Early in his career, Mexican artist Diego Rivera painted seemingly familiar still-lifes of fruits and other foods. Later, his vision would turn outward, integrating workers in factories and fields into his now famous large-scale murals. For Houston legend Felix Tijerina, the odyssey was reversed. He left the fields and became a restaurateur creating what became familiar plates of food.

On the surface, Rivera’s journey seems to take the opposite tack of Tijerina’s journey but their journeys are more alike than they appear. Their views evolved from small intimate spaces of survival to broader visions of systems and politics.

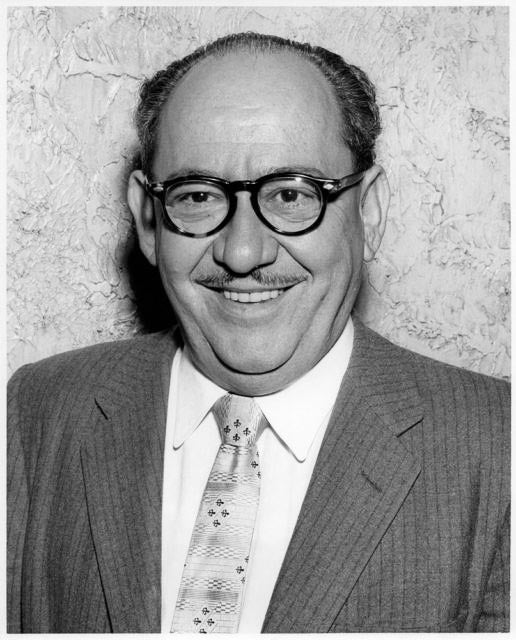

Photograph, Portrait of Felix Tijerina.

Courtesy of Houston Digital Library.

The recent Museum of Fine Arts, Houston exhibit “Paint The Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950” featured two of Rivera’s early still-lifes. One, clearly influenced by Pablo Picasso’s cubism, Naturaleza muerta con limones(1916), is an array of joyful blue and red planes punctuated by three bright yellow lemons. The other, showing the influence of Paul Cézanne, Naturaleza muerta con botella de anis (1918), is more somber and realistic, composed of muted apples and oranges, a bottle of anise liqueur, and a decanter. Both are intimate portrayals of food.

Later in the exhibit, there were large digital projections of the murals Rivera is better known for. Born from the politics of the Mexican Revolution, Rivera’s large-scale works are as much influenced by Aztec art as European. They look outward, showing the people, the politics, and the workers that grew and harvested the food.

The same revolutionary furor that inspired Rivera also lead to violence and turmoil that forced some of those Mexican workers and farmers to immigrate to Houston in the 1910s and ’20s. One of them was Felix (née Feliberto) Tijerina, who became one of Houston’s best-known restaurateurs and civic leaders.

Tijerina was born in 1905 to farmers in General Escobedo, Mexico, which is now part of the Monterrey metropolitan area and borders Cerro del Topo Chico — the source of Topo Chico mineral water. In 1915, after two Mexican Revolution battles were fought in the area and the death of his father, Tijerina and his family immigrated through Brownsville, Texas. Like many Mexican immigrants then, and now, his family worked as migrant farm workers in south Texas.

They eventually found their way to Sugar Land. There, young Tijerina worked menial jobs for Imperial Sugar and Sugarland Industries. To help supplement his income, he occasionally sold chickens at Houston’s Market Square, where Mexican immigrants had been selling tamales, chili, and other foods since the late 1800s.

Leadbelly, the blues and folk singer.

Photo from the Library of Congress, Alan Lomax Collection.

Tijerina was living in the Sugar Land-area in 1918 when famous blues musician Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter began serving his sentence at the Imperial State Prison Farm in Sugar Land. Lead Belly’s time there inspired his version of “Midnight Special,” which, among other things, documented racial discrimination and brutality in the Houston Police Department of the 1910s and 1920s. The song and Lead’s prison stint also represented a long history of abusive and discriminatory labor practices that began with enslaved Africans working in the sugarcane fields along the Brazos River in Fort Bend County. After Emancipation, the large sugar producers leased the Texas prison population to work the cane fields, subleasing the prisoners they didn’t need to other industries. They also employed sharecroppers and immigrant laborers, many of them, relying on company towns like the one founded by Sugarland Industries and where the Tijerinas lived briefly.

This history is still playing out as Loam Agronomics tries to redeem some of Fort Bend’s prison farmland, which Lead Belly may have worked, at its 288-acre sustainable vegetable farm that is now part of a larger experiment to integrate agriculture with suburban development.

In 1922, after years of low wages and racial discrimination, 17-year-old Tijerina and his family moved to Houston in search of better prospects. He soon found a job loading and unloading produce for Jewish entrepreneur and son of Austrian immigrants Sig Frucht, who operated a wholesale company that sold fruits and vegetables Frucht bought from south Texas farmers, who often employed migrant workers from Mexico.

Within a few months, the ambitious Tijerina found a job as a busboy at the Original Mexican Restaurant at 1109 Main Street. Owned by Anglos George and Bessie Caldwell, the restaurant was an early attempt to appropriate and adapt Mexican food for a White clientele. Tijerina worked for the Caldwells for the next 6 years, learning not only the restaurant business — he was basically the general manger when he left — but how to navigate both the White and Mexican communities in Houston. This experience led him to eventually open, with his wife Janie González Tijerina, the successful Felix Mexican Restaurant chain and to become an influential civic leader. Ultimately, he became national president of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), one of the oldest Latinx civil rights organizations in the United States. A position he used to improve education for Mexican Americans, especially at the preschool level.

Photo from Loam Agronomics, Fort Bend.

Both Diego Rivera’s and Felix Tijerina’s views evolved from small, intimate spaces of survival to broader visions of systems and politics.

Both progressions follow what is often the general trajectory of our interest in food, from intimate knowledge of the plate to wonder with the larger forces that put that food on the plate, from eating the meals our parents put on the table to struggling to buy and cook our own food. Through the lens of food we can tell both our personal stories and stories about our culture and community. Studying food and foodways touches almost all aspects of society: science, race, urban planning, economics, industrial design, medicine, art, history, architecture, and more.

As Tijerina’s story shows, studying food in Houston reveals a complex history of immigration — Houston wouldn’t have eaten without immigrants — enslaved labor, politics, urban development, discrimination, and relationships that connect us to the wider world around us. It’s a history that digs deeper than oil and gas executives, colorful characters like Glenn McCarthy, and sports teams that usually disappoint. It’s a history that tells us who we are through the food we eat. It’s a story that is still being written in the houses, apartments, and strip centers that line streets such as Long Point, Bellaire, Bissonnet, Richmond, and Westheimer.

David Leftwich is Executive Editor of Sugar and Rice and will be moderating a panel at the upcoming Houston Eats! Conference on February 2nd and 3rd at the University of Houston’s main campus.

This story originally appeared on OffCite, a blog for Cite magazine, a publication of the Rice Design Alliance.