On a personal level, the memory of the day—and the distress—remains fresh. We were stuck in our home, not having a means to travel out in the snow and ice-covered roads. As the hours without electricity passed, our house resembled more a refrigerator than a sanctuary from the elements. The anxiety only mounted as we tried to keep our four-month-old baby and a two-year-old toddler warm and calm during the escalating situation. And yet we were among the fortunate who endured the disaster relatively unscathed.

On the communal level, it was a vivid reminder that climate resilience in Houston encompasses more than flooding, heat, or storm surge—that our communities are greatly dependent on infrastructure resilience and the political will of not only local leaders, but also state officials, given the history behind Texas’ secession of the energy grid and the negligent planning behind these systems.

The impact of this disaster, while widespread, reinforced many underlying inequities in the region. Damages were more pronounced in low-income communities with older homes and more people of color—many of whom have been hit especially hard by three major recent disasters—Winter Storm Uri, COVID-19 and Hurricane Harvey.

The Kinder Institute for Urban Research, in partnership with Harris County’s Community Services Department, analyzed the damage from Winter Storm Uri and the compounding effects from multiple crises. The report, which was made public today, also examined a set of community resilience indicators to better understand what vulnerabilities distinct communities face and how these issues are intertwined for emergency management and preparedness efforts.

Researchers also spoke with community leaders and stakeholders to learn more about the on-the-ground realities that residents confronted amid these disasters. What our data shows and what those groups shared can be distilled into a few key conclusions.

Some of the hardest-hit areas were already vulnerable.

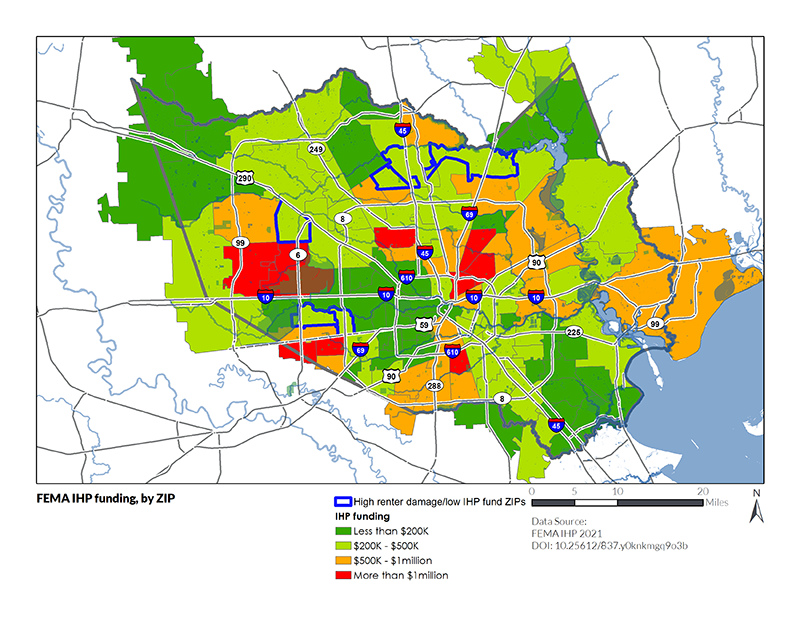

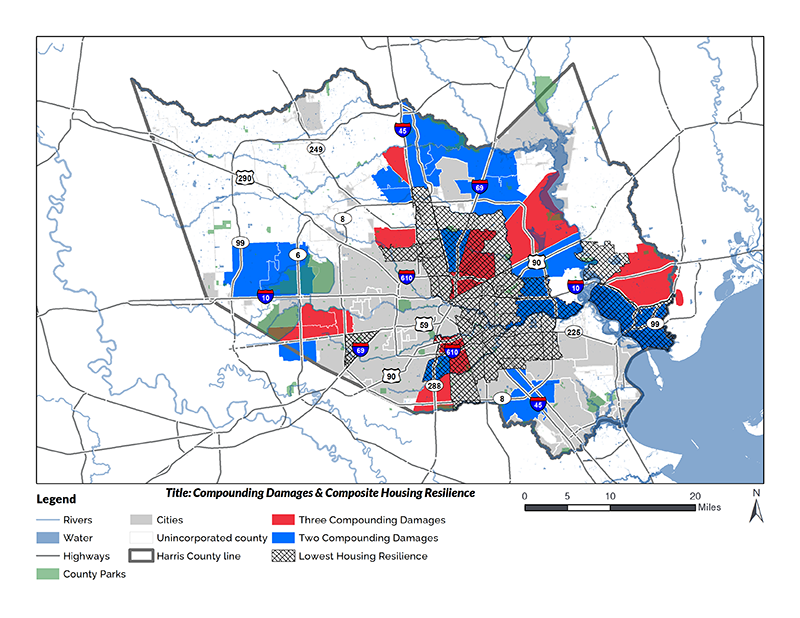

By looking at these compounding effects, we identified 13 ZIP codes that were among the worst affected by all three disasters—as measured by the volume of unemployment claims during COVID-19 and the number of registrants for FEMA’s Individual and Household Program for both Harvey and Uri.

These neighborhoods are concentrated on the periphery of the Houston city limits and in many unincorporated communities of Harris County, with more urban concentrations in southwest, northeast, and south central Houston.

We need a tailored approach to resilience and recovery.

Different resilience challenges mean that disaster response strategies should be tailored for each community. For example, people age 65 and over are more likely to be disabled and have limited transportation options. Preparedness efforts in communities with those populations could include transportation services to help residents access emergency shelters.

Meanwhile, communities with limited English proficiency are more likely to experience unemployment, not have access to a car, and have adults lacking a high school diploma. Emergency response efforts can focus on bringing multilingual outreach through trusted grassroots organizations to assist in submitting damage reports to federal authorities and accessing recovery funds.

We need proactive weatherization efforts coupled with trusted community engagement.

Weatherization programs and other measures implemented during the “disaster off-season” will help low-income communities prepare for future disasters. Communities impacted by compounding damages and demonstrating low housing resilience are ideal candidates for prioritization of preventive measures. These communities include: Fifth Ward, Kashmere Gardens, Trinity / Houston Gardens, Settegast, East Little York / Homestead, Greater OST / South Union, Eastex / Jensen, Galena Park, Jacinto City, Northshore, Baytown, Sunnyside, and South Park.

Before the next disaster, there is also a need for deeper engagement with residents in all neighborhoods, but particularly those that are most vulnerable. This is where we need to bring together trusted grassroots organizations as well as more informal networks into the mix to connect residents to preparedness, response, and recovery services, given the low concentration of civic and social organizations in the county—0.34 organizations per 10,000 people—compared to the national average—0.76 per 10,000 people (In the report, see Resilience Indicator 12: Connection to Civic and Social Organizations.)

The need for community outreach also extends to the county’s cadre of small landlords, who are more likely to have tenants who feel the brunt of these crises. There is a need to help renters advocate for themselves following a storm as well as help connect landlords to resources.

We can put cash in hands, but it will only do so much.

Several months after the winter storm, the greatest needs were not for building repairs but for basic necessities, such as food, utilities and assistance with rent/mortgage payments. Cash assistance can be the difference between a household choosing to pay for a repair and choosing to feed a family. Recovery funds could allocate a set aside amount for rent and utility assistance, preventative measures or repair assistance, or help homeowners meet their insurance deductibles.

At the same time, cash assistance can be an easy and effective policy response but may not be sufficient to cover the gamut of needs across Harris County throughout a sustained period of time. It is only one measure among many that could make a difference during the next disaster.