Following a study that documented the ways in which Harris County's appraisal district perpetuated racial inequalities, Elizabeth Korver-Glenn, an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, is out with another study that looks at how the home buying process involves stereotypes and discrimination that accumulate over each stage and ultimately drive unequal outcomes based on race. The findings help explain why racial inequality has remained so persistent despite legal shifts meant to protect against racial discrimination, particularly in real estate and housing.

After one year of fieldwork and more than 100 interviews, Korver-Glenn found that both individual and institutional practices had a hand in shaping the disparate outcomes from finding a real estate agent to applying for a loan and assessing home value. And the impacts, given the established research on the effects of neighborhood-level inequalities, are far-reaching.

"Ultimately, I think that the compounding inequalities I observed perpetuate segregation and associated inequalities in education, wealth, and health (among others) in Houston," Korver-Glenn wrote in an email, "and will continue to do so unless there is a significant collective will to intervene in discriminatory practices and the private market institutions that enable them."

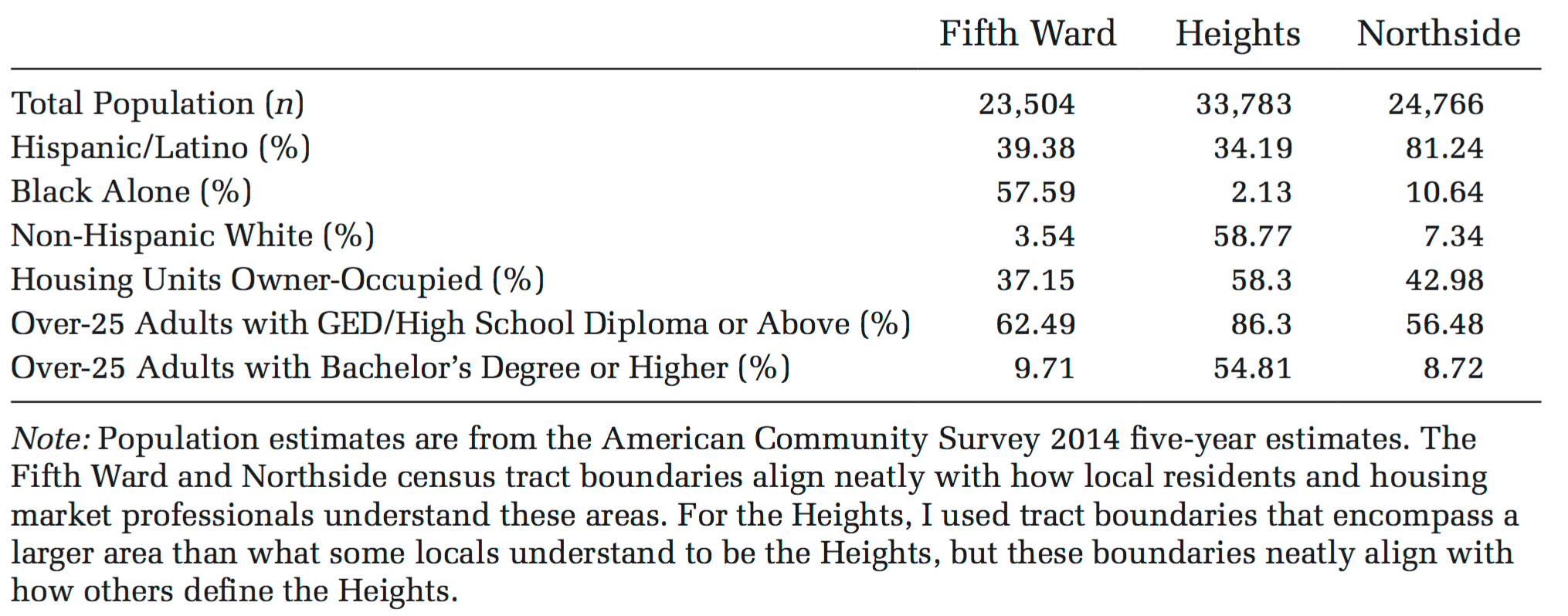

Though Houston touts its diversity, the study notes that the metropolitan area's black-white segregation is on par with that of the Washington, D.C. or San Francisco metropolitan areas. And its white-Hispanic segregation is comparable to that of the Miami and Chicago metropolitan areas. Underscoring that point, Korver-Glenn began her research in three nearby neighborhoods with very different compositions: Fifth Ward, Heights and Northside. All among the "oldest neighborhoods" in the city, the study notes, and each having experienced some period of decline in the second half of the 20th century. "Over the past 20 years, these neighborhoods have diverged in terms of socioeconomic status," the study notes.

