On Tuesday evening, residents and planner types crowded into the cafeteria of Carver High School to discuss the future of the northwest Acres Home neighborhood. Or the future of Acres Homes. Or even Acreage Homes, depending who you ask. The gathering was the latest in a series of meetings as part of the mayor’s Complete Communities initiative meant to direct and coordinate investment for five pilot neighborhoods neglected by the city for decades. To advertise for those meetings, the city’s planning department decided to use Acres Home after talking with community members, raising related questions about neighborhood identity, its history and future.

“Senior Planner Christa Stoneham spoke with community leaders at the start of the Complete Communities process to better understand the history of the community’s name,” according to Anna Sedillo, the department’s communications coordinator, who said someone’s age and tenure in the neighborhood often affects which name they use.

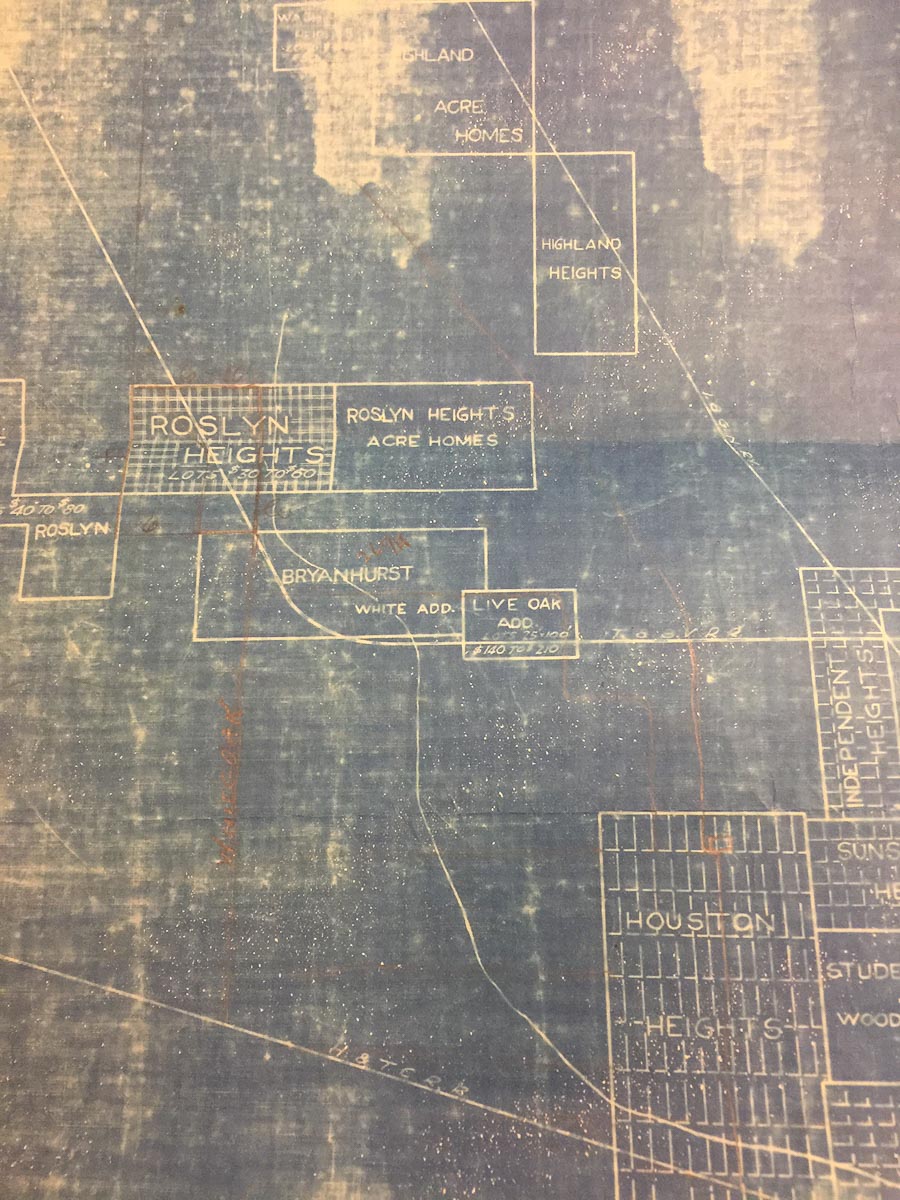

“The community began as Acreage Homes, then Acres Homes, and eventually Acres Home,” according to Sedillo, starting with the development of several subdivisions in the early 1900s by the Wright Land Company and W.W. Mount. Some early subdivision maps even list the different developments using Acre Homes, including Roslyn Heights Acre Homes and Highland Acre Homes. The lots were famously sold by the acre and the subdivisions and larger neighborhood still refer to that history.

Source: Houston Public Library.

Today, while many residents have their preference, the neighborhood’s name seems fluid in the official record. There’s the City of Houston’s Acres Homes Multi-Service Center and Harris County’s Acres Home Health Center. And there’s more, says Cedilla; “...the community is referenced as Acres Home in the Acres Home 1999 Strategic Plan, Acres Home Super Neighborhood 6, and the Acres Home Chamber for Business and Economic Development.” But she added, “it’s also referenced as Acres Homes on the Texas Historical Commission - Acres Homes Community Historical marker and the Beulah Shepard - Acres Homes Neighborhood Library.”

