A recent study provides evidence that black renters pay more for rent than white renters for comparable housing in the same neighborhood. The gap between those two groups also grew as the percentage of white people in the neighborhood increased, according to the paper.

The study represents one of the most robust and recent analyses of rent premiums paid by black households, pulling from surveys given to voucher holders collected by the federal housing department in 2000, 2001 and 2002. In each of those years, the survey was mailed to more than 250,000 families across the country participating in the voucher program, through which income-eligible renters receive subsidies to help make rent affordable. Generally, renters in the program spend 30 percent of their income on rent, with the federal subsidy going directly to landlords to make up the gap between the renter's share and the actual rent. If the renter finds a unit charging more than the payment standard set by the local public housing agency, the renter is also responsible for the amount of rent above that standard. During the study period, the total amount that a renter contributed to rent could not exceed roughly 40 percent of their income.

Though the data set is limited to voucher holders, the results are still relevant to the unsubsidized rental market. "Research suggests rents paid in the voucher program appear to be market rents," explained Dirk W. Early with Southwestern University's department of economics and business, co-author of the paper with Paul E. Carrillo with George Washington University's department of economics and Edgar O. Olsen with University of Virginia's department of economics. "Of concern to some is whether landlords [who] are likely to discriminate are less likely to accept vouchers. If that is true, our estimates will underestimate the rent premiums in the unsubsidized sector."

