When we think about the ways immigrants strive to integrate into society, we tend to think of people entering the workforce, studying to improve their English, and engaging in various social institutions.

That integration process is usually considered beneficial for both immigrants and their children.

But a new report from the National Academy of Sciences suggests that immigrant integration is a more complex process that doesn’t always lead to greater forms of wellbeing. And just as we rethink the ramifications of integration, it’s also important to consider the role that immigrants’ host communities play in that process.

Integration revisited

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the 1965 Hart Celler Act, which abolished our nation’s racist quota system for immigrants and ushered in a new era of migration from all over the world. The law replaced the previous policy, which essentially banned Asian and African immigrants and discriminated against specific European nationals, with a more egalitarian, ethnic-blind criteria based on kinship and job skills.

Today, there are about 42 million immigrants living in the United States. Immigrants and their children represent more than a quarter of the U.S. population (2014 ACS 1-Year Estimates; Pew Research Center 2015). America truly is a dynamic nation of all peoples, as shifting flows and patterns have direct effects on racial, religious, and other forms of national diversity.

The NAS report reveals that the relationship between an immigrant’s degree of integration and his or her wellbeing is not so straightforward. By some measures, as immigrants integrate, their wellbeing does improve – most notably measured by subsequent generations achieving higher levels of education and greater annual earnings.

But integration into our society doesn’t improve other measures of wellbeing. For example, the NAS report shows that immigrants, on average, arrive to the United States with better health than the American-born population. Immigrants are less likely to be obese or die from cancer, and they have lower infant mortality rates than native-born Americans. Immigrants also have longer life expectancies, on average, than people born in the U.S.

However, over time, immigrants’ health and the health of their children tend to worsen and become more similar to the health of native-born Americans. That finding undermines the notion that integration leads to an improvement of all forms of wellbeing. Instead, as immigrants integrate, they wind up being affected by both the good and bad sides of living in the U.S.

Community acceptance in Houston

About 1.2 million residents of Harris County, which contains Houston, are foreign-born. They comprise 26 percent of the county’s total population, based on the American Community Survey’s most recent estimates. Of those immigrants, about two-thirds are Hispanic or Latino.

“Integration is a twofold process that depends on the participation of immigrants and their descendants in major social institutions such as schools and the labor market, as well as their social acceptance by other Americans,” said Mary Waters, a Harvard sociologist who chaired the committee that authored the NAS report.

