In Houston's Northern Third Ward neighborhood, community groups have been pushing back against gentrification that has claimed other historically black neighborhoods near downtown. Residents there point to Freedmen's Town, remnants of which are tucked inside a fortress of townhomes and apartment buildings, as a cautionary tale. As property values have risen, along with rows of multi-story townhomes, in Third Ward, community members there have been organizing to resist the displacement and erasure that characterize gentrification.

In a recent study, however, Rice University's Lester King and Texas Southern University's Jeffrey Lowe draw attention not just to the strategies that have emerged from years of organizing but to the very fact of the organizing itself as an innovative moment for a traditionally market-oriented city with historically weak neighborhood planning infrastructure. While Third Ward's trajectory is familiar to many core neighborhoods that saw thriving black businesses and communities diminished by highway construction in the urban renewal era, desegregation and sustained underinvestment, the authors argue that its context is somewhat unique and presents unique challenges to low-income communities resisting displacement.

"Historically, Houston municipal government has favored policies that result in private-sector growth and gentrification rather than community development," the authors write. While many cities embrace boosterism and growth machine politics, the authors point out that Houston "lacks progressive policies such as inclusionary housing requirements" that other major cities have adopted.

Though the city has utilized management districts and special tax increment reinvestment zones to theoretically support community development, those entities have had faced questions, including millions in "lost money" meant for low-income housing. Like the structure of many of those entities means that community is often not prioritized. "Given that board members are not publicly elected," the researchers note, "and that they have little history of fostering community participatory or organizing processes, community development remains ostensibly a non-issue."

Houston also has a relatively anemic neighborhood planning history, as the case study points out. Though neighborhood planning was undertaken by the city in the 1990s, "[o]ver time, the formulation of neighborhood plans became a tall order." The city's planning department was restructured and Super Neighborhoods were later formed as an avenue for community organization. But those organizations lacked the benefit of dedicated neighborhood planners and became "linked more directly with the Office of Neighborhoods, which is mostly responsible for 'non-planning' activities such as code enforcement, service delivery, and community relations," according to the authors.

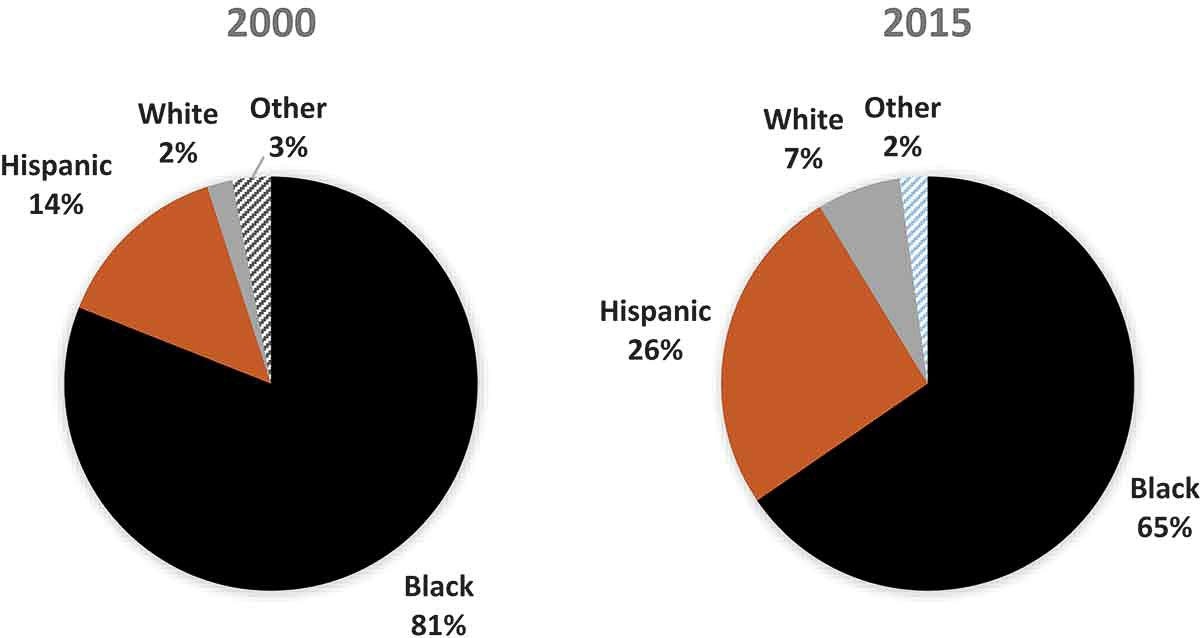

Northern Third Ward Race/Ethnicity 2000 and 2015. Data: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey. Source: "We want to do it differently": Resisting gentrification in Houston's Northern Third Ward.

