But suspending evictions is also the right move for Census 2020. Prior to the public health crisis, our community was gearing up to promote YES! to Census 2020, a locally-made campaign to ensure that everyone in Harris County gets counted. This is one of the most important, once-in-a-decade opportunities to collect important data about our country and our people.

There are many moral, ethical, and business reasons to suspend evictions during this initial suppression period for COVID-19. In this post, we look at how evictions could impact the Census 2020 count, and make the case for extending the suspension of evictions beyond April 19. In fact, we believe that evictions should be paused until the end of the census non-response follow up operation, which ends in late July.

How Evictions Affect a Complete Count

Every ten years, the Census Bureau conducts a nationwide count of every person living within our borders. This count determines political representation, including how many congressional representatives each state gets and how district lines are drawn. It also affects funding allocations for dozens of federal programs, like Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, the National School Lunch Program, and Community Development Block Grant funding. In other words, failing to count everyone would mean that our region leaves millions of dollars in federal funding on the table.

Most people will “self-respond” to the Census, meaning that they voluntarily fill out their census form online, through the mail, or over the phone. For everyone else, the Census Bureau was supposed to hire thousands of census takers to knock on doors and interview people directly. But in response to the public health crisis, they have suspended field operations for at least two weeks. This makes it even more important for households to fill out the form for themselves.

Evictions could harm response rates and make it more difficult to reach people who are not going to self-respond. Already, renters are much less likely to self-respond to the census than homeowners. Evictions mean that the people living in a residential unit on March 1 won’t be living there by the time that the Census tries to count them a few weeks later. It also means that those people will be much harder to count, and might not get counted at all.

Evictions in Harris County

We took a close look at eviction data in Harris County to understand how evictions might impact census outreach efforts. Our main data source is the Harris County Justice of the Peace Court. This data includes eviction filings and disposals, including the address of the defendant, the amount of money at issue, and judgement rendered. For this analysis, we focus on eviction filings, regardless of whether the renter is evicted, to better capture the risk of household mobility associated with the threat of eviction. This does not capture all instances where a landlord issued a Notice to Vacate, so the actual threat of eviction affects more tenants than the data reflects here.

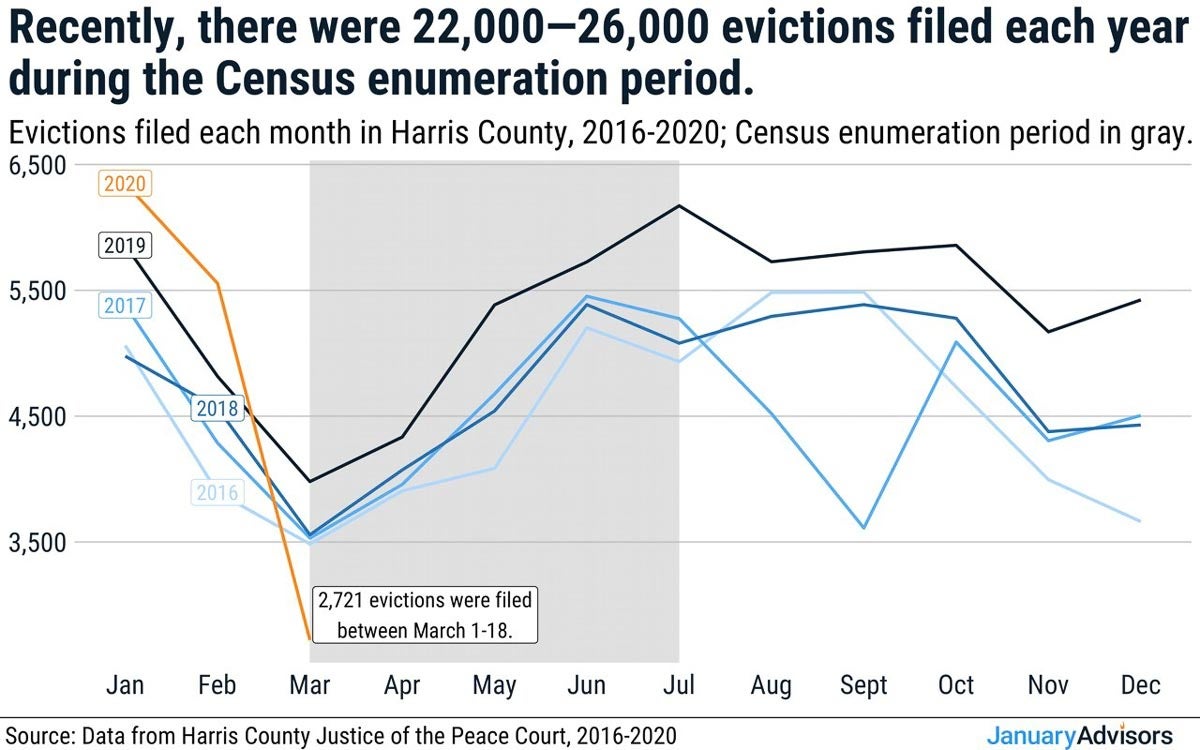

The chart below shows a regular seasonal pattern of eviction filings between March and July over the past four years. Consistently, March has had the lowest number of eviction filings with a steady increase through July. Under normal circumstances, we would expect between 22,000 to 26,000 eviction filings in Harris County during Census 2020.

