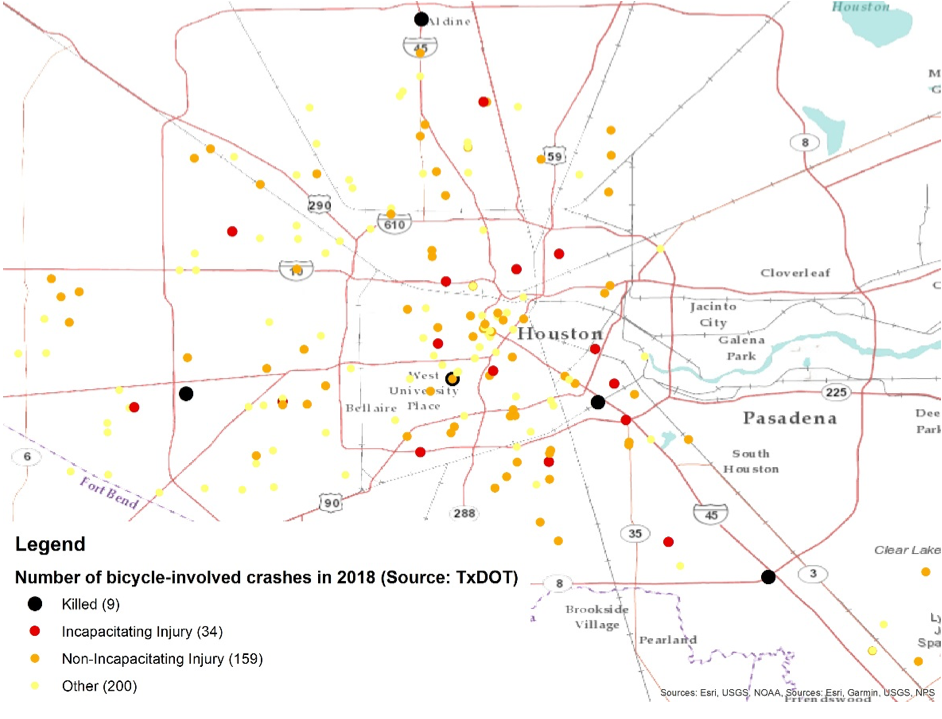

Biking on Houston streets, even for those who do it daily, can be a terrifying experience. Just halfway through 2018, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) recorded a total 476 bicycle-involved crashes in which nine bicyclists were killed and 193 were injured. But those incidents do not fully capture the extent of how dangerous it can be. Official crash data don't include incidents where people narrowly avoided collisions. Some harrowing experiences about these close calls were captured in a study that collected information on volunteers’ travel during one week in March 2017.

Efforts to improve safety often focuses on behavior but analysis of existing infrastructure and future planning like the Houston Bike Plan are important not just for offering a vision of connectivity but for urgently needed safety improvements. Based on the travel diaries' results combined with official crash data and trip information from a Bike Month Challenge in 2016, the Kinder Institute's latest report, From Close Calls to Crashes, focuses on bicyclist safety and stresses the importance of implementing the Houston Bike Plan.

Locations of crashes involving people riding bicycles in 2018, per TxDOT.

The study finds that for bicyclists, roughly 23 percent of bicycle-related crashes between 2009 and 2015 occurred on local streets, mostly located along residential areas. With the lack of designated and protected bike lanes in the city, most people who ride bicycles plan their routes around low-volume, low-speed streets such as these. But riding on high-volume, high-speed streets are often necessary to get to many important destinations like jobs. Although most near-miss incidents and crashes happened in areas with higher bicycle traffic volume, some do happen in areas with less connected or non-existent bike infrastructure. The study also looks into these locations and how they are connected to the existing and planned bikeways.

Although final decisions on specific design and location will need to consider additional analysis and public engagement, the Houston Bike Plan outlines strategies for implementation by identifying programmed projects, potential short-term opportunities, key connections and long-term projects. Programmed projects are those already in development by the city, TxDOT and other agencies while long-term projects involve investments that can truly achieve a comprehensive bicycle infrastructure network throughout the city. Meanwhile, potential short-term opportunities are projects involving reallocation of excessively wide lanes or designating low-speed, low-volume streets as shared routes.

