The prescient Peter Drucker foresaw privatization, the importance of customer service and the nonprofit sector, and the decentralization of companies (“Do what you do best and outsource the rest.”) The towering figure in the field of business management also coined the term “knowledge worker.” More than 30 years ago — at the age of 80 — Drucker said, “commuting to office work is obsolete.” Drucker died in 2005, so he never saw his work-from-home vision realized.

The idea of telework has been around for decades. During that time, a number of companies took unsuccessful stabs at implementing remote work. But for most, it took a public health crisis like the coronavirus pandemic to put the concept into practice. In March, stay-at-home mandates implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19 forced the hand of businesses that may have been reluctant to adopt work-from-home (WFH) policies because of fears about its impact on productivity, innovation, collaboration and company culture.

But as the WFH experiment continues for close to 10 months now, most workers and managers see working remotely as a permanent change — in part at least — to the work-life equation. Humanity’s ability to quickly pivot, adapt and confront the threat of the coronavirus was most impressively displayed in the creation of several vaccines in record time. Also impressive has been how quickly co-workers saw each other master the art of video conferencing and Zooming — some more quickly than others.

A Pew Research Center report released in December showed almost three-quarters (71%) of workers were working from home all or most of the time since the pandemic began, compared to just 20% who did so before COVID-19. More than half (54%) of those who can telework would like to continue doing so all or most of the time after the pandemic. Over 75% said it’s been easy to meet deadlines and complete projects on time and to have the technology necessary to do their job. Of note: The survey also highlighted the class divide between those who can work remotely and those who cannot. Over 60% of those with a bachelor’s degree or more reported they could do their work from home, while only 23% of workers with less than a four-year degree could do so. The majority of low- and middle-income workers have jobs that can’t be done from home — 76% and 63%, respectively.

In the 2021 edition of “Emerging Trends in Real Estate” — a long-running forecast report from the Urban Land Institute and PwC — 92% of survey respondents reported that at least some of the workplace changes made in response to COVID-19 would become permanent even after an effective vaccine is widely available and administered. And more than 94% agreed that “In the future, more companies will allow more employees to work remotely.”

It’s estimated that employees could save an average of 227 hours a year (about 28 workdays) in commute times alone by working remotely. The question is whether they can match the productivity levels of working in an office while working from home. So far, things have gone better than many may have expected before the pandemic, and efficiency should only improve going forward. A hybrid of WFH and in-person could be the solution.

An institutional equity investor interviewed for the “Emerging Trends” report said, “There seems to be almost an optimal productivity situation where working in the office three or four days a week and then remotely one or two days a week is actually more productive than working in the office five days a week or being out of the office all five days of the week, so we’re discussing greater flexibility around working remotely.”

Assuming that those who have been fortunate enough to work remotely will continue to do so on a full- or part-time basis, how will our homes and living spaces change to better accommodate so much more time spent in them?

‘The House of Tomorrow’

In his 1949 animated short “The House of Tomorrow,” Tex Avery takes viewers to the year 2050 to tour a typical home of the future — one that’s loaded from top to bottom with appliances and design features that promise to minimize the drudgery of daily life. “Pre-fabricated and ready to set up,” the prototype “smart” house Avery dreamed up is outfitted with technological advances such as a machine that (ostensibly) never tires of answering the endless stream of questions that flow from the family’s young son; a sandwich-making robot that deals slices of bread and cold cuts like playing cards; an orange-juicer that spits extracted seeds into a spittoon with a satisfying cartoon “plink!”; and to answer the question of what happens to the interior light when the refrigerator is closed, a model equipped with an in-the-door window.

Those who’ve seen it know “The House of Tomorrow” is a satirical — and undeniably dated — take on both the increasingly dominant role played by technology in American life and the American family itself, with all of its fantasied perfection, in the years following World War II. All is not perfect in this home of the future. The innovative appliances fail disastrously; the father is a heavy drinker with a wandering eye who has a weirdly intense dislike for his mother-in-law; and the mother seems understandably unhappy.

