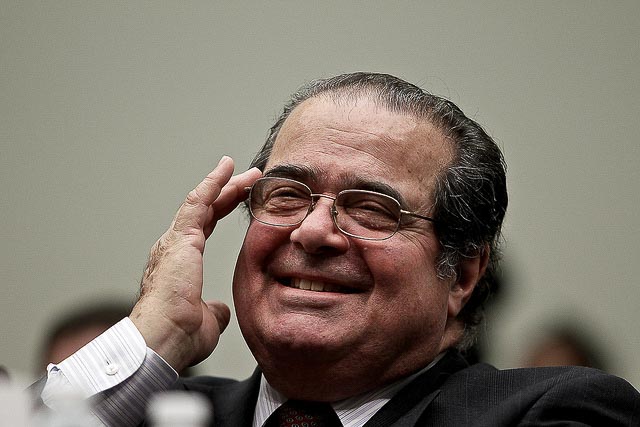

Thirty years ago, in his first big majority opinion -- a land-use case from the California coast -- Antonin Scalia found the colorful and irreverent style that came to distinguish his career on the Supreme Court. And with one clean swipe, he knocked William Brennan out of the box and became the intellectual leader of the court.

Well, I for one am sorry to see Nino go. We go way back together – all the way back to Justice Scalia’s very first term on the court, when he provided CP&DR with great copy for the first big story we ever covered.

But it wasn’t just our first big story. It was the case where Nino found his voice. And it marked the beginning of one of the most momentous shifts in modern legal history: When Scalia began to replace William Brennan as the intellectual leader of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Nollan v. California Coastal Commission, 483 U.S. 825, was one of two land-use cases issued by the U.S. Supreme Court one June day in 1987 that is now remembered as a turning point in the history of property rights. Nollan is often overshadowed by the other case decided that day: First English Evangelical Church of Glendale v. County of Los Angeles ,82 U.S. 304. But in the long run, Nollan has had far more practical significance. And, boy, was that opinion fun to read.

All through the 1970s and '80s, local governments ramped up their land-use regulations against developers, raising the question of when such regulation becomes a "taking" of property. And especially in California after Proposition 13 limited their property tax revenue, government agencies began requiring "exactions" -- conveyance of land, infrastructure money, or easements in exchange for permits -- thereby raising the question of whether an exaction might also be a taking of property. The Supreme Court had danced around especially the first question for years -- but Chief Justice Warren Burger's retirement in 1986 had allowed President Ronald Reagan to reshape the court, elevating William Rehnquist to Chief Justice and adding Scalia as an Associate Justice.

First English finally established that a property owner who suffers from a regulatory taking of property is entitled to monetary compensation. This was considered the more important issue and it included some novel legal thinking. The sober Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote the opinion.

Nollan, by contrast, seemed like one of those crazy one-off California land-use cases that nobody would care about east of Pacific Coast Highway. But, partly thanks to Scalia, it turned out to be far more important in the end.

A family near Ventura wanted to expand their beach shack into a two-story home. As a condition of approval, the Coastal Commission required that the Nollan family to provide an easement across the sand in front of their house so that people could legally walk in front of the house. It was a standard condition that the Coastal Commission slapped on everybody in those days.

But James Nollan was a deputy city attorney in Los Angeles and he sued, saying that there was no relationship between the impact on the public created by the two-story home and the Coastal Commission’s exaction involving the easement across the front of the property.

In what was pretty clearly a post-hoc rationalization, the Coastal Commission’s lawyers said that the two-story house created a psychological barrier between PCH and the beach, a problem that could be mitigated by created a legal easement running along the beach between two nearby beachfront parks. Lower courts had upheld the decision, in large part because California law at the time said that only an indirect relationship between the problem and the exaction was good enough.

And in an opinion that was clearly written to serve as the majority opinion, Brennan – like Scalia now, at the time an 80-year-old intellectual leader with 30 years on the court – wrote that the government deserved great deference in deciding how to ameliorate the problem the Coastal Commission had identified. He said regulation should be shaped “in the context of the overall balance of competing uses of the shoreline.”

Brennan (who sided with the majority in the First English case on the same day) had built majority opinions around his reasoning for decades and clearly expected to do the same in Nollan. But this was the first time he had to contend with Scalia, who had joined the court the previous fall (at about the same time that we were founding CP&DR). This was Scalia’s first big opinion. And Nino was ready for his closeup.

