Since the late 1990s, school districts in Texas have increasingly turned to police officers, often through their own district police departments, to address disruptions in school, sometimes with severe results, especially for categories of students who can be brought up on criminal charges and are more likely to have forced used against them. Between 2011 and 2015 in the Houston area, for example, use of force incidents involving school police officers, or school resource officers, include "some instances where officers drew firearms, fired pepper spray, hit students with nightsticks or brought in police dogs," according to the Houston Chronicle.

But a new report from Texas Appleseed and Texans Care for Children suggests there's been a decrease in the overall number of use of force incidents as well as a decrease in arrests, tickets, and complaints issued in recent years, following reforms by the state legislature in 2013.

"We don't get a lot of wins with the school-to-prison pipeline but this feels like a win," said Yamanda Wright, Director of Research with Texas Appleseed, a research and advocacy nonprofit.

Still, the report, which looked at school discipline across the state, found a number of red flags in data provided through information requests to individual districts, including persistent racial disparities and an increase in the share of elementary students involved in use of force incidents. And it highlighted the ongoing reliance on school police officers to address classroom disruptions and behavior.

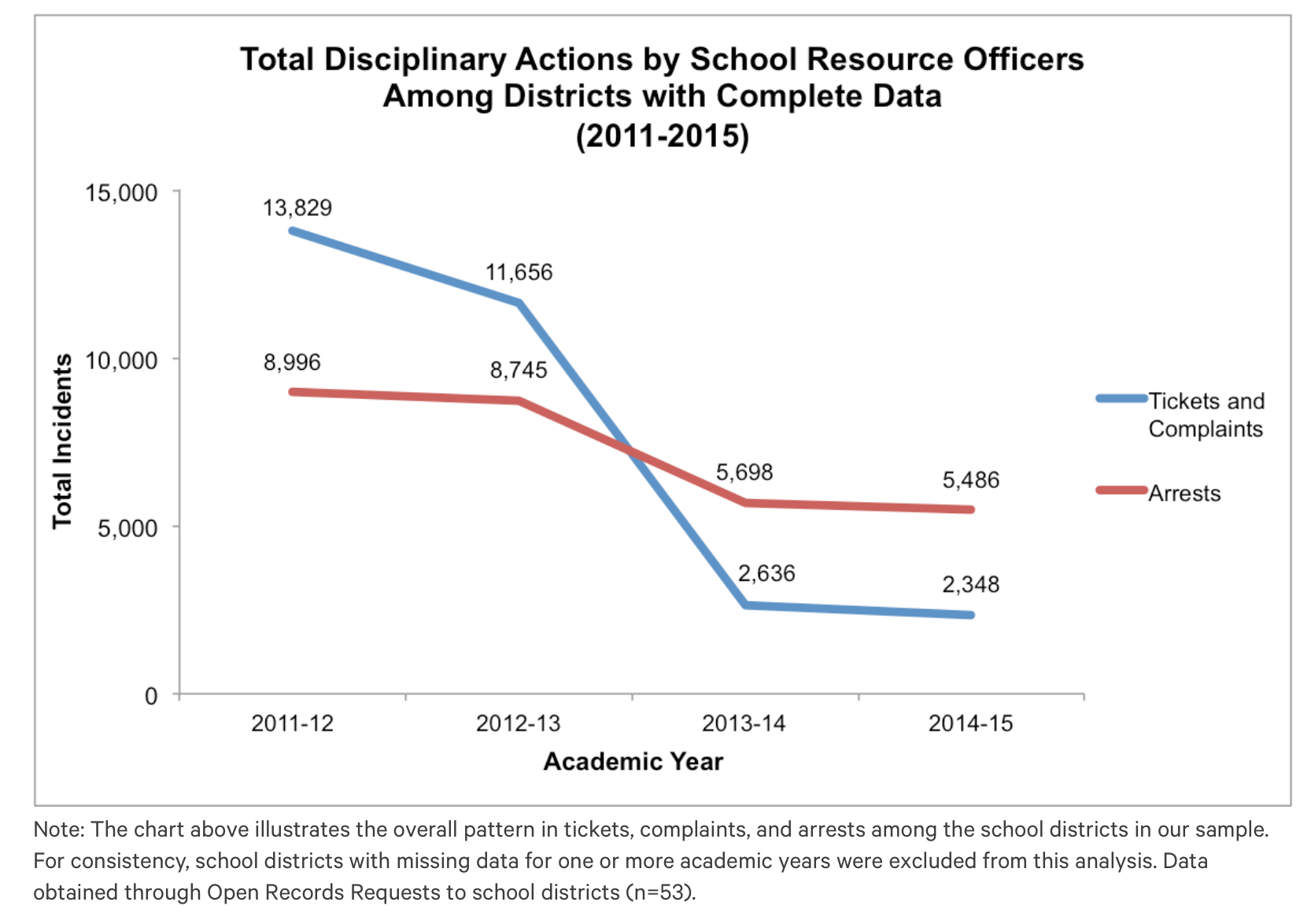

From 2011 to 2015, the number of tickets and complaints issued by school resource officers among the 53 districts with complete data went from almost 14,000 to roughly 2,300. Arrests saw a drop, though not as dramatic, as well, going from almost 9,000 to just under 5,500.

Several reforms are credited with the precipitous drop in ticketing, including the elimination of two of the most common offenses, "Disruption of Class" and "Disruption of Transportation," both Class C misdemeanors. The definitions for both were vague and could include things like "talking too much or making a noise in class," according to the report. Wright said they were issues that used to be resolved by a counselor or assistant principal. But over time, "school police officers were being called in instead," she said. "And it could range from repeatedly interrupting the instructor to fighting with another student to throwing spitballs. We heard stories that ran the entire gamut, the most innocuous to the really disruptive but usally nonviolent."

Since the reform, the report notes, Class C misdemeanor ticketing dropped more than 50 percent, mirroring a larger drop in juvenile crime. Still, almost 60,000 Class C misdemeanor cases were filed against juveniles across the state in 2015-2016, many stemming from school-based incidents. "After the law changed, it was mostly offenses that still tapped into classroom misbehavior that were just worded differently," explained Wright. Between the 2013-2014 school year and the 2014-2015 school year, the percentage of citations issued for "Disorderly Conduct," also a Class C misdemeanor, increased from 18 to 29 percent of all school-based complaints, according to the report.