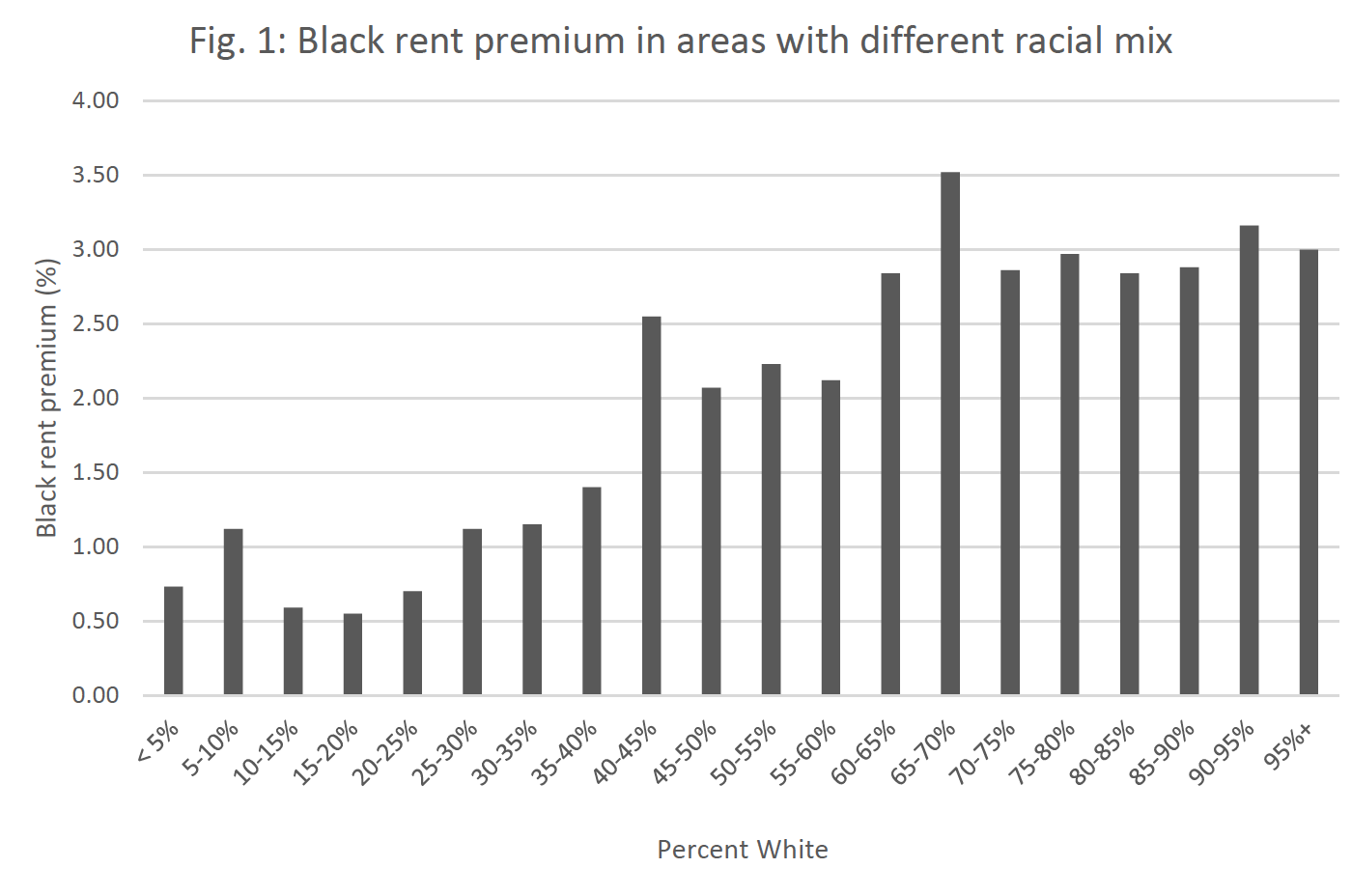

Black rent premiums as the percent of the white population in the area increases. Source: "Racial Rent Differences in U.S. Housing Markets."

Even with a voucher, housing is not a guarantee. Discrimination against renters with vouchers has been well reported and documented. Some renters have had to give their voucher back when they were unable to find a landlord who would rent to them. While some jurisdictions protect voucher holders against a so-called source of income discrimination, many do not, including Texas, which actually prohibits the enactment of ordinances that would protect renters with vouchers.

"The voucher program is one of the biggest programs," explained Tory Gunsolley, president of the Houston Housing Authority, at an affordable housing symposium sponsored by the Kinder Institute in 2017. "And you can't live in a voucher," Gunsolley recalled families having to give back their vouchers because they were unable to find an affordable place that would accept it. "Section 8 landlord discrimination is legal in Texas," he said, "and that's a huge problem."

A 2017 lawsuit alleging that the state ban on anti-source of income discrimination policies is unconstitutional is still pending.

Landlords claim that working with voucher holders can mean cumbersome red tape, that there "can be delays in payments, and security deposits are not always covered," according to Governing magazine. But research also suggests the reasons for not wanting to rent to voucher holders are sometimes explicity racist as well.

The more than 400,000 survey responses, combined with Census data, offer a unique level of detail about the households, housing units and surrounding census block groups, including things like school quality, the presence of vacant buildings and crime. Given the robust, national dataset and the relatively recent years of data collection, the authors argued that the paper "yields the first highly credible evidence on patterns of racial rent differences in recent times."

The findings connect to research about discrimination in the non-subsidized market as well. In Houston, for example, a recent study documented the compounding layers of discrimination that shaped outcomes for black homebuyers.

Though the analysis of voucher holders found differences between non-Hispanic whites and other groups generally in terms of rent, the largest difference was between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks. "The premium is negligible in heavily black areas and about 2.4 percent in areas with the highest fraction white," according to the paper. The relationship was largely the same for metropolitan areas as well as non-metropolitan and rural areas and across metropolitan areas with varying levels of white-black segregation.

A detailed breakdown by metropolitan area of the rent premium within neighborhoods that are at least 80 percent white is included above but Early cautioned that, because the data set necessarily gets smaller as you scale down, ranging from 322 to 7,463 observations, the results may not be as robust as those on the national level.

Though the study speaks to the experiences of black voucher holders, it has implications for racial discrimination across the rental market and mirrors other research about differences in sale price for comparable units in the same area between black and white buyers.