As she followed real estate agents, developers and other stakeholders across the Houston area, she found that many of the practices she observed in these three neighborhoods extended beyond them as well.

Neighborhood demographic characteristics. Source: Elizabeth Korver-Glenn.

Korver-Glenn spent countless hours in the field: 118 go-alongs with 13 different real estate agents and developers; 102 interviews with agents, developers, lenders, appraisers, escrow officers, home sellers and buyers, landlords and renters and other stakeholders; 222 in-the-field encounters.

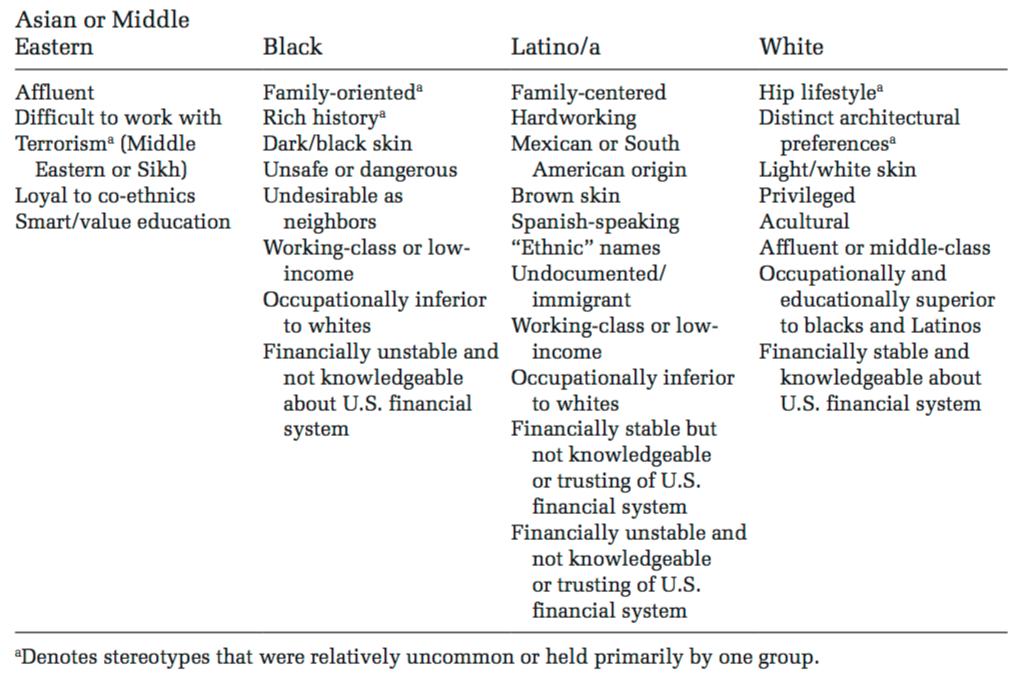

At each stage of the process, the study found that stakeholders either "used or reported others using widely shared racial stereotypes." These stereotypes often came with a sort of hierarchy.

Shared racial stereotypes. Source: Elizabeth Korver-Glenn.

In looking at four major stages of the homebuying process, the study documents how individual stakeholders, as well as institutionalized practices, amplify these stereotypes.

Establishing and Maintaining Real Estate Agent-Client Relationships

Because real estate agents often rely on personal networks and building trust with their clients, the study found that they often relied on "tacitly legal behaviors that code or signal racial stereotypes but assuage their ethical or legal concerns." Agents often either acted on racial preferences stated in coded or direct language or operated based on what they "believed those preferences would be."

One white agent, the study notes, had a home seller who didn't want to sell to a Middle Eastern client "because he did not want to 'support terrorists.'" Other white agents said white sellers often didn't want to sell to black buyers because they assumed it would affect home values for their white neighbors. These agents only "rarely" reminded clients that they could not discuss race and never refused to work with someone who expressed explicitly discriminatory preferences, the study notes.

While the study notes that some Asian, black and Latino agents also talked about anticipating perceived racial preferences, "this occurred infrequently compared to white agents' discussions and, when it did occur, it was usually in the context of accessing family and cultural goods like food." So while 81 percent of 21 white real estate agents interviewed and observed used racial codes to give clients advice and talk about neighborhoods, only 45 percent of non-white agents did.

