Editor’s note: This is part one of an essay from Kinder Institute Director Bill Fulton in which he revisits the urban renewal of his hometown, Auburn, New York, in the 1970s, and the ways it changed both him and the city he loved when he was growing up. The second part will run on Thursday, Nov. 12.

One warm summer’s day in 1974, when I was a college kid interning as a cub reporter at what was then known as the Auburn Citizen-Advertiser, I left the paper’s new building on Dill Street in downtown Auburn, New York, and walked three blocks to the City Hall on South Street to cover a meeting of the City Council — or, to be technically accurate, the Auburn Urban Renewal Agency, or AURA, which was an offshoot of the council.

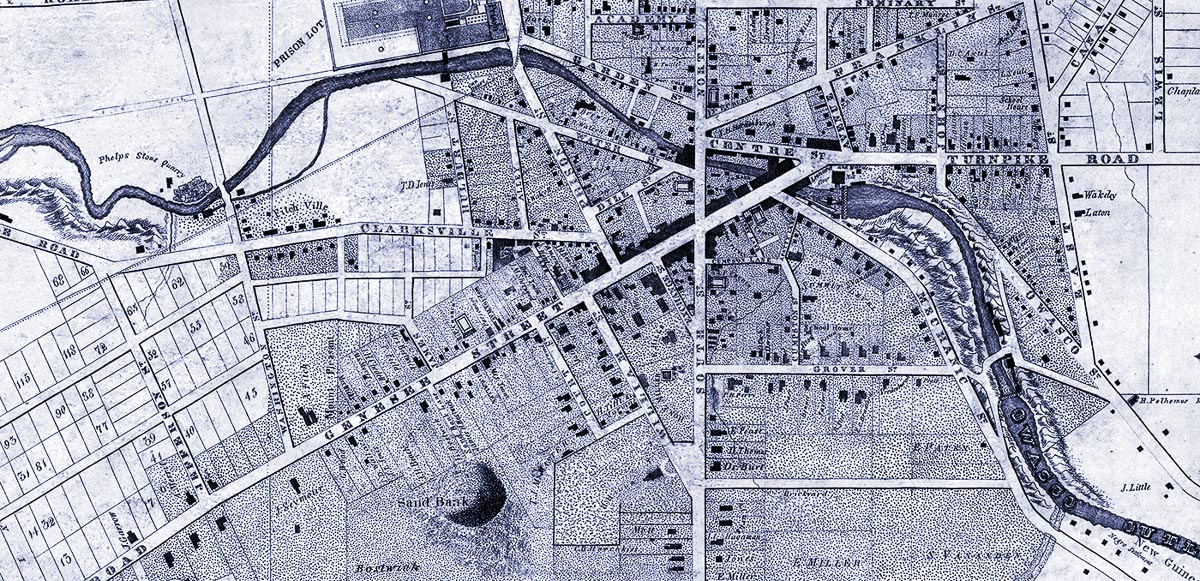

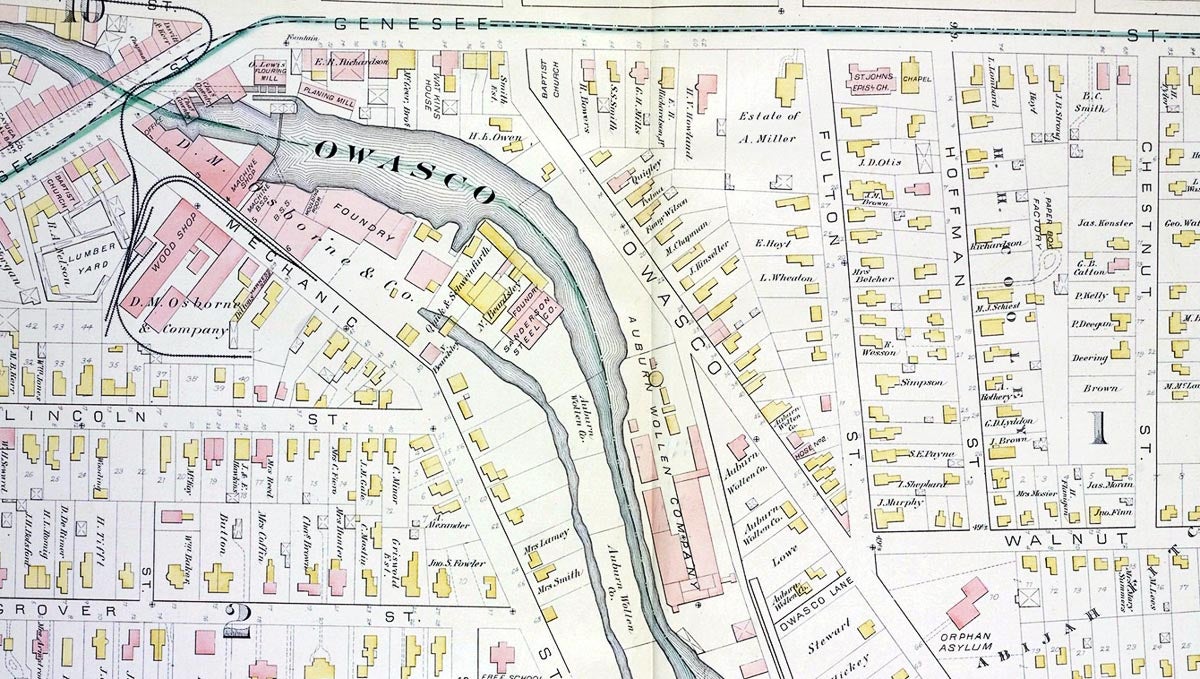

In my recollection, it was like traversing a war zone. As I walked down Dill Street to North Street, on my left a new arterial road — the Auburn Arterial — was being plowed through the middle of long-established neighborhoods I had known my whole life. Ahead of me, along Market Street, buildings dating back to the 19th century were behind demolished with federal urban renewal funds, making way for a new “Loop Road” around downtown and opening up access to the Owasco River (which in those days we called “the Outlet”) for the first time in a century. And, as I crossed Genesee Street, where North and South Streets met — downtown Auburn’s “100% corner” — the main street was torn up as the city began a 16-year effort to separate the sanitary sewer and the storm sewer.

Although I was only 18 at the time, the city I had known all my life — the only city I had ever known — was disappearing before my very eyes.