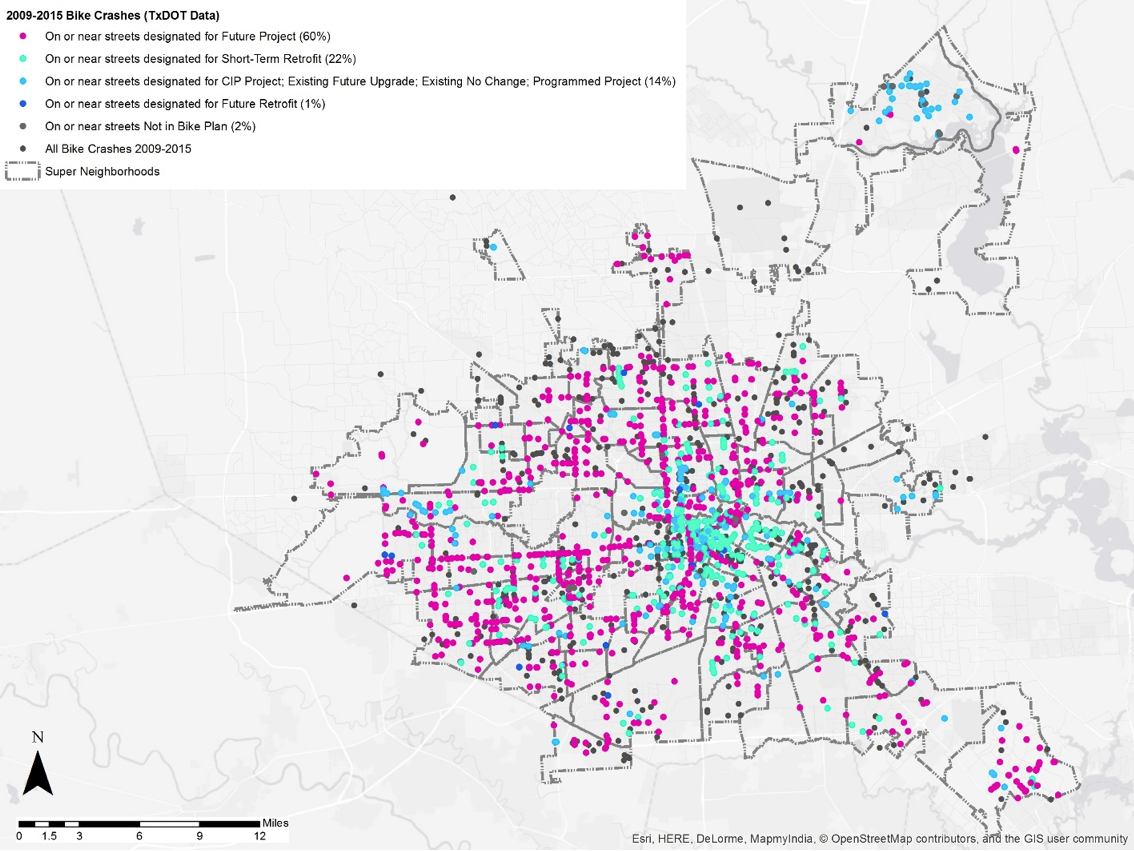

The image below shows where crashes and near-miss incidents happened over a several-year period when compared with types of designated projects identified in the plan. It also shows that bike crashes occurred mostly on or near streets designated for long-term future projects. These projects can connect different neighborhoods and are likely those that take people to places along major streets like Westheimer, where there are a lot of commercial and office buildings.

Of the 2,214 crashes between 2009 and 2015, approximately 60 percent of those occurred on or less than 1 mile from streets designated for long-term future projects in the Houston Bike Plan and 22 percent of those crashes were along streets designated for short-term retrofit projects. These short-term projects include low-cost strategies like restriping or adding signage. Such projects can increase the visibility of safe spaces for vulnerable road users while at the same time sending a signal to drivers to watch out for other road users.

While the long-term projects have bikeways connectivity in mind, the short-term projects aim at improving safety in existing bikeways or routes. Depending on the context of the built-environment, some projects can be more urgent than others, which is why the mayor recently requested identification of the 10 most dangerous intersections in Houston streets. In response to this call, LINK Houston provided an analysis using 2016-2017 TxDOT crash data. According to their analysis, the most pedestrian and bicyclist deaths occurred in City Council District H, followed by Districts B and D. These are districts on the north and southeast of Houston.

The Kinder Institute study also finds that approximately 44 percent of bicycle-related crashes between 2009 and 2015 occurred within Harris County’s Precinct One jurisdiction--another reason why the recent collaborative effort between the county and the city to allocate funding for safe street infrastructure this year is crucial. Implementation of the short-term retrofit projects in the Houston Bike Plan located within the district’s jurisdiction can cover up to 48 percent of the total projects listed in the bike plan.

Our study further highlights that when near-miss incidents and crashes cluster, there’s a need for implementing strategies and projects already outlined in the bike plan in those areas. These crashes are not only tragic but have related economic and societal impacts. Motor vehicle traffic is the number one leading cause of violent deaths for people ages 5 to 24 years old in 2016. For Texas, the economic consequences of pedestrian and bicyclist deaths account for $716 million and $84 million respectively.

Efforts to prevent bicyclists’ deaths tend to focus on individual behaviors of people riding bicycles, the very same people that are more likely to sustain serious injury and even death if struck by an automobile. But factors such as the built environment matter as well—availability of bikeways, its conditions, and connectivity to important destinations are elements that can prevent further death as well as measurable and immeasurable costs.