Marketing a House for Sale

When it came to marketing a house, the study again found the use of racially discriminatory practices underpinning a "spatialized hierarchy of race." First, through a housing listing database that prioritizes "specialization for majority-white areas" through its system of neighborhood boundaries and second, through the real estate agents' assessments of clients' potential risks.

Pretty much everyone who wants to buy a home ends up on HAR.com, the listing site of the local real estate board, where users can search by neighborhoods. Listing a property here is a typical first step for real estate agents selling a home and the site automatically sorts properties into uniquely drawn market areas. Korver-Glenn documented 98 market areas that included some portion within the City of Houston during the study period and found that 70 of them were largely one race. Within that, 50 were majority-white, a overrepresentation in a city where less than a third of the population is white. Furthermore, these areas tended to be smaller, with an average of about 20,000 people in a majority-white market area compared to an average of 61,000 and 88,000 people in majority-black and majority-Latino areas. This specialization and prioritization of white spaces worked to further cement segregation.

Individual-level actions also contributed to unequal outcomes when it came to marketing. The study found that real estate agents, particularly white agents, made race-based assumptions about buyers, including whether they "posed financial and safety concerns," or if they would be a waste of time to work with. One white escrow officer who had worked as a real estate agent remembered working at a firm where people working an open house would "call someone for backup" if a black person came to view the home because "they would think they were there to steal."

Evaluating Mortgage Loan Applications

Similar risk assessments based on race were present in the evaluation of mortgage loan applications, according to the study. The required application for people seeking a loan on a single-family home includes information about the buyer's ethnicity, race and sex for monitoring purposes. But if the buyer chooses not to fill that out, the loan officer or originator is supposed to do so if the form is completed in person, using "visual appearance and surname" to guide them. Six of the 10 loan officers interviewed reported doing so, even if the forms weren't completed in person. All that information was then shared with the underwriters to review. One loan officer recounted a story from a colleague at another mortgage company of a black couple that got "scrutinized to death" and ultimately declined despite being well-qualified for the loan. Other investigations have also documented how mortgage discrimination is a persistent problem for people of color.

Assessing Home Value

Assuming the loan application is approved, the house has to be assessed for the loan to go through. This is done using "comparable homes" through a process the study found was "largely individualized." This presented yet another opportunity for stereotypes to enter the process with significant material outcomes. The study also found that agents and lenders often tried to sway the outcome.

"By this time in the housing exchange process," the study concludes, "the minority buyer--if not at some point categorically excluded--has been repeatedly subjected to widely shared racial beliefs about their ability to care for homes, financial instability, potential for danger, and desirability as a neighbor."

One of the major takeaways here is that existing policy is not being enforced. "I think what's on the books (weak as it is) has to be enforced," Korver-Glenn wrote in an email. "Fair housing legislation has never been adequately enforced, and I think this contributes to the sense among real estate professionals that (coded) stereotypes and subtle forms of discrimination are insignificant." Likewise, at the institutional level, many practices that have specific racial outcomes are presented as race-neutral, providing "a kind of color-blind cover for individuals working within them."

But, she argued, there are ways to go beyond federal policy. "There are several other ways to help interrupt contemporary discrimination, and I think they would each be most impactful if they were applied simultaneously," she continued. "These include: incentivizing real estate agents to work in communities of color (perhaps through providing brokerages tax breaks when their agents do so); promoting a flat-fee, rather than percentage-based, approach to real estate brokerage; relying on automated mortgage underwriter software that examines income/credit characteristics and/or obscuring mortgage borrower name, race/ethnicity, and sex information so that underwriters cannot view it when evaluating applicant risk; and standardizing the appraisal process by requiring appraisers to use an automated software that draws comparable home sales from across the metropolitan area."

In the meantime, she said, homebuyers and agents of color are well aware of the systemic discrimination that shapes the market and have found ways to respond. "Realtors of color," she wrote, "responded to and attempted to disrupt exclusion in different ways," including reporting others for fair housing violations. "Other strategies I heard or observed included recommending clients to trusted lenders and encouraging them to avoid lenders with reputations of treating borrowers of color unfairly; giving buyers of color a 'break' on commission (e.g. taking 4 percent instead of the usual 6 percent); and intentionally cultivating relationships with other professionals of color, such as lenders," she added.