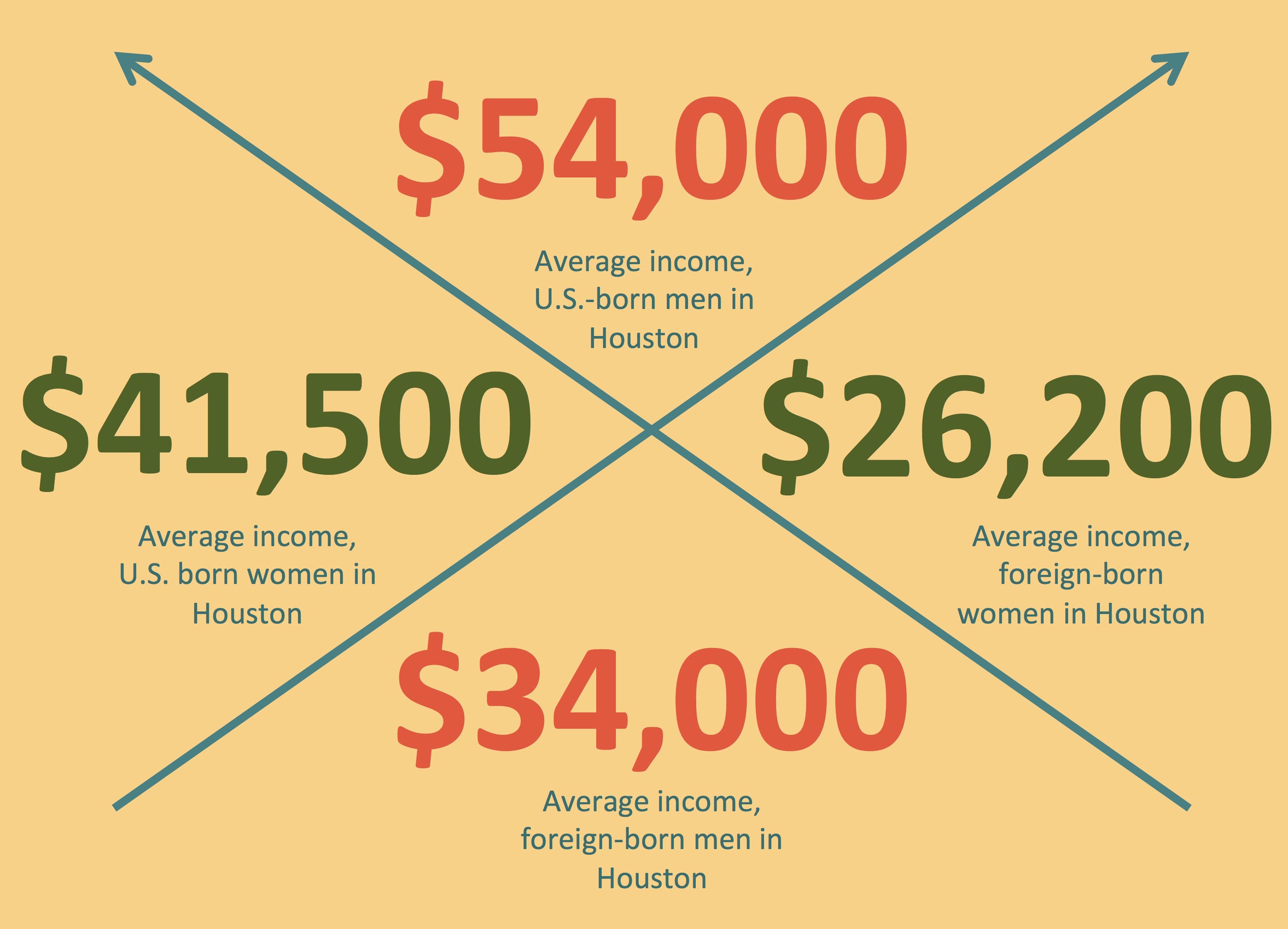

In terms of labor market participation, by a margin of 71 percent to 67 percent, immigrants are more likely than American-born residents to be in the labor force. However, there are striking inequalities in occupations and earnings.

Whereas 40 percent of U.S.-born Houstonians are in the management, business and science fields, only 24 percent of foreign-born Houstonians occupy those jobs. On the other hand, 21 percent of U.S.-born Houstonians are in the service, construction, or maintenance, compared to nearly half of the foreign-born population.

Unsurprisingly, this translates to stark differences in average earnings, illustrated below.

As Waters notes, another aspect worth examining is the other side of the integration process: the communities that receive immigrants.

In other words, integration isn’t just about immigrants. It’s also about the extent to which the communities where immigrants make their homes are willing to accept them.

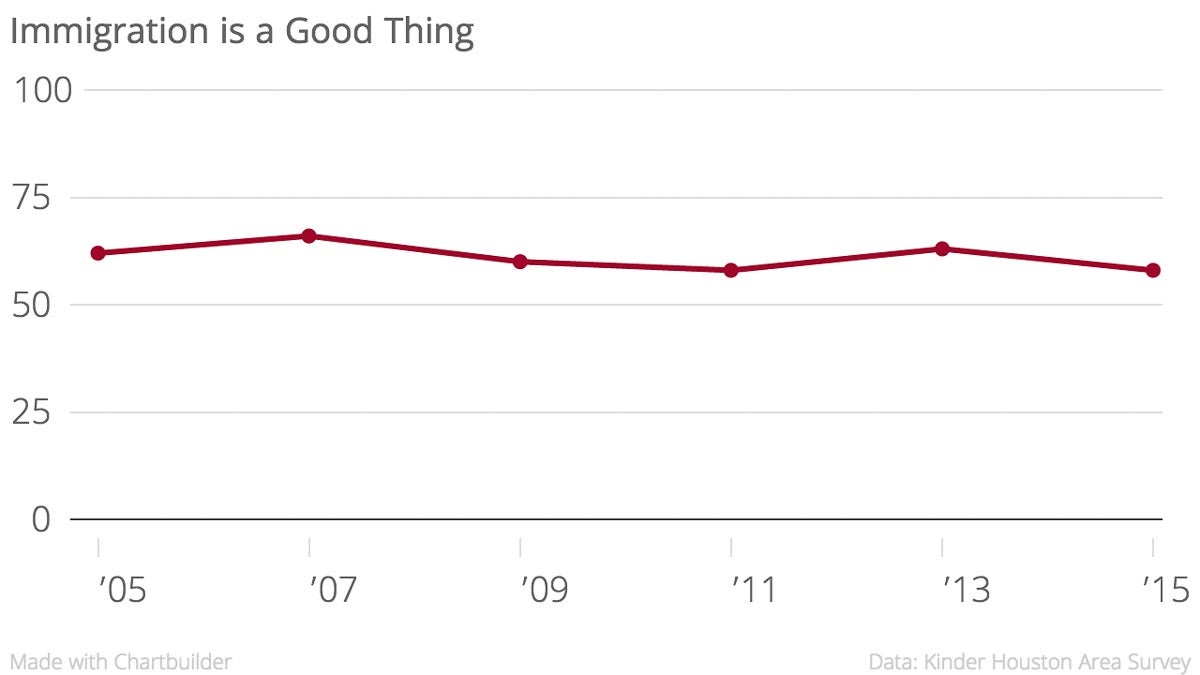

Using data from the Kinder Houston Area Survey, we can see exactly how Houston is doing on that measure.

