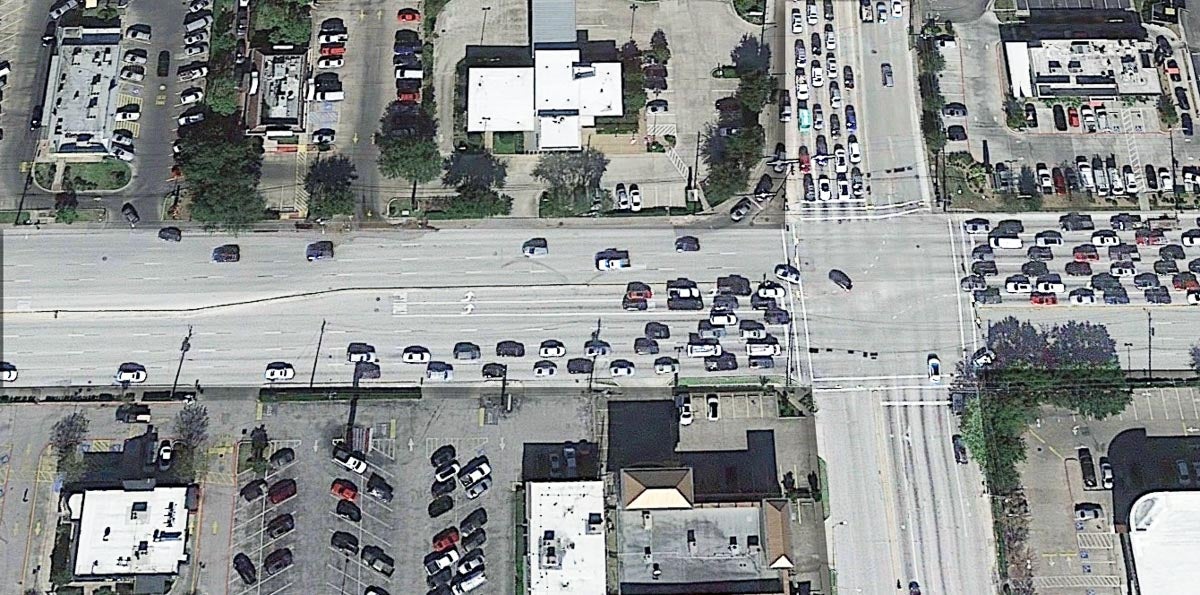

Dec. 18 and 19, 2020: Two pedestrian deaths occurred within a 24-hour period about 100 feet apart on Westheimer Road, just west of Hillcroft Avenue. Westheimer is nine to 10 lanes wide with a posted speed limit of 35 mph.

Dec. 18: A woman attempting to cross Westheimer was struck and killed by a driver later found to be intoxicated by police.

The Chronicle reported: “The victim, who has not been identified, was not in a crosswalk, police said.”

And in the next paragraph: “Officers determined the female driver was intoxicated and arrested her on suspicion of driving while intoxicated, police said.”

Dec. 19: Approximately 24 hours later, a man was killed crossing Westheimer in almost the same spot.

“First responders pronounced the man dead. He has not been identified and is believed to be homeless,” Houston police told the Chronicle.

Westheimer is nine to 10 lanes wide with a posted speed limit of 35 mph.

Image source: Google Maps

Dec. 27, 2020: A man died after being hit by the driver of an SUV in the 8800 block of Synott Road in southwest Houston. The driver fled the scene. Synott is a long stretch of road with two northbound lanes and two southbound lanes divided by a shallow drainage ditch.

Dec. 30, 2020: A suspected drunk driver hit a pedestrian at Main Street and South Loop 610. The victim, who was taken to the hospital, later died. Before hitting the pedestrian, the driver was involved in a collision with another vehicle.

Jan. 17, 2021: The driver of a pickup struck and killed a man on North Shepherd Drive and then fled the scene.

According to the Chronicle: “The man was not in a crosswalk when he was hit around 10:30 p.m. along North Shepherd Drive, near Thornton Street, police said.”

Jan. 17: In the same story, it was reported that: “Hours earlier, police investigated another death of a pedestrian. A woman walking on a bridge along FM 1960 around 8 p.m. was hit and killed by a driver who did not see her, police said.”

Jan. 23, 2021: A pedestrian was killed in a hit-and-run crash in the Upper Kirby area.

A man died after being hit by the driver of an SUV in the 8800 block of Synott Road in southwest Houston. The driver fled the scene.

Image source: Google Maps

Blaming the victims

Schmitt also examines blaming the victim, which she calls a common phenomenon surrounding pedestrian deaths in a driving culture such as the United States’:

“Police, juries, the media, and even traffic safety officials are all susceptible to what pedestrian advocates call windshield bias. This bias is apparent in the language used by traffic safety officials charged with protecting the public, who emphasize pedestrians’ safety responsibilities to an extreme degree while minimizing the responsibilities of drivers.”

In the Houston pedestrian deaths mentioned above, the reports in the Chronicle amount to “traffic briefs” based on police reports, which often call out the victims for “failing to yield” or “not being in a crosswalk” when they were run over, even in hit-and-run cases. By the way, in 2019, drivers fled the crash scene in almost 35% of pedestrian fatality cases in Houston. Since 2005, hit-and-runs occurred in 34% of crashes that killed pedestrians in the city. In that 15-year period, 32.5% of pedestrian fatality crashes in Harris County were hit-and-runs.

Schmitt says when a news story about a pedestrian fatality includes information such as the victim “not being in a crosswalk,” the implication is that the pedestrian was jaywalking and therefore is at fault. But often there’s no follow-up to these stories or further digging. More importantly, Schmitt argues, “is that reporters rarely ask if there was even a crosswalk anywhere nearby.”

In 2019, drivers fled the crash scene in almost 35% of pedestrian fatality cases in Houston.

On the heels of the NHTSA’s release of 2018 statistics that showed that year to be the deadliest in three decades for people riding bikes in America — 857 dead — the National Transportation Safety Board dropped a report on bicycle safety that caught a ton of flak from critics who found the whole thing smelled of victim blaming. Two of the report’s three key recommendations focused on the need for cyclists to wear helmets and conspicuous clothing. It also suggested bicyclists could do a better job of not getting killed by more closely following traffic rules and traffic signals.

Peter Flax addressed the problems of the report for Bicycling magazine:

“The collective message is that riders often are naughty and need to take greater responsibility for their own safety. Instead of seeing what cyclists really are — the victims of systemic problems that desperately need fixing—the NTSB frames riders as the agents of their own demise.”

In “Right of Way,” Schmitt addresses similarly tone-deaf recommendations from the NHTSA for pedestrians and drivers to consider to decrease the risk of accidents. For pedestrians, these include wearing brightly colored clothing, making eye contact with drivers, not texting and carrying a flashlight.

The No. 1 recommended safety rule for drivers?

“Look out for pedestrians everywhere, at all times. Safety is a shared responsibility.”

Schmitt finds the emphasis on shared responsibility and the behavior of pedestrians to be “odd given the enormous power imbalance in play. A Toyota Sequoia, for example, weighs six thousand pounds. Official sources, however, say that the driver of this vehicle has more or less equal responsibility for pedestrian safety as a 111-pound woman trying to cross the road.”

To learn more about the dramatic rise in pedestrian deaths in the U.S. during the past decade, including the geography of risk and killer cars, as well as programs and movements that are beginning to respond to the epidemic, be sure to register for the Feb. 17 Urban Reads event featuring Schmitt. The webinar is free, but registration is required.