When I got to City Hall and the City Council emerged into the council chambers from an anteroom, I was in awe — especially of Auburn’s legendary mayor, Paul Lattimore. It was the first time I had ever covered the City Council and it was a heady experience. Even at that young age, I somehow understood how power in a city worked and I knew I was in the presence of it. At a time when Auburn’s factories were closing or moving South — just as they were all across the northern industrial belt — Lattimore had recently gained national publicity by persuading two Japanese companies to open a new steel mill in town. And it was clear that all of the city-changing activity I had witnessed on my stroll over to City Hall had resulted from decisions made in this room.

The press table, where I was sitting, was located not in front of the dais but to the side, providing me a view of Lattimore that was unobscured by the dais. After he sat down he hiked his pants up to the knees, revealing his legs to me (and because of the dais, only me). I later realized this was his habit during council meetings. The group met briefly as the City Council, then reconvened as the board of the Auburn Urban Renewal Agency to discuss the notorious Parcel 21.

Parcel 21 was a large, now-vacant property at the corner of Genesee and Osborne streets, almost directly across from City Hall. Only a few years before, part of it had housed the Palace Theater, a movie theater dating back to World War I. For much of Auburn’s history, most of the parcel had been home to the city’s most important factory, the Osborne Works, which manufactured agricultural combines starting around the time of the Civil War. The Osborne Works had long ago been sold to International Harvester and moved out of town, and five years earlier some of the old buildings had burned down. Subsequently, the urban renewal agency had condemned all the properties, assembled a large lot, and torn the remaining buildings down. (Fires were a constant problem in Auburn, and urban renewal was in part an effort to get ahead of the arson curve.)