Several city planning documents over the year cite a paper from James L. Marshall, Jr. who penned “Acres Homes - A Proposal” back in 1967. In it he described the area as “the largest unincorporated black community in the South” and documented the agrarian lifestyle it offered residents. That lifestyle is still very much part of the neighborhood, which Susan Rogers and Rafeal Longoria included as part of Houston’s “rurban horseshoe” of African American neighborhoods that formed on the fringes of the city during the 20th century. The City of Houston annexed the neighborhood in chunks over several years, starting in 1958 and ending in 1974, according to document’s from the city’s planning department.

News articles over the years also shifted back and forth between the two names, sometimes even in a single article. And the local paper, It’s About Time, dubbed itself the “Acreage Homes Newspaper.”

In a 1964 Houston Chronicle article, Mayor Louie Welch insisted Acres Homes must be “dealt with” and pondered whether federal anti-poverty dollars could be used in the neighborhood. Some of those dollars would later help the city annex more of the neighborhood.

But the wealth of local organizations over the years shows the neighborhood’s long history of providing for itself as well as identifying itself, including the Acres Homes Transit Company established in the late 1950s, the Acres Homes Volunteer Firefighters Department active in the 1960s and the Acres Homes Beautification Organization founded in 1981 by Edna Washington. The Acres Homes War on Drugs Committee also received federal recognition from President George Bush’s Thousand Points of Light.

Though, as Sedillo noted, the 1999 plan referred to it as Acres Home, as recently as 2006, the city used Acres Homes to identify it as part of the Project Houston Hope initiative, meant to develop affordable housing in six neighborhoods.

One of the many plans created by the city for Acres Homes over the years

Source: Houston Public Library.

At one point, said one 36-year old lifelong resident who asked to remain anonymous, “they had two, three different signs up.” He said he’s heard all the variations over the years but said, “I guess unconsciously everybody says it Acres Homes.”

Toshia Hurd, who runs her own Toshia Hurd Foundation and is also a lifelong resident of the neighborhood, agreed; “We say Acres Homes with an s.” At 35, Hurd said Acreage Homes was also common among older residents in particular. “Some people put an ‘s’ on it and some people don’t. That’s how we know if you’re from here,” she added.

Though there’s been slippage throughout the years, the current divide points to another conversation about the transformation underway in the historically African American neighborhood.

Ernest Busby, 75, is originally from Fifth Ward but moved to the neighborhood he knows as Acreage Homes 10 years ago for the seclusion, peace and good neighbors. But in that time, he's seen signs of change, noting an influx of white residents. He seems nonplussed by the shift but says, “there’s always lost history when the culture changes.”

Part of that history could be the way the neighborhood identifies.

A 2016 study of a gentrifying neighborhood in Philadelphia found that white and non-white residents identified both the geographic boundaries and name of the same neighborhood differently. The study, by Harvard University’s Jackelyn Hwang, also found in interviews with 56 residents, that non-white residents tended to define the boundaries of their neighborhood as larger than the white residents, who identified with smaller subdivisions within the neighborhood. “The internal narratives of neighborhood identity and boundaries are not only embedded within a broader context of inequality but also shape how neighborhood identities and boundaries remain the same or change,” writes Hwang.

Another 2017 study by David J. Madden of the London School of Economics also found that place names can capture important structural divides within transforming neighborhoods. “Real estate developers and residents of expensive private housing use toponymy to legitimise their privileged positions, while public housing residents experience the same toponymic change as a form of symbolic displacement,” he writes.

The 36-year old small business owner said he sees those tensions in the current conversation about the neighborhood. “Acres Homes has been under development for a while,” he said, “and it’s not for the original people of Acres Homes, so you have people like me making sure it is.”

That matters more to him than the name, he said. “It doesn’t matter what it’s called, it’s the people that make it up that make ” It isn’t as if Acres Home is a new invention in the way place names in other neighborhoods are largely fabrications of the real estate industry, as the record shows. But to him it’s akin to what he said has happened in nearby Independence Heights. Though that is its historical name, he knew it always as Studewood and said he felt the shift back to Independence Heights is at least partly a reflection of its recent redevelopment.

The small business owner said he signed up for every single task force under the Complete Communities effort, from infrastructure to neighborhood character to ensure the longtime residents of Acres Homes reap the benefits of investment, regardless of the name. “You can't have education without mental health and you can’t have mental health without infrastructure,” he explained.

But, argues Hwang, a name can be part of that equation. “How residents define their neighborhoods can have tangible consequences for access to resources and opportunities,” she writes. “If institutions that serve as political resources legitimate some residents’ neighborhood definitions and their neighborhood membership and not others, some organizations may garner more resources than others when organizations associated with each defined neighborhood compete for limited resources.”

Hurd is also hopeful about the Complete Communities effort despite a history of such planning efforts that often fell short of expectations. “This seems like the first one where they really engaged the community,” she said, perhaps because the mayor himself claims one of the five neighborhoods as home.

So what does he call home? In Sylvester Turner’s official biography, the City calls it Acres Homes. And his campaign website declared, “We Started in Acres Homes.” But in a statement from his press office, Turner said, “Technically the correct name is Acreage Home. Many of us say Acres Home. And then for those of us who are indigenous to the area, so to speak, we say, the 4-4.”

Regardless, said Hurd, “I think he’s trying to give us a seat at the table.”

And the residents aren’t going to squander the opportunity, no matter the name on the flyers advertising for upcoming meetings.

“I don’t even have the name tattooed on me,” said the small business owner. Instead he’s got 44, the call sign of the neighborhood that refers to the Metro bus route that serves the area. “Worldwide,” he said, “everybody knows” that number means Acres Homes.

Plus, he said, “Whoever comes in the next five years, ain’t no telling what they’re going to call it.”