The foundational forces in any given market are supply and demand. For the single-family housing market, the underlying factor driving demand growth is the household purchasing capacity, which is driven by wage growth, household savings rates and cost of borrowing — the latter is buoyed by healthy capital markets.

The underlying factors driving the supply of single-family homes are the costs of land, materials and labor. All factors being equal, in any given individual market, a healthy market — ones that’s at equilibrium — grows at the same pace as the broader economy and, therefore, on par with inflation factors. Extreme volatility or aberrant changes in a market’s value is an indication that underlying factors are no longer in equilibrium. This can create a ripple effect that impacts other external markets.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

Such aberrant changes currently are underway in the single-family housing market. Those aberrant changes are driven by some of the same issues that caused the 2008 financial collapse. However, some current issues differ from 2008, which will lead to a different outcome than the housing collapse that preceded the Great Recession.

Demand is far outpacing supply

The biggest variable causing the market for single-family homes to roil on Main Street is the inability of builders to deliver new housing supply fast enough to keep pace with demand. The effects of the Trump administration’s trade policies led to an increase in the costs of lumber, sand, concrete, steel and aluminum — a near universal increase in the cost of materials needed to build housing units. Furthermore, the previous administration’s immigration policy constrained labor markets — fewer potential employees drives up the cost of hiring the available labor force. On top of that, the previous administration’s inability to effectively manage the COVID-19 crisis led to workplace shutdowns; virtually assuring that supply would not meet demand until the end of the pandemic.

COVID-19 has certainly caused a segment of the population to lose their jobs and many households to suffer from a decrease in household income. But let’s set aside households in forbearance for a moment. Eventually, their market impact will be felt, but that could be a year from, so it’s not a factor in the immediate marketplace.

The biggest factor driving an increase in demand for housing is population growth. Every year, new college graduates enter the workplace, households grow in size, and immigrants are allowed into the county. The pandemic had two demand-side consequences. One was the change in household budgets — savings rates increased as vacations were delayed, big-ticket purchases were waylaid and retail spending plummeted. Also, to keep the economy moving, fiscal policy demanded a decrease in the national interest rate, which increases the ability for households to qualify for larger mortgages.

Increased savings and the ability of a household to qualify for a larger mortgage, combined with a nationwide drop in new supply is causing some single-family markets around the country to witness two- to three-fold increases in the year-over-year value growth of homes. This is good for single-family sales brokers, whose fees are a percentage of a home’s value. It’s good for local jurisdictions and school districts that rely on tax-assessed value increases to fund local government. And it’s also good for those who are able to sell their home and downsize to a smaller unit. However, in the long term, it’s pretty much bad for everyone else to have such an aberrant, unsustainable spike in values. Some homeowners who have upgraded to a larger home may feel good now, but once values come back to earth, it may take many, many years for the value of that home to get out from being underwater based on their mortgage.