Over the past 10 years, Houston-area respondents have been asked whether they think the increased diversity in Houston due to immigration is a good thing or a bad thing. In 2005, 62 percent of American-born Houstonians said it was a good thing, and that rate hasn’t changed significantly over the last decade.

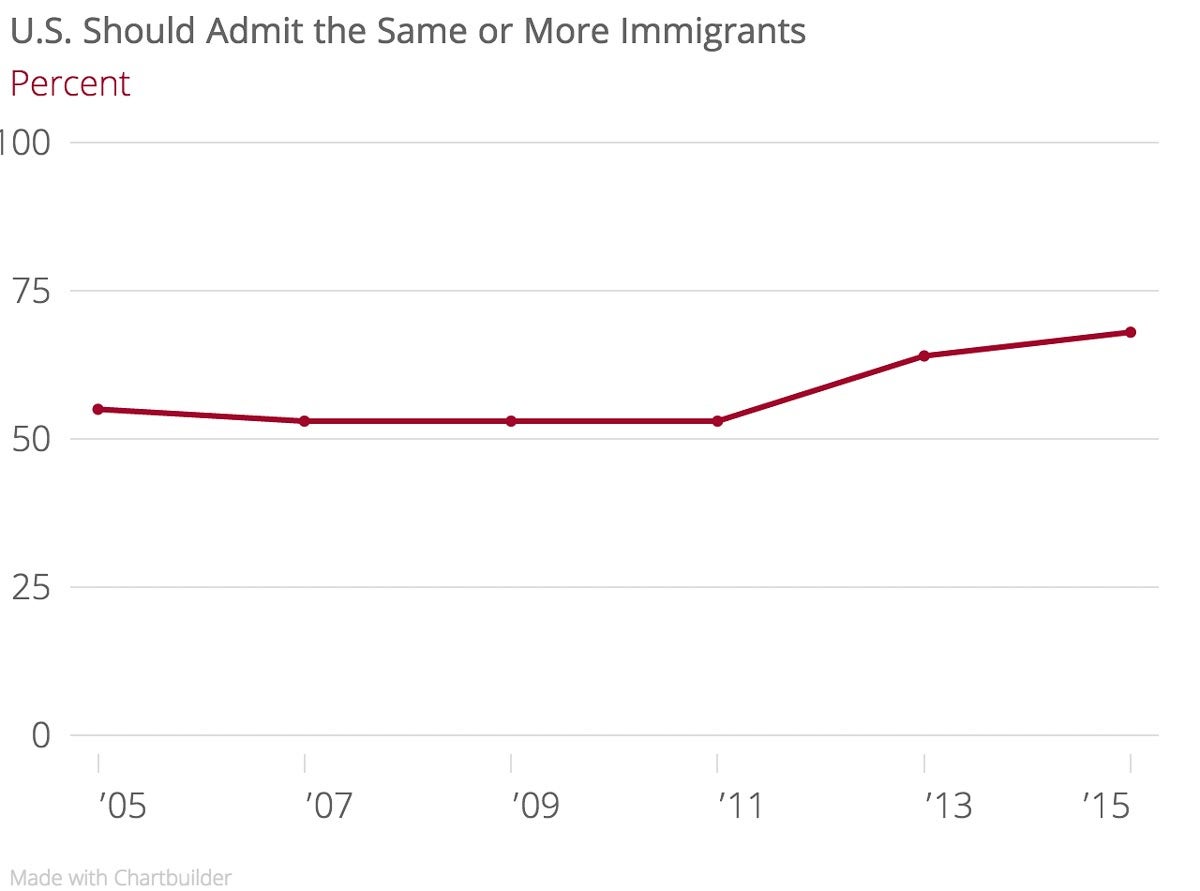

Meanwhile, the percentage of American-born Houstonians who believe the United States should continue to admit the same number of immigrants or more has slowly increased, peaking at more than 66 percent in the 2015 survey.

The Pew Research Center’s latest report finds that 49 percent of Americans believe the U.S. should reduce the number of immigrants it allows to enter the country. In our survey of Harris County residents, we ask a similar question and see significantly different results: only 32 percent said they want to see immigration numbers reduced.

As more immigrants settle in the greater Houston area, their integration will be vital to the future success of Houston. Just as Houston offers immigrants opportunities to better their lives, immigrants and their children contribute to the economic strength and cultural liveliness of this city.

The data suggest Houstonians are relatively more welcoming of immigrants than the country at-large. But there is work to be done on both ends of the integration process.

Improving access to education, healthcare, and well-paying jobs is vital successful integration of immigrants into the social fabric of Houston and the rest of the country. Put simply: our collective future depends on it.