Disorderly Conduct can include disruptive noises, inappropriate language or an offensive gesture. "When charged," the report reads, "they can be fined up to $500 plus court costs, and could have a criminal conviction on their record, impacting future school, job, and military opportunities." And because the misdemeanors are fine-only offenses, explained Lauren Rose, Director of Youth Justice Policy for Texans Care for Children, the students do not have the right to an attorney.

Even with the reforms, persistent disparities continued. "In every major component of the school-to-prison pipeline—classroom exclusions, police contact, probation referrals, and court contact—Black and, in many districts, Latino youth are over-represented," reads the report. The report also found that students receiving special education were overrepresented in the number of tickets, complaints, arrests and use of force incidents recorded in the districts that provided disaggregated data. Because there are few reporting requirements for school discipline, data can be hard to collect and analyze. Wright said there are regular efforts to pass legislation to improve data reporting but that they haven't made it far in recent sessions.

Being charged with a misdemeanor has serious consequences and costs for the students. And the entire school resource officer infrastructure is costly and growing more so as districts spend more each year on school police programs, the report argues. "We looked overall and we looked separately at small districts versus large and across the board, we’re seeing that spending per capita and spending overall is increasing year over year with 2014-2015 being the highest year over the last four," said Wright. Of the 53 districts that supplied budget data, the per student cost to support internal police departments was around $75. "It's going up despite the fact that there are fewer tickets being issued and generally less juvenile crime over the last five years," said Wright. "That was pretty striking because it suggests that need for SROs and the actual funding aren’t necessarily yoked."

The report offered several recommendations, including eliminating the criminal components of Class C misdemeanors for juveniles and getting rid of Disorderly Conduct altogether; better data collection on police in schools; increased youth training for officers in schools and steps to keep 10-12 year olds out of the juvenile justice system and prevent youth 17 years from being tried as adults. The report also highlighted alternatives to the use of police on campuses, including restorative justice programs and social and emotional learning.

"We need to rethink where we’re allocating our resources," said Wright. "It's not necessarily that school resource officers are the cause of the school-to-prison pipeline. They're just a component but right now they're a really expensive component and widespread component."