Avery, who directed the debuts of Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny while at Warner Bros., was instrumental in creating and advancing the Looney Tunes style and humor, with its mile-a-minute action and high frequency of jokes and gags. He spent his career making cartoons that were the screwball antithesis of Walt Disney’s more subdued productions, and “The House of Tomorrow” is no exception. One of the more striking things about the short is the jarring juxtaposition of the straightlaced narrator (Frank Graham) and the animated high jinks.

When Avery made the short for MGM, the nation was several years into a period of unprecedented economic prosperity — though not one enjoyed equally by all Americans — following WWII. By 1949, the stout optimism experienced by many in the afterglow of the allied victory had faded.

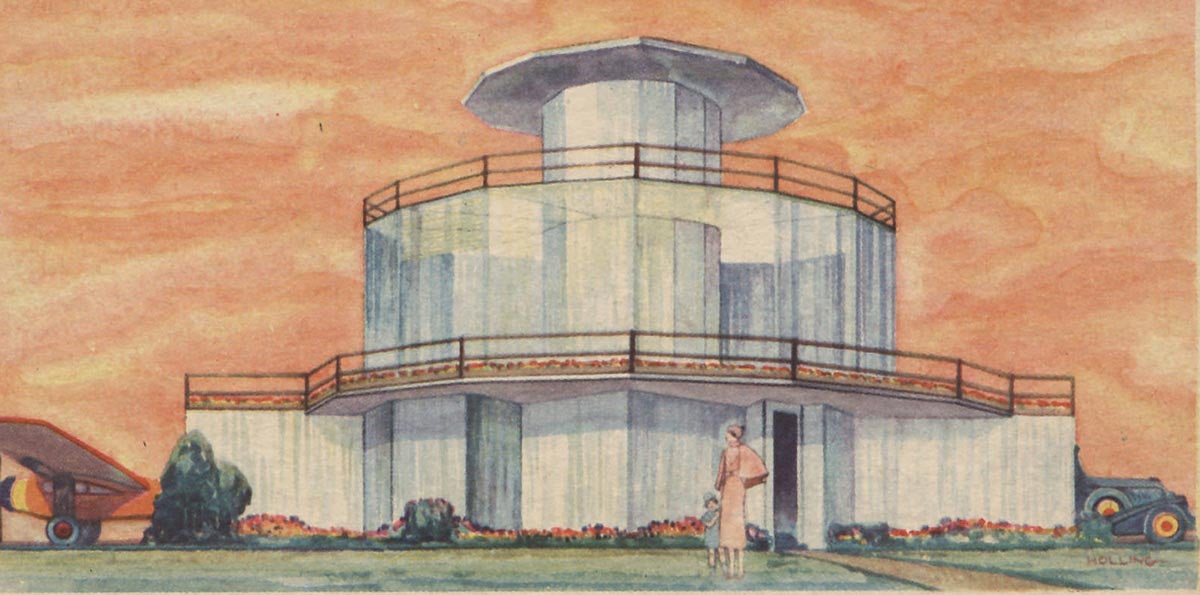

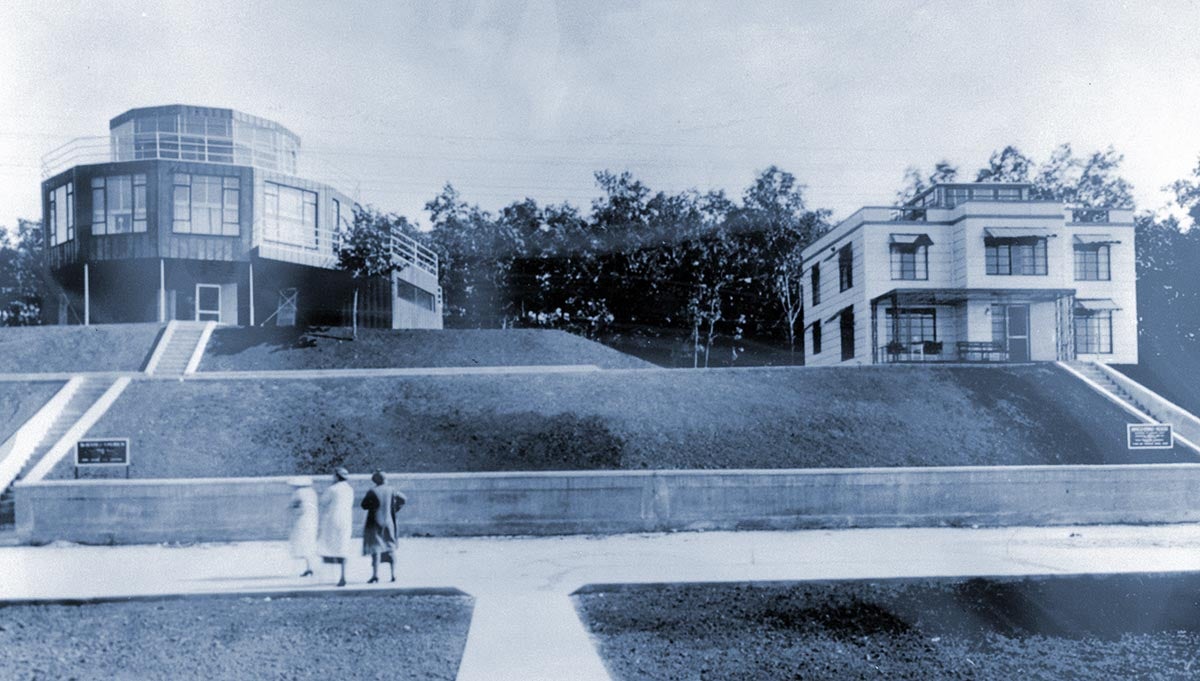

The World’s Fair Homes of Tomorrow

In 1933, while the U.S. was very much in the thick of the Great Depression, technological innovation was the focus at the Chicago World’s Fair. With the slogan, “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Adapts,” and an emphasis on technology and progress, fair exhibits provided visitors a glimpse of a “happier not-too-distant future, all driven by innovation in science and technology.”

One such optimistic glimpse was the Homes of Tomorrow Exhibition, which comprised 12 homes that showcased modern design ideas, innovative building materials (porcelain-enameled steel, pressed-board siding) and prefabrication techniques. Special function rooms such as the “laundry room” — something unfamiliar to Americans at the time — were also included.