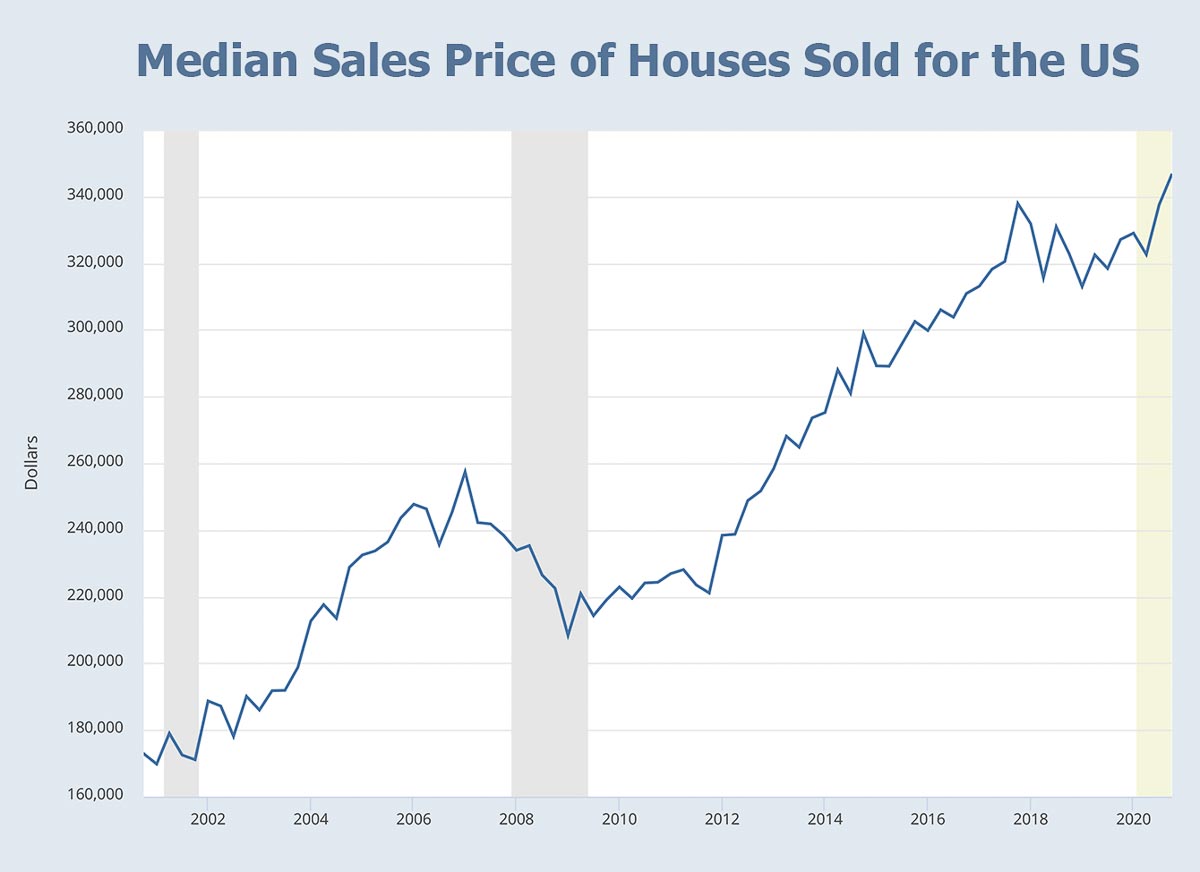

Source: Graphic courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, based on data from the Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development

Changes to how homes are appraised

Another contributing factor that should be acknowledged is the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s loosening of its national appraisal standards to allow households to qualify for larger mortgages as values have grown. Only time will tell if this is a prudent decision and to what degree a relaxing of standards may contribute to future market health.

On the flip side of this policy, the FHFA is also looking at completely overhauling the premise of appraisals in the mortgage underwriting process. As it stands, the appraisal industry charges itself with determining value based on what a buyer is willing to pay. This runs contrary to what the lending community needs for underwriting mortgages, which is the price a household should pay — a completely different question. We will see how this conversation plays out over time.

Recently, the Biden administration announced a $15,000 First Time Home Buyer Assistance Tax Credit as a proposed measure to help restore equilibrium to the single-family housing market. Under normal conditions, the U.S. housing market would benefit from a demand-side boost; however, at present, this is off-key if the administration’s goal is to address the immediate needs of the single-family market. It’s the supply side of the equation that needs an immediate fix, but supply-side housing fixes are much harder to make. It will be interesting to see how the Biden administration handles the previous administration’s policies on trade and tariffs and immigration, as these will have far more impact on the immediate needs of the housing industry than the promise of a homebuyer tax credit.

The other demand side factor that needs further discussion is the cost of borrowing, i.e., interest rates. The run-up to the financial collapse in the early 2000s was largely driven by sustained lower-than-normal interest rates. Diminutive underwriting standards provided the spark that caused the explosion, but low interest rates were the fuel.

When the 2000s housing market exploded, the financial system seized up when log-jammed banks were unable to continue lending because the secondary mortgage market stopped buying new mortgages. The Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve were left scrambling to reopen the banking system because the ultimate solution — for the U.S. government to buy the loans — was too slow in kicking in.

At present, the Federal Reserve is the single biggest buyer of all U.S mortgages, to the tune of $2–$3 billion a day — each and every day the markets are open. They are electing to utilize their market activity to purchase the two main middle-market tranches, which in large part, also ends up setting market pricing for the slightly below- and above-market quality mortgages. As such, the Fed has stated they intend to maintain this fiscal policy until inflation reaches a sustained level above 2%. Here’s the bottom line: as long as the Fed maintains this posture, there should not be another global housing market meltdown and the mortgage market should sustain liquidity and capital flow, albeit with somewhat normal market fluctuations like we witnessed over the past few weeks in the bond markets.

The future effects

As to the looming forbearance and mortgage delinquency rates. Nationally, under normal market conditions, single-family delinquency is between 1 and 2%. Many major markets around the country have delinquency rates that are two to three times the normal rate. (The general consensus seems to be that the moratoriums on evictions and foreclosures may be lifted when analysts predict the market could reasonable absorb and process foreclosures at one-and-a-half to two times the standard delinquency rate.)

The long-term market consequence of this will be that some current homeowners will be pushed into the rental markets, and some existing renters will graduate to homeownership. Our housing stakeholders should be prepared to help manage the consequences with homebuyer training classes for the new entrants to the single-family housing market, and counseling and programs to soften the blow on household composition for families downsizing to the rental markets.

Unfortunately, the woes of the single-family homebuilders are also felt by multi-family developers, which have witnessed a 15–25% increase in building costs. Many projects that at one time might have been financially feasible are being scrapped or delayed until material costs come down and trade issues are settled. The consequence will be a perpetual increase in rental rates for apartment units, which will prevent renters from saving enough to qualify for a mortgage. That’s if student loans weren’t already keeping them from homeownership.

It’s imperative that the housing industry makes policymakers aware that their focus should be on ensuring that new housing supply can at least keep up with new demand. If not, the housing affordability crisis will only deepen further, placing a pillar of the U.S. economy — and each household’s largest expenditure — in jeopardy.

Jonathan Campbell is interim executive director of the Southeast Texas Housing Finance Corporation (SETH), which provides financing and rental options for low- to moderate-income renters and homebuyers.

The Kinder Institute for Urban Research and SETH are part of the Houston Housing Collaborative, a diverse collective of nonprofit organizations, research institutions, financial institutions, public and private universities, builders, developers, neighborhood associations, advocacy groups and individuals working to fill the need for safe, affordable housing in Houston and Harris County.