Source: Data from Harris County Justice of the Peace Court, 2016-2020

Even when evictions are suspended, we can see from past trends that tens of thousands of people could live under the threat of eviction during the Census 2020 enumeration period. This is significant. For context, the entire undercount for Harris County in 2010 was estimated to be about 60,000 people.

Already, we are seeing the effects of Judge Hidalgo’s suspension of evictions, and the subsequent Texas Supreme Court order, in the filing data for March 2020. While eviction cases can still be filed, March will likely end with about half of the monthly average number of eviction cases filed.

Neighborhoods and Communities at Greatest Risk

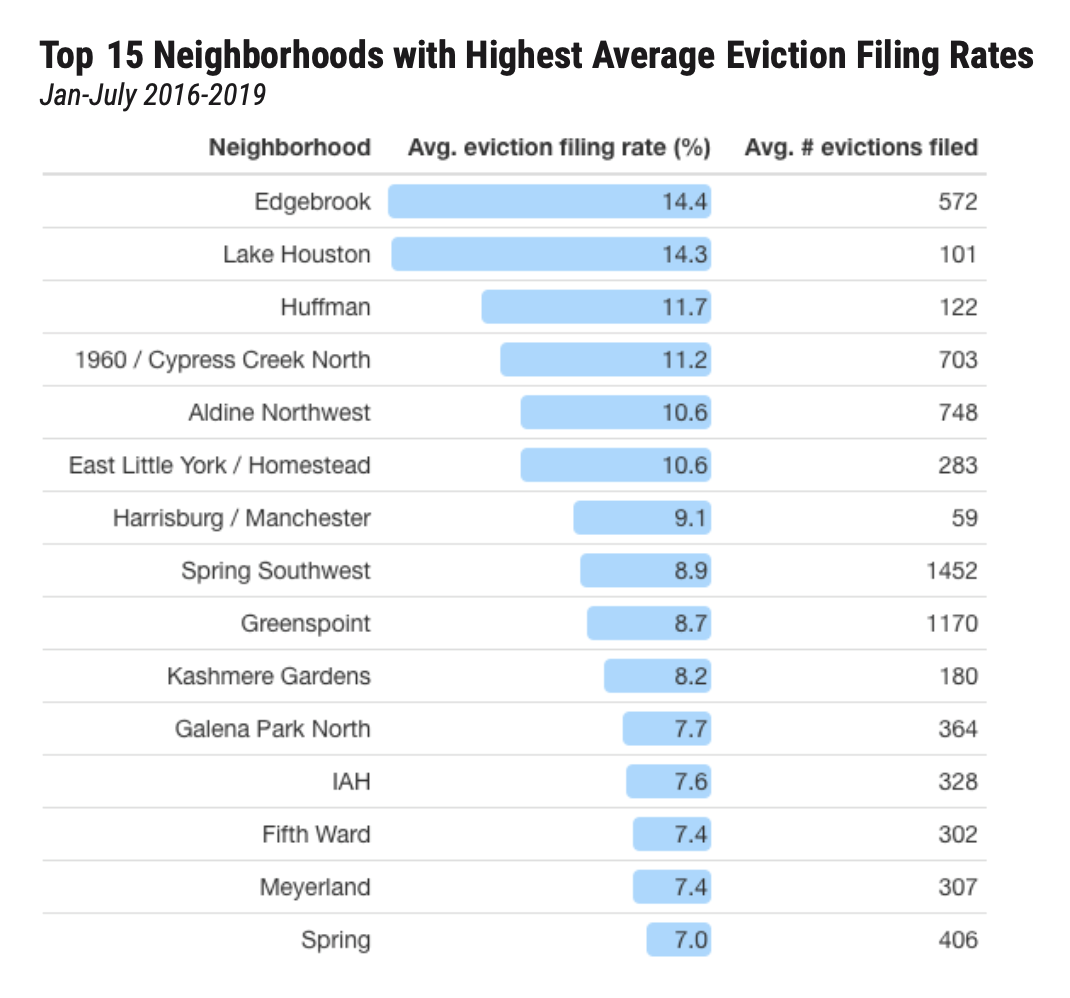

Where are these evictions likely to take place? We geocoded the addresses of all the eviction filings and calculated the average eviction filing rate (number of eviction filings divided by the number of renter-occupied households) between January and July in 2016-2019. Then we aggregated the data for 143 Kinder neighborhoods across Harris County. We adjusted for years and neighborhoods where there were a small amount of renters and a one-time eviction event that skewed the average.