As I sat at the press table looking at Lattimore’s bare legs and watching the Council operate, I realized two things. First, in those days, before open-meetings laws, most of the topics on the agenda had already been discussed in detail behind closed doors in the anteroom. Second — and even more alarming — it was clear that, to the Council’s surprise, the city couldn’t find a developer interested in Parcel 21, in spite of the fact that the councilors clearly viewed it as the most attractive downtown site that urban renewal had created.

Eventually, after several visits to Rochester, the city persuaded a regional grocery chain to relocate its stores from a suburban shopping center on the outskirts of the city to Parcel 21. The market was nobody’s idea of great urban design — it faced a giant parking lot and presented a blank wall to Genesee Street — but it was better than nothing. And close to half a century later, the Wegman’s is viewed as the heart and soul of downtown.

Because it was the first City Council meeting I ever attended — and because it dealt with the first urban development challenge I had ever learned about — that meeting in the summer of ’74 is seared in my memory. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was my first experience at the intersection of journalism and urban planning — the two professions that would define my life. And it would be many, many years before I understood how Auburn and its history — especially the scars left on the city by urban renewal in the 1970s — had shaped my understanding of cities and, indeed, my entire career.

It is hard for anybody who grew up in America in the past half-century to understand how self-contained — how totally complete — towns like Auburn were. And not just in the 19th century or during World War I, but as recently as the 1960s and ‘70s.

In my memory, Auburn — then a city with just over 30,000 people — had four banks, at least three jewelers, two meat markets, two mainstream department stores and a high-end boutique department store, two movie theaters, two or three hotels, a local newspaper and radio station, several car dealerships, a sporting equipment store, a music store, a YMCA, a museum that had once been the home of William Seward (Lincoln’s secretary of state, played by David Strathairn in the recent movie), a handsome building housing the police and fire departments, an iconic post office that looked like a castle, an iconic diner, innumerable restaurants and bars, a high school and, believe it not, a maximum-security state prison that had been built by the inmates in 1820. Remarkably enough, all these businesses and institutions were concentrated in a downtown barely six blocks long and three blocks wide.

The downtown was also home to the City Hall and the County Courthouse, as well as a lively cadre of lawyers and political operatives that revolved around them. Several churches and other civic institutions, such as the local library and a historic cemetery, were situated on the edge of downtown, within easy walking distance. I never recall going to a doctor’s office that was not downtown. My family lived in a handsome 1920s doctor/lawyer/merchant neighborhood — one mile from downtown.

Elsewhere in the town — which was only two miles long and three miles wide — ethnic neighborhoods clustered around factories, each neighborhood featuring its own shopping district, bars and restaurants, and social clubs. Even into the ’70s, these ethnic neighborhoods held firm, with their local groceries and candy stores and churches, almost all of which were Roman Catholic. Auburn had a popular minor league baseball team (which was and still is the only community-owned, nonprofit team in the country) as well as thriving recreational softball leagues in the summer and bowling leagues in the winter. The entire city was easily walkable, bikeable and busable.

Our family’s entire life revolved around this small city and especially its downtown, where everything we might need was located. There were very few reasons you would ever leave town — or look beyond it for anything that had to do with your day-to-day life. You might go to Syracuse or Rochester for a concert, or occasionally go to a shopping mall in suburban Syracuse, 20 miles away, to get something at a particular store not found in Auburn. Once in a while, if I couldn’t find — or wait for — a book I wanted at our local bookstore, I’d take the bus to Syracuse to get it.

The Fultons had lived in Auburn for more than a hundred years, gradually moving upward from the working class to the middle class. My parents seemed to know everybody. My father had been a rogue school board candidate and my mom was one of the first women on the city parks and recreation commission, where she focused — to everyone’s astonishment — on parks and the civic band rather than on recreational softball, which was viewed by most people as the commission’s most important mission. It wasn’t surprising that they knew everyone, of course: Few families moved in or out of Auburn. The population had stopped growing when immigration shut down in the 1920s and everybody had pretty much stayed put ever since.

