An estimated 135,000 single family homes and 200,000 apartment units were impacted by Hurricane Harvey. But preliminary findings from the Hurricane Harvey Registry released Thursday underscore the storm's significant mental health impacts, in particular, just how far-reaching the health and housing effects truly were.

"While we want to give our primary attention to people who flooded and lost their homes and are still going through renovations," said Rice University Provost Marie Lynn Miranda, who led the collaborative registry effort with the university's Children's Environmental Health Initiative and has extensive experience in post-disaster research, "there's a large segment of the population who did not flood but who also experienced significant health effects from the storm."

Launched in April 2018, the Hurricane Harvey Registry is the first of its kind to capture the health and housing effects of a severe weather event, modeled after a similar registry was created in the years following 9/11. The collaborative effort between Rice University, the Houston Health Department, Harris County Public Health, Environmental Defense Fund and the National Institute of Health has already received some 13,600 responses with a goal of 50,000 responses as the registry continues to collect responses.

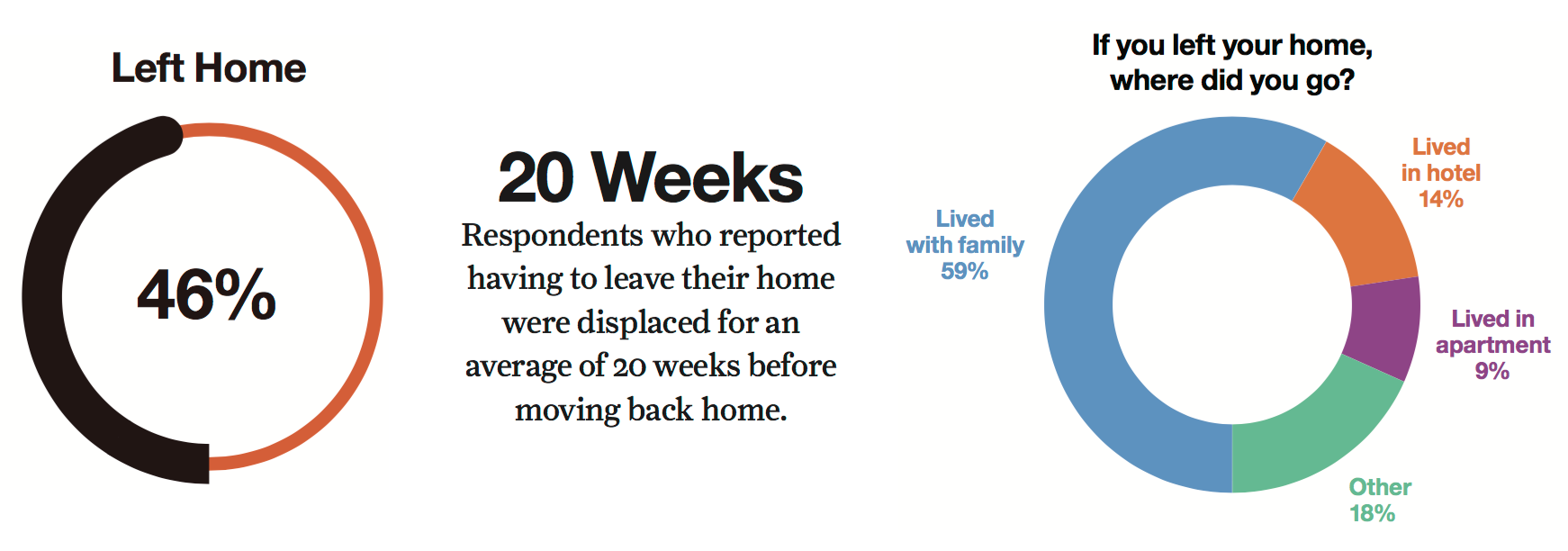

Some 46 percent of the roughly 10,000 survey respondents included in the initial findings reported being displaced from their homes due to the storm for an average of 20 weeks, while 55 percent of respondents reported home damage and 44 percent reported flooding. Most respondents who had to leave their homes reported staying with relatives before returning home.

"Many residents are still displaced, as we know, and the city is working hard to help them return to their home—repairing homes, reconstructing homes—and that process will be going on for the next three to five years," said Mayor Sylvester Turner, helping present the initial results Thursday.

Source: Harvey Registry.

Among the notable preliminary findings is the extent of the storm's mental health impacts. Fifty-nine percent of respondents said they thought about the storm when they didn’t mean to and 52 percent said images of the storm popped into their minds.