The idea was to use the homes to promote industrial advances in building materials such as resiliency and convenience (no need to repaint a steel house). Most were sponsored by corporations that produced the materials used in the construction of the homes or sold furnishings for the interiors, including American Rolling Mill Co., Ferro Enamel Corporation, Rostone Inc., Mayflower Wallpaper, Wieboldt Department Store — even the State of Florida!

Chicago architect George Fred Keck’s 12-sided “House of Tomorrow” had a steel structural system, an open floor plan, a floor-to-ceiling privacy curtain system and floor-to-ceiling windows, which earned it the nickname “The Glass House.” Keck’s house and others were equipped with the very latest conveniences and innovative home appliances, including central air-conditioning and electric refrigerators and dishwashers. Keck’s also featured an attached garage with an automatic opener and an airplane hangar(!).

Enter today’s homes of tomorrow

In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic has changed the way we live, work and learn. Almost as soon as it began, there was increased demand for homes that could accommodate new needs for space to work, as well as work out. Demand for home-learning spaces increased too. In response to the pandemic, homebuilders such as Lennar, Pulte, DR Horton and KB Homes are rolling out designs better suited for life during and after the pandemic. And the marketing materials are reminiscent of those homes of tomorrow from almost a century ago.

In the 1930s, the Homes of Tomorrow had innovative appliances such as dishwashers, whereas today’s homes of tomorrow have energy-conscious appliances, doors with Wi-Fi-enabled deadbolt locks, smart thermostats and task lighting. Open floor plans are falling out of favor as the preference shifts toward more-defined office space and workspace.

“Builders are responding to the current housing boom with new home layouts better suited for households living through a pandemic,” Gregg Logan, managing director of the real estate advisory firm RCLCO, wrote in an article about the coronavirus' impact on the housing market. “New homes that better accommodate working from home. Home learning is also being better incorporated into new home designs, with ‘learn-in’ kids’ bedrooms, school room loft designs, and basement study halls being offered as options. While many gyms remain shut down or only partially open, builders are offering dedicated space for at-home workouts, in the house, garage, or basement.”

Design changes to accommodate working from a home office include built-in desks, noise insulation, enhanced lighting, pre-wired Wi-Fi and outlets with USB chargers. To take “more-defined” to the next level, some builders are offering designs with half-baths, kitchenettes and exterior entrances (one thing Tex Avery’s cartoon got right), as well as flex spaces that can be used as both an office and home gym or as an office/meeting space.

The pandemic also reminded us of the importance of good hygiene such as frequent hand-washing and made us more attentive to disinfecting surfaces in our homes. Small modifications like installing a touchless faucet in the kitchen and buying an automatic hand-soap dispenser have been a big help in reducing the spread of germs in general at home. There has also been a greater demand for self-cleaning toilets, air filtration for improving indoor air quality, anti-microbial countertops (nonporous quartz) and even bacteria-resistant paint.

According to a survey of home design trends from the American Institute of Architects, home office space, outdoor living areas and mud rooms were the most popular “special function rooms” with clients in 2020. Among the individual architects or firms that build custom homes or do renovations that participated in the AIA survey, 68% said requests for home offices went up. Requests for sunrooms or three-season porches were reported by 21% of respondents and mud rooms or “drop zones” increased in popularity.

For the first time, the AIA survey included questions about “additional multifunction rooms or flexible space,” and 43% of respondents reported requests for designs that incorporated such spaces. Almost a quarter (23%) reported clients asking for a dedicated space for exercise or yoga.

Running contrary to a multi-year trend in increased demand for infill and higher-density development, the results of the survey released in mid-December showed a decline in the popularity of those developments and mixed-use facilities. Meanwhile, demand spiked for multigenerational housing and more sustainable and walkable neighborhoods.

“The uneven impact of the pandemic on specific construction sectors is nowhere more apparent than in custom residential,” said AIA Chief Economist Kermit Baker. “Though the initial impact of the pandemic hit residential architects hard, a stay-at-home lifestyle and the desire for more space and less density has increased homeowners’ desires to modify their accommodations.”

Photo courtesy of Pulte Homes

Mindful, informed planning is necessary

A century from now, people will look back and wonder how we ever lived without these amenities. They’ll seem as basic and commonplace as the air-conditioning and dishwashers celebrated as cutting-edge in the 1930s homes of tomorrow.

Though given the current trajectory of climate change and the continued suburbanization and exurbanization that has only been accelerated by the current housing boom, 100 years from now feels too far out and precarious for predictions. And don’t forget, there are downsides to the changing nature of work, including further strain on city budgets if businesses don’t need as much office space in central business districts in the future. For example, the office vacancy rate in downtown Houston is 18%; second only to Dallas among the top 10 metropolitan areas in the U.S.

“People are now betting on suburban office, driven by the fact that millennials are moving out of urban cores for locations where they can get housing,” the CEO of an investment management company said in ULI’s “Emerging Trends” report, which shows suburban offices jumped significantly in the 2021 survey, moving to No. 10 among 24 potential “subproperty types” in terms of investment prospects. That’s up from 21st in last year’s survey. Central-city office space fell from No. 8 to No. 20.

Whether people move farther from central cities to afford a home or to afford more space, the resulting climate change and associated environmental risks are the same. Emissions from driving are now the No. 1 cause of greenhouse gases in America. Sun Belt metros like Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta and Phoenix have used sprawl to contain housing costs, but low-density single-family suburban developments are adding to car-dependent residents’ cost of living and the environmental price that comes with annual increases in vehicle miles traveled.

Get Urban Edge updates

If you’re interested in stories that explore the critical challenges facing cities and urban areas — from transportation, mobility, housing and governance, to planning, public spaces, resilience and more — get the latest from the Urban Edge delivered to your inbox.