For all these reasons, life beyond Auburn didn’t really exist, or so it seemed to me when I was growing up. We’d have dinner on special occasions in the nearby charming villages of Skaneateles and Aurora. We’d occasionally visit relatives in other small upstate towns and once a year we’d go on vacation to the Adirondacks. But other than that, we never traveled anywhere. (Indeed, we seemed glued to Upstate New York: One year when our favorite Adirondack resort was closed, we spent our vacation traveling to see other sights, but they were all in upstate: the St. Lawrence Seaway, Cooperstown, Niagara Falls. We never even went to Pennsylvania.)

Obviously there was a big world out there: I saw it on television and read about it in the three New York newspapers my father bought every day. And, of course, as a manufacturing town, Auburn was connected to the world in ways I didn’t understand — raw materials flowed in from everywhere and finished products flowed out to everywhere. But the outside world didn’t seem real — or, perhaps more accurately, accessible — to me. My favorite athlete was the enthusiastic and graceful Willie Mays, and I spent many an afternoon watching him chase fly balls up against the chain-link center field fence of Candlestick Park on television. But the idea that San Francisco was an actual place in the real world — a place that I could go to, visit and experience — was simply something that never occurred to me, even as a teenager.

In spite of the fact that Auburn was my entire world — or perhaps because of it — I was endlessly fascinated by both its built and natural environment. From the time my parents bought me a two-wheeler for my seventh birthday, I was all over town looking at everything: leftover corner stores in the middle of residential neighborhoods, gullies and culverts that transported water toward the Outlet, the little waterfalls, the handsome Depression-era schools, the fabulous 19th-century mill owners’ mansions along South Street, the railroad tracks, the churches (there were more than 40 of them), the farmland only a few blocks from town and, most of all, The Outlet itself and how it intersected with downtown — the two most prominent features in the city, at least to my mind at the time.

The Outlet was the very reason Auburn existed where it did, because the steep drops in elevation from Owasco Lake northwest toward the Seneca River and Lake Ontario had attracted the first settlers, who operated grist mills. All of the factories were located along the river because they had originally used water power. Even so, the Outlet was almost completely invisible downtown, because so many buildings had been built backing up to it in the 19th century, as was typical everywhere in America. Yet even then, a good portion of the Outlet was open, with woods on either side, so I remember the experience of weaving in and out of natural and built settings all the time as I rode my bike. And in those days, no street in town — not even the main drag, Genesee Street, which doubled U.S. Route 20 — was so intimidating that a 7-year-old on a bicycle was afraid to cross it.

Most of the buildings in town — especially downtown — dated from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and I was fascinated not only with the buildings themselves but also with how they had been imposed on a natural landscape that was almost impossible to find. Both Hogan’s Meat Market and Hunter’s Dinerant were perched on platforms above the Outlet. (Hogan’s is long gone because of urban renewal, but Hunter’s is still there in the location where Auburn was first founded, or was until the COVID-19 crisis, sporting perhaps the most iconic sign in town.) And while the Outlet was hard to find, it wasn’t impossible. If you found your way to the backsides of the old commercial buildings downtown — sometimes by walking around them, sometimes by ducking through a small doorway or driveway — you were in a completely different and fascinating world. Buildings built on stilts. Old loading docks. Rusty porches. At home in my sandbox, I tried to recreate the town and these buildings on a regular basis.

Later on, in high school, when I began to drive and had friends from all over the city — and not just my neighborhood — I got to know the factory-gate neighborhoods that had been settled a half-century before by Poles, Ukrainians and Italians. The families lived in modest but comfortable homes and many of the breadwinners still walked to work, almost literally down the street, in the factories. Of course, the biggest and most important “factory” in town was the prison itself, located along the river less than a half-mile from downtown. It did not seem odd to me at the time that many of the prison guards themselves lived in two-story homes across the street from the prison and its guard towers (on a street called, not surprisingly, Wall Street), nor that when you had dinner at Balloon’s, the wonderful Italian restaurant on Washington Street, you parked against the back wall of the prison, which was across the street.