Eviction filing rates across Harris County

Average eviction filing rates by Kinder Neighborhood, January-June 2016-2019

The neighborhoods with the most eviction activity were:

Source: Data from Harris County Justice of the Peace Court, 2016-2019

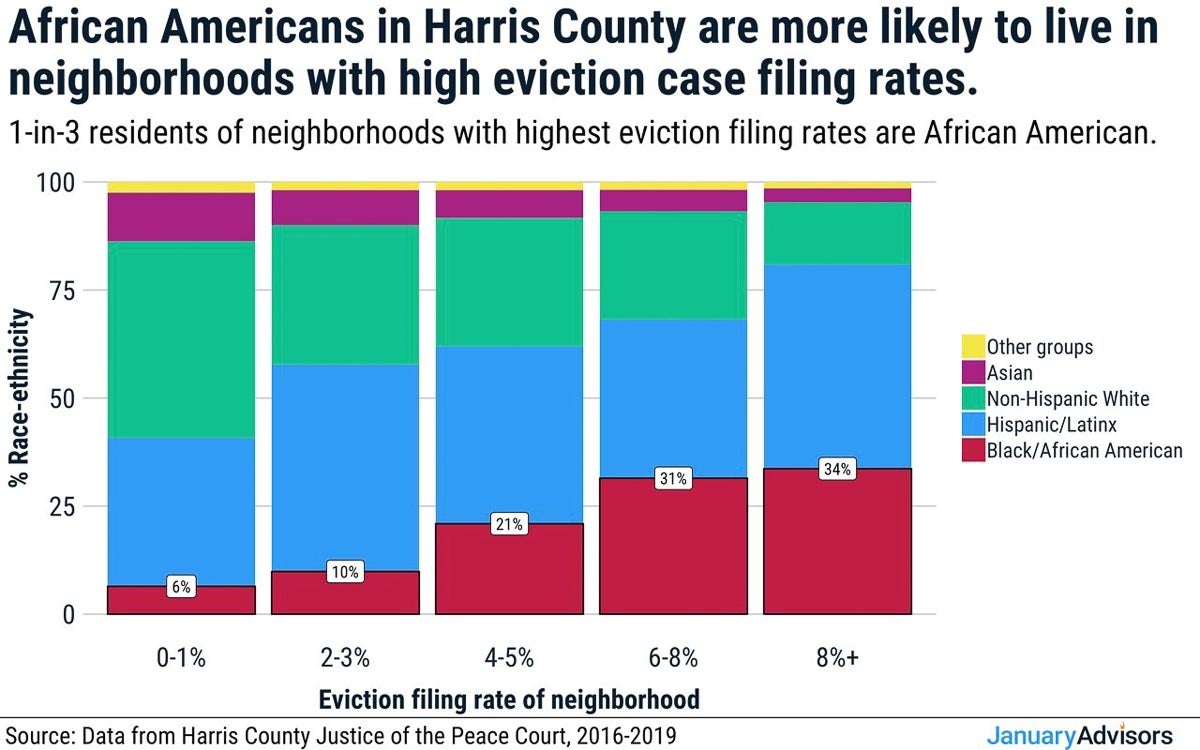

By contrast, non-Hispanic whites and Asian populations make up larger shares of neighborhoods with low eviction filing rates (46% and 11%, respectively) and are much less likely to live in neighborhoods with high eviction filing rates (14% and 3%).

There is no clear relationship between the share of Hispanic residents and the eviction filing rate across neighborhoods – around 35%-45% of residents in neighborhoods with the lowest and highest eviction filing rates are Hispanic. However, it should be noted that our analysis only includes court data, and there are an unknown number of tenants that leave their home after receiving a Notice to Vacate and prior to their landlord filing an eviction case. They would not appear in a court dataset.

This strong effect on the African-American community is consistent with national research from the Eviction Lab. As Mathew Desmond observed in Milwaukee in Evicted, “If incarceration had come to define the lives of men from impoverished black neighborhoods, eviction was shaping the lives of women. Poor black men were locked up. Poor black women were locked out.”

If we don’t continue to pause evictions in the coming months in Harris County, then African Americans will be at greater risk of being undercounted on the census.

Weighing the cost of eviction

If stopping evictions will provide housing stability during the Census, and housing stability during the Census will lead to a more complete count, then how much would it cost? After all, rent is still due.

The eviction data we analyzed includes a judgment amount, which is usually the amount of rent owed. In 2019, the average judgment in an eviction owed to landlords between March and May was $1,300. Of course, when we add up all eviction cases during those months in 2019, the number is much higher: $21 million.

But consider the potential costs associated with an undercount. If Harris County missed just 1% of its residents, as it did in 2010, the State of Texas could lose over $500 million in Medicaid and CHIP funding, not to mention millions more in federal funding for the National School Lunch Program, Community Development Block Grants, and other infrastructure programs.

Taken side by side, the cost of an undercount to our community far exceeds the temporary debt that tenants owe to their landlords. While that debt is still important, the temporary pause on evictions also provides a window of opportunity for housing support services to help stabilize people who are vulnerable. Property owners can be part of the solution, and government programs should consider their needs as well.

While You’re Here, Please Respond to the Census

Fortunately, it has never been easier to fill out the census. This year you can fill out the form three ways: online at 2020Census.gov, by mail, or over the phone. It’s ten questions and will take less than ten minutes.