Do you trust your neighbors? Do you trust people in your city? Do you trust most people?

That's the question analyzed in recent research from Jie Wu, director of research management at the Kinder Institute, and Kiara Douds, a Kinder Institute scholar and sociology graduate student at New York University. Using data from the 2014 Kinder Houston Area Survey for both Harris and Fort Bend counties - the most populous and diverse in the Houston metropolitan area - the researchers tested the prevailing notion that more racially and ethnically diverse areas have lower generalized trust against the relative segregation found throughout the counties.

Generalized trust, or the general belief that most people in a society are trustworthy, is associated with a host of positive outcomes, including, "economic growth, less government corruption, lower levels of political polarization, more tolerance, wider support for social welfare program, more volunteering," and other benefits. But how that trust is formed and key factors that play into it aren't exactly clear to researchers. Though prior studies have seemed to support the idea that more diversity is actually "bad" for generalized trust, "little research has assessed the effects of segregation on generalized trust," note the authors of the study published online in the journal, Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. Overall, these studies have also shown persistent gaps between black and white respondents, with black respondents expressing lower generalized trust. Hispanic respondents also express lower overall trust than white respondents.

Enter Harris and Fort Bend counties. In 2012, Harris County was 33 percent non-Hispanic white, 19 percent non-Hispanic black, 41 percent Hispanic and 8 percent Asian or some other race, according to Census estimates. Fort Bend, meanwhile, was 36 percent non-Hispanic white, 21 percent non-Hispanic black, 24 percent Hispanic and 19 percent Asian or some other race.

But as the study notes and residents in these counties know, "an area can at once be both diverse and highly segregated if the racial groups live separately from one another." This is very much the case in Houston, where the researchers say Hispanic-white and Asian-white segregation has actually "increased in the past three decades, while black-white segregation has slowly decreased but is still the highest form of segregation in the region."

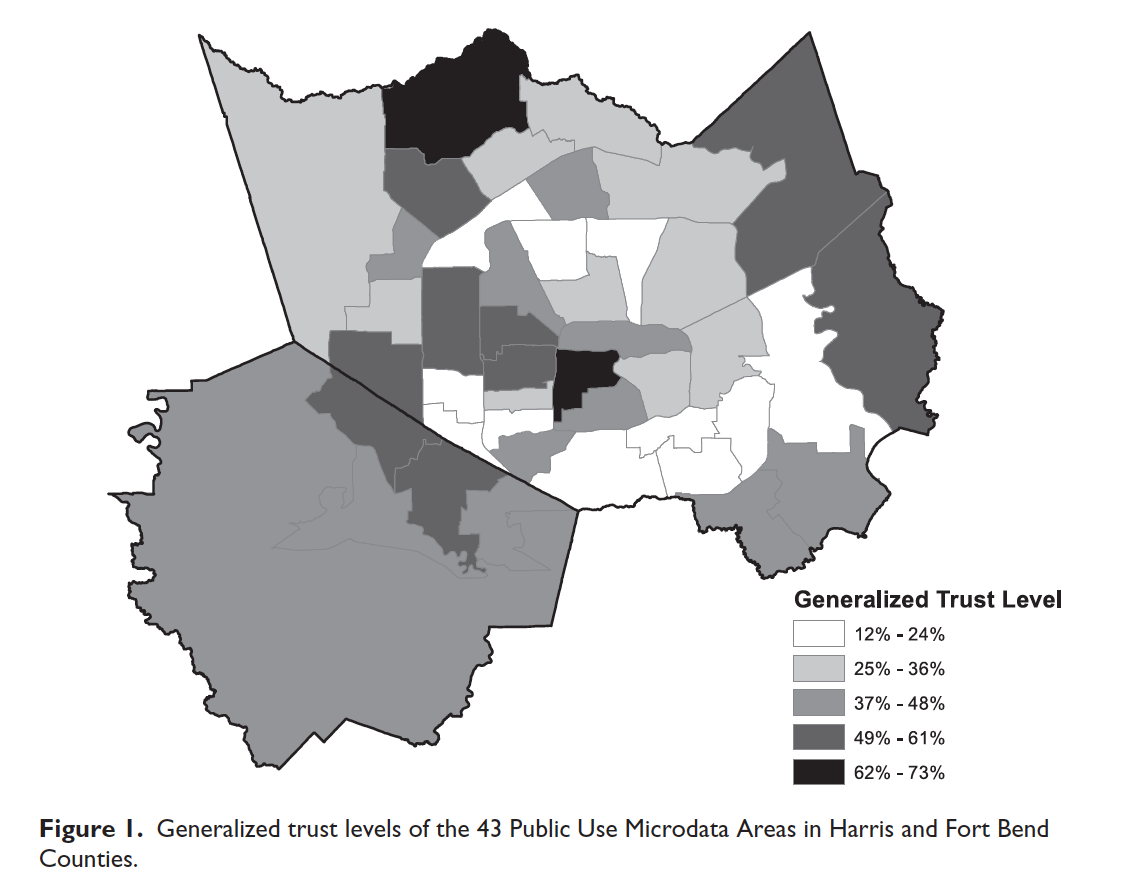

The researchers did not look at segregation at the neighborhood level, but instead used the larger Census unit, the Public Use Microdata Area, arguing that the larger area better captured the segregation Houstonians encountered in their daily lives. Respondents were asked whether they agreed that "most people can be trusted," or, "you can't be too careful in dealing with people." The researchers found a huge spread, with some areas reporting a generalized trust level of just 12 percent while others had trust levels of 73 percent. Because previous research has shown that areas of high-poverty tend to report lower generalized trust, the researchers controlled for some socioeconomic factors.

The findings revealed that overall women tended to be less trusting, as did older individuals as well as people who had been in Houston longer. In addition, the study notes, "blacks and Hispanics have significantly lower odds of being trusting than whites," a measure that, unsurprisingly, correlated directly with how often individuals reported experiencing discrimination. Indeed, an individual's reported experience with racial discrimination was one of the strongest predictors of generalized trust.

Other data from the National Conference on Citizenship puts Houston near the bottom of the list when it comes to trust. The Houston metro area ranked 48 out of 50 for "trusting neighborhoods" based on the results of its 2013 survey.

Interestingly, the researchers also found that generalized trust was higher in racially segregated areas. "The implication we draw from this is not that racial segregation is desirable," the authors conclude, "on the contrary, we take this to mean that in areas in which individuals feel as though they have something in common with those around them, they are more trusting." It comes down to what respondents have in mind what they assess the trustworthiness of "most people," argue the researchers. "If individuals live in isolation from other racial groups, it seems unlikely that these groups would be included in interpretations of most people," the authors argue.

No matter the level of segregation, individuals who said they had a close personal friend who was from a different racial or ethnic background were more likely to report having higher generalized trust, lending support, the researchers write, "to policy efforts to diversify schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces."