Back in 2010, news started circulating among the Seattle-area press that the 98118 zip code - which contains the Columbia City neighborhood - was named by Census as the most diverse zip code in America.

The news struck University of Washington researchers Ryan Gabriel and Tim Thomas as hard to believe. On paper, the area was definitely diverse - 59 different languages are reportedly spoken in Columbia City - but it just didn't feel like it to the doctoral candidates.

"We've been through that area, and we had a sense of what it's like," Gabriel says. "When you go down there, it's not necessarily diverse. People aren't necessarily crossing racial boundaries. So we decided to investigate it in a scientific way."

As it turns out, the diversity designation wasn't exactly true (the misinformation percolated through the blogosphere, despite the fact that the Census doesn't rank neighborhoods by diversity). But it spread nonetheless because it to some, it really did seem believable. Immigrants in Columbia City speak many languages, including Chinese, Somali Spanish, Vietnamese, Tagalog and Khmer, the Seattle Times wrote. At the same time, "close to a third of the population is African American, an influx that started in the 1950s, and another third white, including remnants of the Irish and Italian immigrants of the early 1900s," the newspaper wrote.

The University of Washington researchers decided to give the area - and others within Seattle that are considered "diverse" - a closer look. Their analysis includes measurements of where people of different races live within the neighborhoods, as well as methodical, on-the-ground observations of the built environment.

What Gabriel and Thomas saw was a scenario vastly different from the slew of media reports that touted the diversity of Columbia City and Seattle by extension. "We've had a lot of conversations about Seattle," Gabriel says. "It's a highly-diverse city in some ways, but as you kind of walk the city, you experience a real sense of separation between racial groups and class levels as well."

What they discovered was that segregation persists even within Census tracts that are racially diverse. Neighborhoods that had a mix of different races at the Census tract level - geographical areas that include about 4,000 residents - often had dramatic signs of segregation.

Communities that seemed to have a mix of residents on paper actually housed racial groups that remained tightly clustered. They called the phenomenon "micro-level segregation."

In Columbia City, for example, the researchers found the west side of the tract had lots of immigrant markets and fast food restaurants. On the predominantly white side of the tract near the bay were five-star restaurants serving $60 entrees. "The separation of amenities is really stark," Gabriel says. "We think these people live in separate social spheres, even though they're in the same Census-defined area."

The team looked at other seemingly diverse areas too. They found in many instances, topographical features separated communities by race, as did transportation features like major thoroughfares.