“The lack of nexus between the condition and the original purpose of the building restriction converts that purpose to something other than what it was,” he wrote. “Unless the permit condition serves the same governmental purpose as the development ban, the building restriction is not a valid regulation of land use but an out-and-out plan of extortion".

Developers had been calling California’s aggressive exactions “extortion” for years. Now a U.S. Supreme Court justice was saying it too. And he brought with him not just Rehnquist but also Lewis Powell, Kennedy appointee Byron White, and the well-known moderate Sandra Day O’Connor – creating a five-justice majority.

But Scalia didn’t stop there. Throughout the opinion, he couldn’t resist showing off the operatic range that would characterize his work over the years. He also wrote that “when that essential nexus is eliminated, the situation becames the same as if California law forbade shouting fire in a crowded theater, but granted dispensations to those willing to contribute $100 to the state treasury.”

My personal favorite passage came when Scalia speculated as to what would be an acceptable exaction – something he didn’t have to do but apparently couldn’t resist. An exaction would be acceptable, he said, if it ameliorated the basic problem identified by the Coastal Commission, which in this case was the fact that the two-story house blocked the ocean from the public traveling on PCH. He concluded: “[T] he condition would be constitutional even if it consisted of the requirement that the Nollans provide a viewing spot on their property for passersby with whose sighting of the ocean their new house would interfere.”

As I have often said over the years, it’s hard to imagine that Scalia actually would have upheld that exaction if the Coastal Commission had imposed it. He probably would have found some other reason to strike it down. But the point was made: Ever after, an exaction required a “direct nexus” to be legal.

Brennan was not happy. In his dissent, he wrote that Scalia’s majority opinion “overrul[ed] an eminently reasonable exercise of an expert state agency’s judgment, substituting its own narrow view of how this balance should be struck.” Which, come to think of it, has pretty much been the liberal critique of Scalia ever since. In any event, Brennan had good reason to be mad: He had just been replaced as the intellectual leader of the Supreme Court. Three years later, he retired.

Over time, Rehnquist’s ruling in First English has not proven nearly as consequential as everybody thought it would be at the time. It’s almost impossible to prove when a regulatory taking has actually occurred as a result of delay or repeated rejection of development applications and only a few developers have ever received compensation.

The whole exactions thing, however, was changed forever. Scalia’s opinion hastened the passage of AB 1600, California’s first law requiring accountability for impact fees. Nollan led to Rehnquist’s ruling in Dolan v. City of Tigard, 512 U.S. 374 (1994), which established the “rough proportionality” requirement for exactions, creating the whole Nollan/Dolan doctrine. It formed much of the basis for the California Supreme Court’s ruling in Ehrlich v. City of Culver City, 12 Cal.4th 854 (1996), which solidified California case law around the Nollan/Dolan doctrine.

And eventually Scalia returned to the stage with a bizarre ruling in the complicated Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council case, 505 U.S. 1003 (1992). In a case involving a property owner who was blocked from constructing on his property by state regulations, the Supreme Court ruled that a landowner denied all “economically beneficial or productive” use of his land is entitled to compensation, unless an argument for the regulation could be found in common law.

Lucas was indicative of how Scalia was evolving. No longer was a direct connection to legitimate public policy sufficient to uphold an extremely restrictive land-use regulation; now a basis had to be found in common law, the unwritten laws that emerged in England through the decades and migrated to the United States prior to the constitution. (Scalia often relied on common law, including in his famous and controversial ruling on handguns in 2008.) There was almost nothing, in Scalia’s view, that justified a complete prohibition on developing a piece of property. Though I think it's fair to say that even Scalia had a hard time figuring out how to deal with a nuclear power plant through common law -- a problem he and others have often faced in reaching deep into the legal past to try to wrestle with modern problems.

But that was Scalia. For me as an analyst of land-use law, there will never been a more beautiful moment than that day in June of 1987 when I sat in my home office in Ventura – not 15 miles from the Nollans’ house – reading the Nollan opinion and imagining how wonderful it would be to be able to pay $100 to the government for the privilege of yelling fire in a crowded theater. Thanks for everything, Nino. I’m gonna miss you a lot.