Many years later, when I was a practicing urban planner, this type of very concentrated urban development came to be known as “smart growth” — “smart” because it was space-efficient, walkable and inexpensive to provide services to, compared to the suburbs — but in those days it was just the way things worked. In fact, the word “growth” never really entered my mind because there wasn’t any. Auburn’s urban patterns as I knew them growing up had been pretty much set by World War I — built on somewhat in the 1920s, but stagnant, of course, during the Depression and World War II. The factories were still mostly thriving in the postwar era, but the population of the city was not growing, so the postwar suburban boom almost bypassed Auburn completely. A few houses were built on the outskirts of town and out on Owasco Lake, but suburban production homebuilding was nonexistent. The 1920s subdivision where I grew up was still being built out in the 1960s — so slowly that I didn’t realize I lived in a subdivision at all.

As it happened, this period of stability coincided with the life span of my parents, both of whom were born around World War I. My father, in particular, had an amazing ability to absorb and understand Auburn’s physical environment and what it meant — an ability he passed on to me, even though I wasn’t consciously aware of it at the time.

My Dad was a salesman and a P.R. guy, so there was no reason to think he had any particular intuition or insight into how cities worked. He grew up on Lawton Avenue in Auburn, behind St. Alphonsus Church, and he always lived — and for most of his life, also worked — no more than a mile from the house he grew up in.

Yet, for some reason, he had an instinctive feel for cities. My mom used to say that they could drive into any town and he could immediately find the downtown and the ballpark. (He also loved trains, and especially the long-gone interurbans, which connected Auburn to Syracuse and Rochester when he was a kid.) He loved all the things that made Auburn distinctive before urban renewal, especially the businesses downtown, like Poolos’s soda fountain, where he had gone as a kid and still bought ribbon candy at Christmas. His uncle, Bill Fulton, had operated a jewelry shop on Genesee Street for decades. Dad had grown up in First Presbyterian Church — the one whose steeple eventually collapsed — just steps from downtown. And he was the kind of guy who always wanted to be in the middle of what was going on in Auburn. I can remember that when the Osborne Mill caught fire in 1969 — helping to create the vacant lot that became Parcel 21 — most people in town got in their cars and drove away from it. Our whole family got in the car and drove toward it. This was going to be an important event that would change the city’s physical environment and my father wanted to witness it.

From Dad I learned one of the most important lessons of my life — one that has always caused me to favor cities and villages over suburbs: As wonderful as your home can be, it is not enough all by itself. You have to look beyond your own home to fulfill yourself on a daily basis. Or, as I have often said over the years, my town is my house.

Dad also understood how the town worked — how things got done — and he understood the relationship between the power structure and the city itself. He knew the mayor and the general manager of the radio station and the prominent merchants and lawyers, but he also knew the cops and the firefighters and the bus drivers, all of whom he had gone to high school with, and he saw how it all fit together. He understood intuitively what I did not understand until I was a reporter — that all that demolition and change I saw on my walk from the Citizen-Advertiser building to City Hall occurred because of the decisions made inside that City Hall, which in turn were influenced by a wide variety of interest groups in town, ranging from the Chamber of Commerce to the police union to the Mafia.

So, it was not surprising that, when the urban renewal reckoning finally came, it broke my father’s heart.

In 1965, a “central business district subcommittee” of the Auburn Planning Board, then led by future Mayor Paul Lattimore, released a study of Downtown Auburn’s conditions. I am in possession of a copy because of an incredible coincidence: Thirty-five years later, when I was living in Ventura, California, I was given a copy by Dick Maggio, planning director of nearby Oxnard, who had worked on the document as a young planner in Auburn.