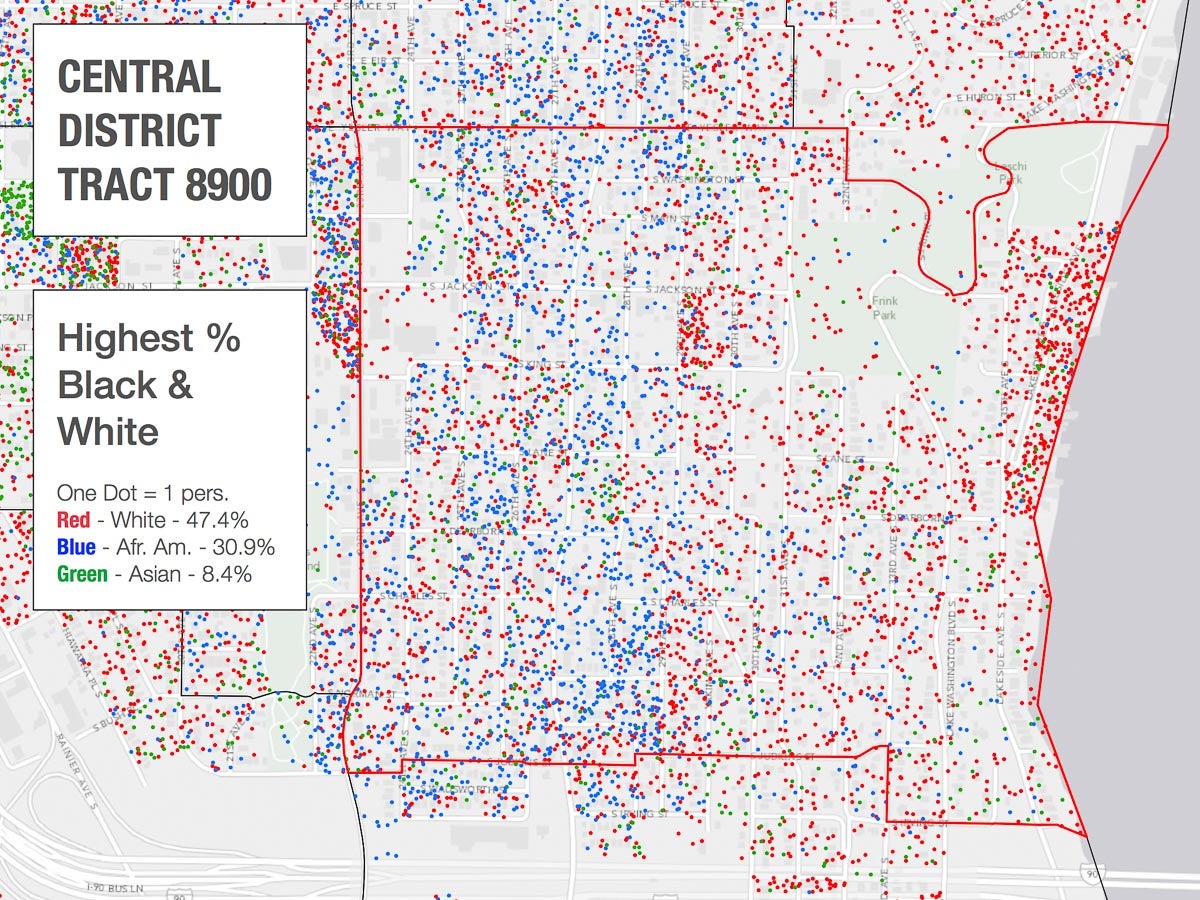

In this central Seattle tract, white residents cluster to the east along the waterfront. Black residents are clustered west of 29th Avenue.

In Census tract 8900, pictured above, white households -- clustered on the east side -- earned an average of $135,250 annually. Black households, clustered on the west, earned less than a third of that total. Yet the area is also considered one of the most diverse in Seattle.

A steep north-south ridge that can't be crossed by foot divides the tract. More than 78 percent of black residents life on the west side of the ridge, where most homes are run down and few new homes exist, the researchers found.

"We're really seeing how environment plays a huge role in the ability to allow groups to separate and to keep integration from actually happening," Gabriel says.

Lest anyone think the phenomenon is unique to Seattle, the team did a separate version of the study focused on Austin and found similar patterns. Areas that seemed diverse often had high degrees of racial separation.

The takeaway, Thomas and Gabriel say, is clear: it may be time to rethink how neighborhoods (and more specifically Census tracts) are defined. In many cases, residents of the same tract don't have shared experiences.

"I bet if you went on the street and asked 1,000 people what their Census tract boundaries are, none of them would know," Gabriel says. "Originally, they were supposed to kind of make sense and fall along major streets. "But as far as how people conceive of their own social space, it doesn't do that."

Their work challenges the idea of what, exactly, it means for an area to be "diverse." In the places Gabriel and Thomas examined, the label often described a statistical measurement of an arbitrarily defined area more than everyday life.

"The holy grail of desegregation is integration and the assumption that everybody should be interacting with each other," Thomas says. "We're finding evidence they aren't. We need to challenge these ideas."

Meanwhile, researchers at Ohio State University and Rutgers University have found a way to examine a similar trend using different data.

They used survey data from Los Angeles that asked residents where they perform daily activities like going to work, shopping at the grocery store, or attending doctors appointments. That information was used to calculate the likelihood that residents of different socioeconomic status living in the same area would come into contact with each other.

It's a more meaningful way to consider whether an area is truly integrated or just appears to have residents of different races and socioeconomic status living in proximity to each other, says Christopher Browning, a sociology professor at Ohio State University.

Like the Washington researchers, he sees a problem with relying on Census data to measure diversity or integration.

For decades, he says, researchers and public policy leaders have looked at Census data and assumed that if an area has many different types of people living with it, they must be interacting with each other.

"We wanted to interrogate that," Browning says.

His study found that as residents' socioeconomic status rises, their likelihood of running into other neighbors - of any socioeconomic status - declines. The pattern is most pronounced in areas with high levels of inequality.

"There's often an assumption that if you bring people into proximity they'll encounter one another," Browning says. "But that hasn't really been tested well."

The implications of those findings could be significant, especially as governments encourage mixed-income housing. Browning says his intention isn't to advocate against those policies. But they may warrant more research, since his data would suggest mixed-income housing doesn't necessarily encourage people different socioeconomic status to interact.

He also emphasized there may be other benefits to mixed-income housing - like giving people with lower socioeconomic status access to better amenities - even if it doesn't promote social interaction. "Maybe we actually don't need social mixing, we just need them to be residing in these better neighborhoods and they'll benefit from larger spill-over effects," Browning says.

Gabriel, of Washington, says his study's findings raise implications for urban planners. Some zoning policies, for example, may help foster segregation, Gabriel says.

In parts of Seattle with large concentrations of blacks and Asian-Americans, Gabriel says, zoning ordinances tend to allow multi-family housing. Desirable locations near the waterfront, however, are often zoned for single-family homes.

"Knowing that there's economic stratification between racial groups, that's a key level of policy that allows racial segregation to happen without appearing racist," Gabriel says.

"The language of segregation has transferred from the overt to the covert," he continued. "Public policy needs to become more sensitive to this type of language that's veiled in economic and political choice but is really rooted in racial segregation."