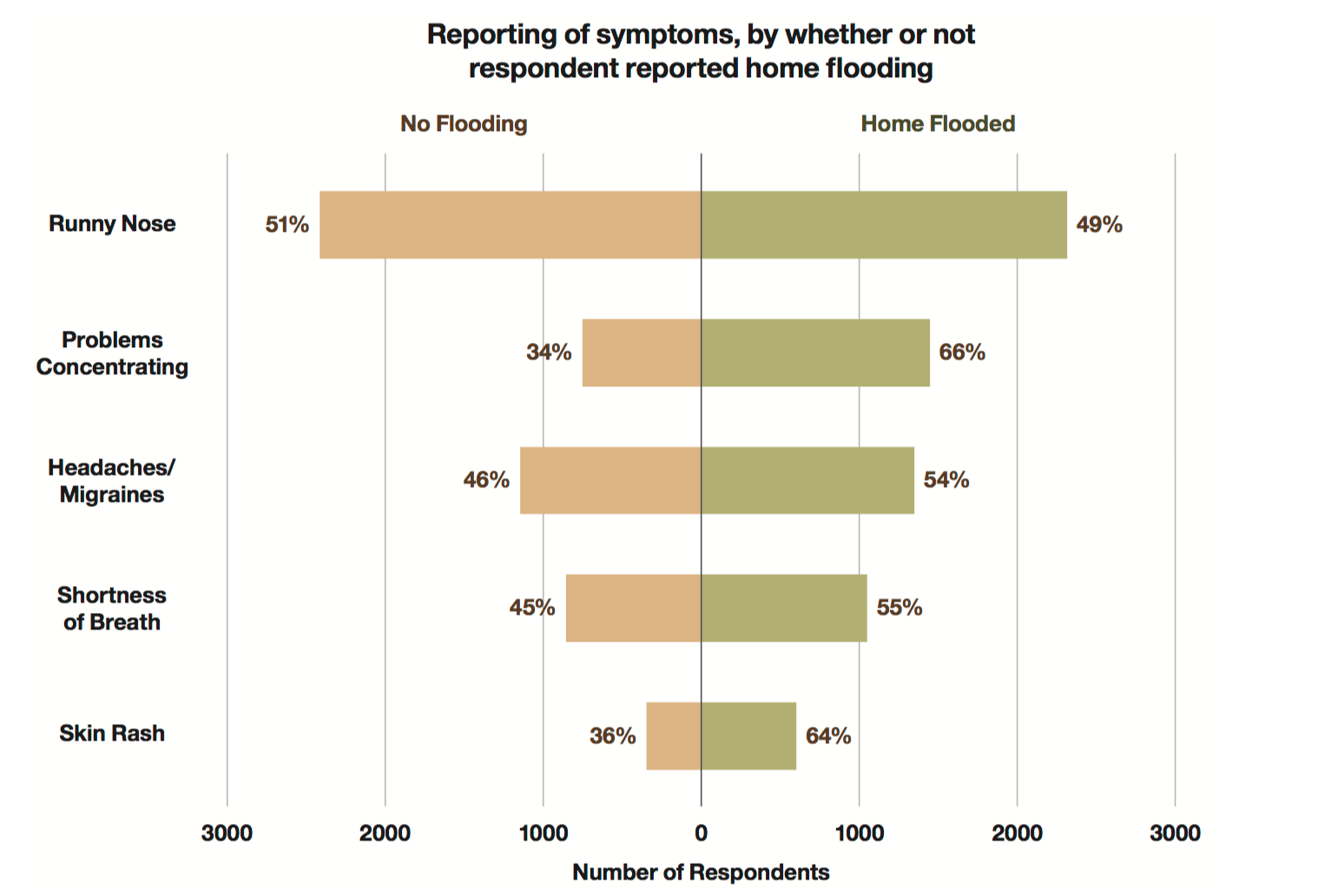

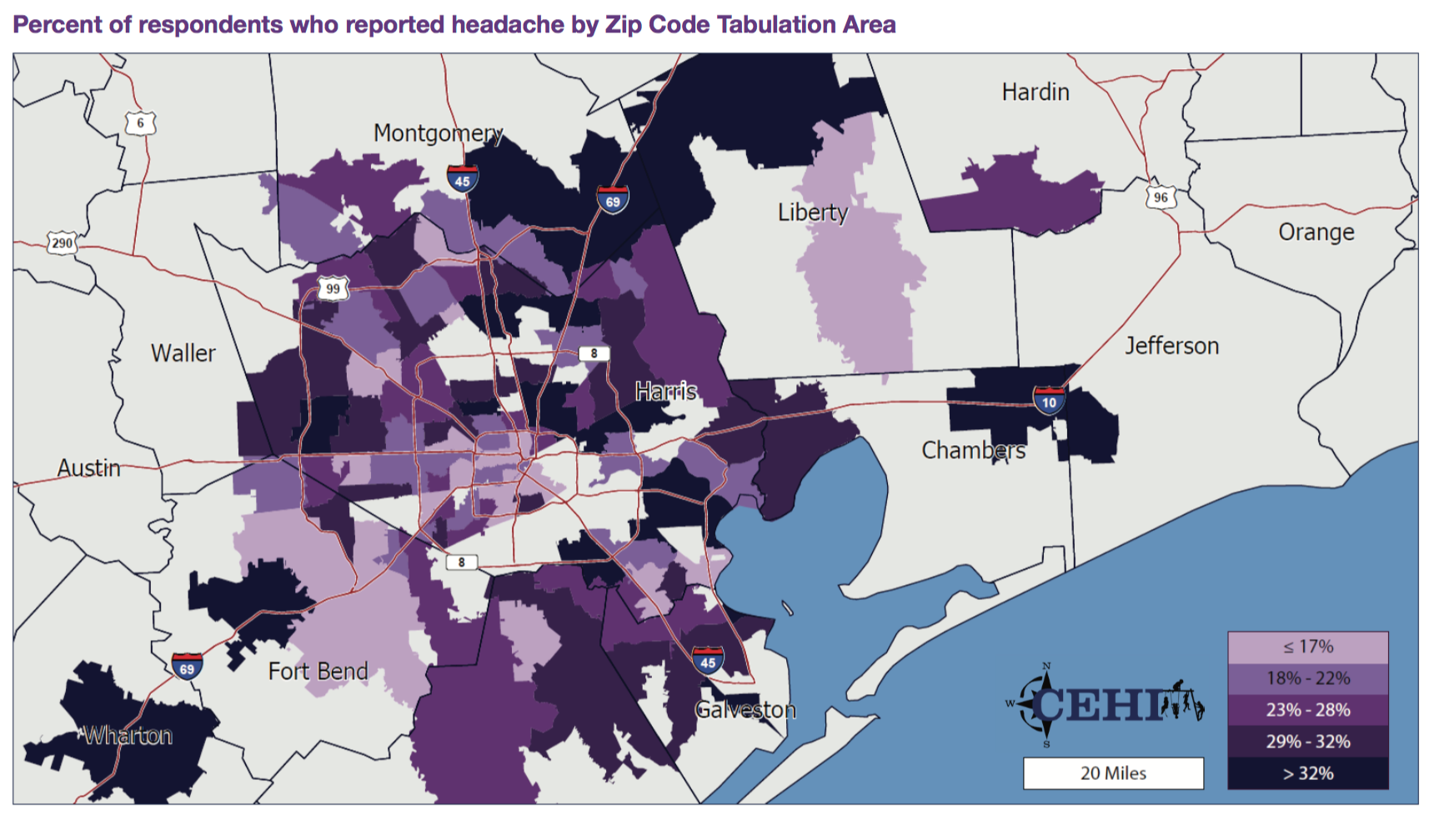

The survey results also documented the health impacts experienced even by those whose homes did not flood. Almost half of the respondents who didn't experience flooding still reported having significant headaches after the storm, for example.

Source: Harvey Registry.

"These findings reinforce my longstanding concern that even though our city has bounced back from Harvey," said Turner, "we still have more healing to do. And I pledge to make the resources of the city health department and other branches of city government available to act on the findings of the survey.”