The report itself makes for sobering reading. While acknowledging that downtown was still the commercial center of Auburn and surrounding Cayuga County, it raised a number of red flags. Downtown’s advantage was already being undermined by strip shopping centers nearby. (The only reason a full-fledged regional mall didn’t exist was that the city hadn’t grown in population since the 1920s. The Planning Board could see that a mall was coming sooner or later — and it did when the notorious Pyramid Co. of Syracuse opened Fingerlakes Mall in 1980.) Even so, there were two lingering problems: Downtown was extremely congested by traffic — only 10 cars at a time could make it through the traffic signal at the main intersection — and the 19th century commercial buildings throughout downtown had long since become obsolete. Something needed to be done.

Thus was born the Auburn Urban Renewal Agency. It wasn’t an unusual move at the time: Backed by federal funds, urban renewal was a trend throughout the country. “Obsolete” buildings and districts were razed all over the country in the name of “slum clearance.” In Auburn, as in many other cities, the goal was not just to remove “slums” but to revitalize a struggling downtown business district by making it more competitive with car-oriented suburban shopping centers. As a result of the 1965 analysis, the Auburn Urban Renewal Agency came up with a huge and daring plan: Tear down half the buildings in the downtown and build a “Loop Road” around the downtown in order to facilitate traffic flow and revitalize commerce. The federal government was happy to give Auburn the money to do this, just as it gave the money to hundreds of cities around the country for similar efforts. And many business owners — already struggling and saddled with 19th century buildings — were happy to get paid off to go out of business.

Of course, at more or less the same time, the State of New York was working on its own plan to clear out the traffic congestion on U.S. 20 (and New York State Route 5) through Downtown Auburn. Several routes were considered, including a route that would have completely bypassed the city. But in typical fashion, many Auburn small-business owners were fearful that they would lose too much business if traffic didn’t go by their stores, and so they lobbied for a route that went through the center of town, just two blocks to the north of Genesee Street.

As a result, in the early 1970s, at the same time that the city was razing half of downtown and building the Loop Road, the state was building the Auburn Arterial just to the north, demolishing 200 structures and eliminating century-old neighborhoods in the process. (Uncharacteristically — but mercifully — the historically Black neighborhood was spared, largely because it was located adjacent to the historic district containing the 19th century mill owners’ mansions south of downtown, away from the through highways.)

The city’s leaders thought they were saving the town.

But they could not have predicted the current they would be swimming against: The 1970s turned out to be the era when factories began to shutter all over Upstate New York and ambitious young people — like me — left for economic opportunity elsewhere. The result was that the Auburn Urban Renewal Agency had set the table for developers to take advantage of a market that no longer existed. For almost a half-century now, Downtown Auburn has existed in a kind of stasis: Half a beautiful historic town, half a wasteland, waiting for the market to return.

By the time the devastation was complete, my father had lived in Auburn for more than 60 years — his entire life except for a short time at college in Michigan. The city defined him, consumed him. He was full of stories about the city and its places — especially the downtown, where virtually all the important experiences of his life had occurred. And yet, after urban renewal and the arterial, when he and my mom retired to the Adirondacks, he never looked back.

It took me a long time — almost 40 years — to realize that I too was heartbroken about what happened to Auburn and that this heartbreak had actually defined my career, both as a journalist and an urban planner. In recent years, I have jokingly referred to my urban PTSD — the trauma I experienced as a high school and college kid watching my beautiful, historic little city half demolished. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that even more than my father, I left Auburn behind for a long time. I moved to Southern California — about as far away from Auburn as you can get and still be in the Continental United States — and didn’t come back much for 20 years.

And on that journey, I kept looking for my Auburn — a place that somehow combined a small scale with the concentrated urbanism that I knew as a kid. But at the time I was looking, it seemed impossible to imagine that this kind of small-town urbanism would ever exist again anywhere in America.

In part two, Fulton leaves Auburn for Los Angeles, “a place where people from all over the country could escape places like Auburn that boxed them in, and build a prosperous, happy and auto-oriented life.” L.A. was also alienating — the opposite of Auburn — and Fulton felt sure he would never experience anything like the walkable, small-scale urbanism he knew as a kid. That is, until he found Ventura.

This essay originally was published on Medium.