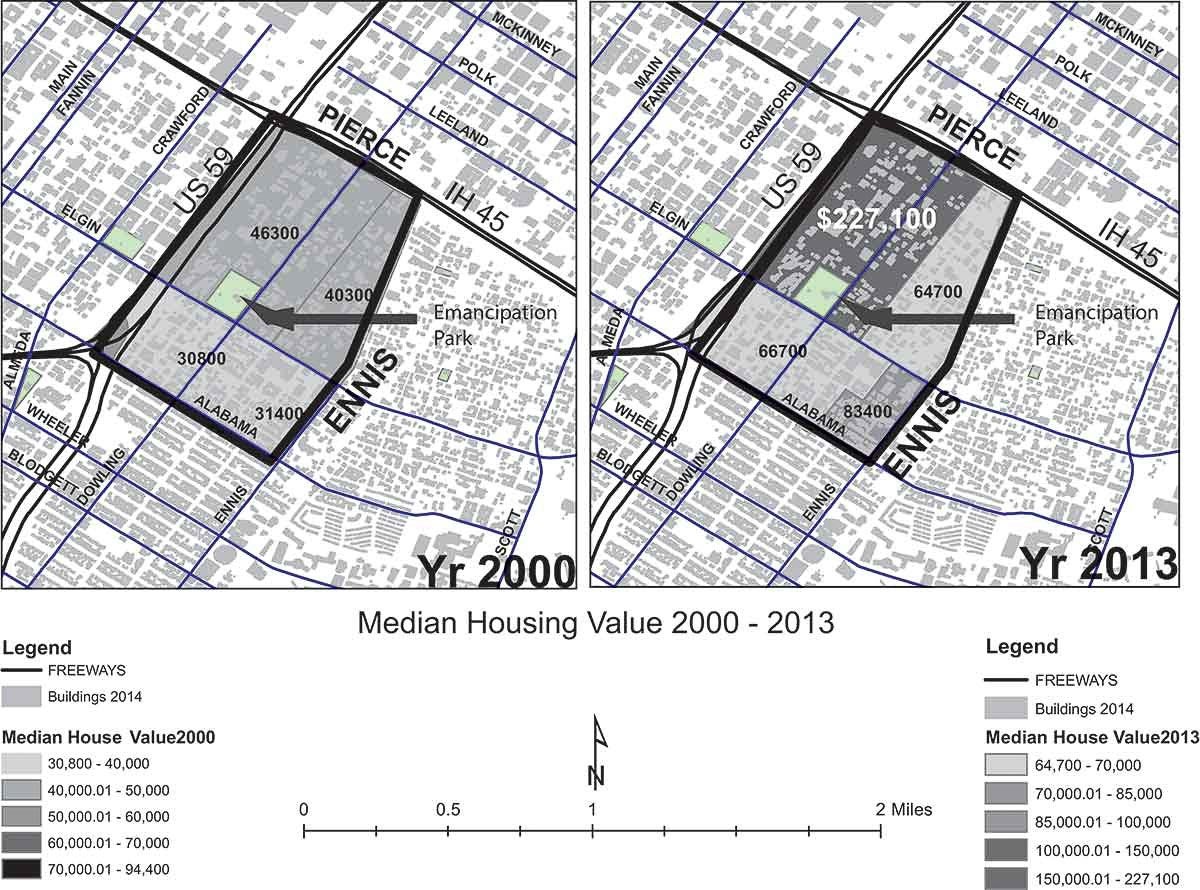

Northern Third Ward median housing value, 2000 and 2013. Data: American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2013, Decennial Census. Source: "We want to do it differently": Resisting gentrification in Houston's Third Ward.

More recently, the city's pilot Complete Communities initiative, selected five neighborhoods, including Third Ward, to engage in a participatory planning process but the future of the resulting plans and the initiative is still uncertain.

The overall lack of neighborhood planning and infrastructure meant that there were few effective avenues, if any, for poor communities of color to guide neighborhood change.

"The bias in public investment favoring privatized speculative land development over neighborhood revitalization of the built environment and community development explains why some of Houston’s poor communities of color lack influence over land-use decisions," the authors argue.

The case study focuses on the Emancipation Economic Development Council over a two-year period starting in 2014. Focusing on the community organization's housing and community land trust group, the researchers examine how the community has organized to respond to neighborhood change and the threat of displacement, particularly in Northern Third Ward, focusing on the area around the recently renovated Emancipation Park. The community land trust emerged as a possible strategy to help residents remain in their neighborhood, particularly low-income residents, who might otherwise be priced out as property values and taxes rise.

Several organizations were considered to help launch the community land trust, including one of the redevelopment authorities and TIRZs that owns a substanial amount of property in the neighborhood, a community development corporation and local churches and faith-based organizations that also own land in Northern Third Ward. But each option came with challenges, including concerns about "uncharted territory" and resistance to the idea of community-owned property. "Growing up in Houston," one work group member stated, "we were taught no other way to build wealth except through home ownership and property. Most black folks don’t own anything but their homes, and since slavery some people didn’t want us to have that. I want to have something of value to leave my children and I am not going to give [property ownership] up."

While the idea of a community land trust is still evolving, the researchers argue that EEDC has already succeeded in opening up participatory spaces and producing new ideas that challenge the long-held notion of wealth creation through property. "What remains to be seen for Northern Third Ward community development over the long term, and as a matter of social justice," the authores write, "is whether mobilization will sustain a collective agency that produces favorable outcomes toward power and community control or give way to norms more supportive of profit maximization through private property as propagated by way of gentrification."