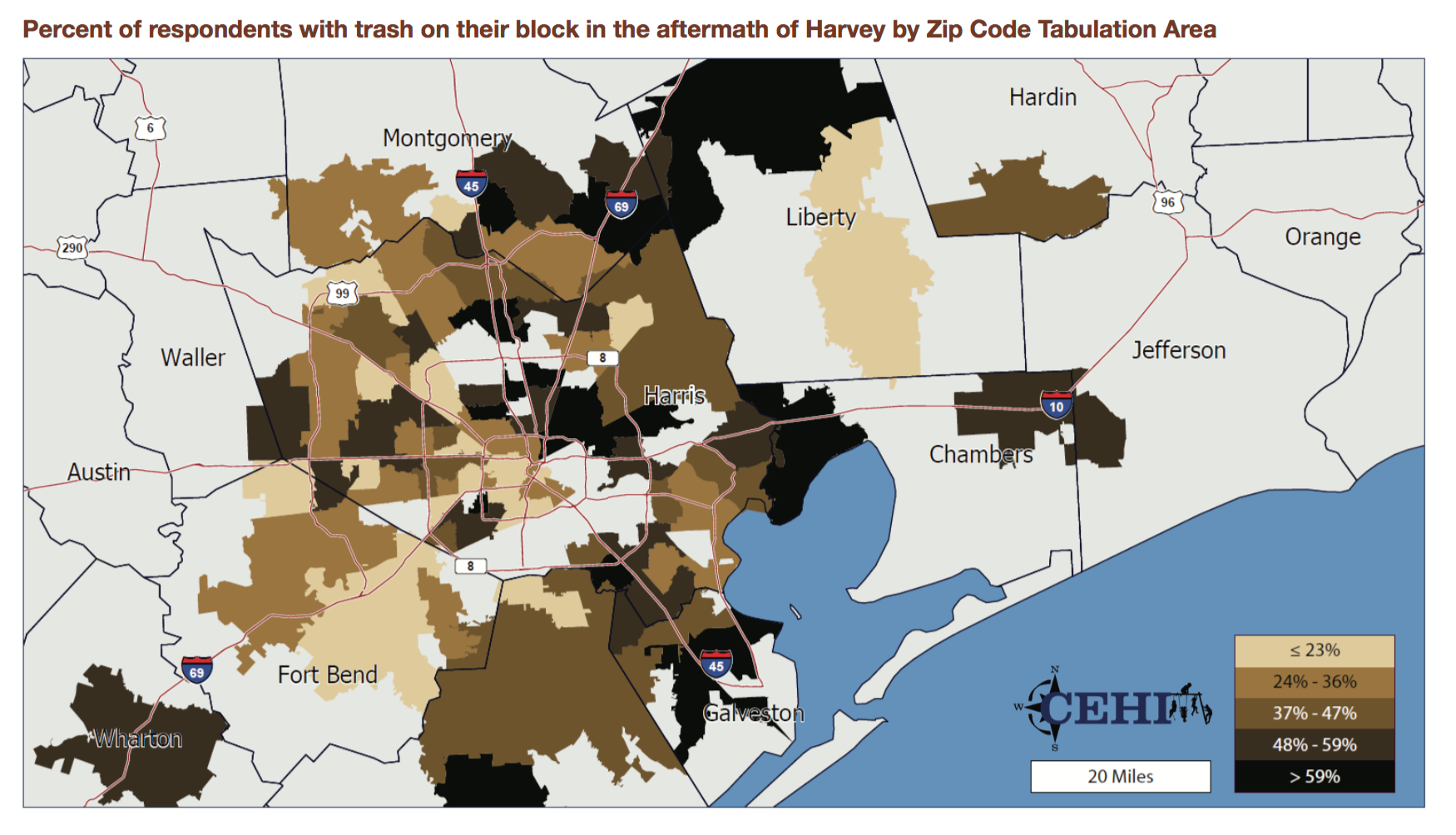

In addition to the self-reported data, the registry also layers things like school locations, industrial sites, socioeconomic information and other data to contextualize and analyze the findings. "We have data layers of what areas flooded and which ones didn’t, where were there trash piles, where were there industrial plants, which, if they got flooded, there may have been things in the flood water," said Miranda. "It's all connected."

Source: Harvey Registry.

Source: Harvey Registry.

Researchers and community activists have called attention to the health impacts, both known and unknown, since the storm hit. "We know Hurricane Harvey exposed Houstonians to increased air pollution, water pollution and soil contamination as well as mold inside their homes among other threats," explained Loren Raun, chief environmental science officer for the Houston Health Department and a Kinder Fellow.

Both the city and county health agencies said they are using the survey, currently offered in both English and Spanish, to help guide planning and response efforts, like Harris County's periodic Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response surveys and pop-up mobile health clinics.

"Houston is leading the way in understanding the long-term effects of extreme weather events,” said Elena Craft, senior health specialist with the Environmental Defense Fund.

Though the registry has received responses from across the Houston area, Miranda said they are working to reach even more people, including low-income communities and non-white respondents in particular with on-the-ground outreach and paper surveys. The team is also developing the survey in Vietnamese and Mandarin.

"More people need to take the survey so that we can learn from them," urged Turner.