A middle-class African American family in Sugar Land might appear on the surface to live the same life as a similar family with a similar income in Pasadena or Houston. But in fact, the Sugar Land family is more likely to live in a neighborhood with lower poverty rates, higher homeownership rates, and a higher percentage of college-educated neighbors according to a recent study of American metropolitan areas by Deirdre Pfeiffer, a professor of urban planning at Arizona State University.

The study’s analysis is rooted in a national investigation of what Pfeiffer dubs “post-civil rights suburbs,” areas she defines as having more than 75% of housing stock built after 1975. These are usually second-ring suburbs that sit a distance from historic urban centers. The study contends that minority residents in these communities are surrounded by greater social and economic equity and more stable neighborhoods than minority Americans living in either older suburbs or the central cities.

This conclusion challenges the historically held notion that our metropolitan areas are split between successful suburbs and struggling cities. Her findings help pull apart our facile definition of suburbia, which too often envelops vastly different communities into one, overly simplified category. By carefully parsing and comparing different types of suburbs, Pfeiffer contributes to ongoing research about poverty, economic opportunity, and minority suburbanization, some of which my colleague, Heather O’Connell, discussed last week.

To Pfeiffer the age of a suburb’s housing stock signals the presence or absence of factors that help create equality. Because post-civil rights suburbs were built after the 1968 Fair Housing Act, they tend to be more racially integrated and ethnically diverse than older suburbs. They also come with fewer cognitive or physical demarcations tied to historic constructions of race that still shape housing markets in inner-ring suburbs and central cities. Moreover, residents in post-civil rights suburbs are more likely to have similar, and higher, income levels and higher homeownership rates, contributing to greater overall equity.

Pfeiffer holds post-civil rights suburbs aloft as crucial examples of successful minority suburbanization at a time when most anecdotal and demographic evidence is painting a dreary picture of the process.

The data for the study consists of the neighborhood rates for three economic indicators—poverty, college education, and homeownership—among white, black, Asian, and Latino households from all income levels in the nation’s 88 largest regions. Pfeiffer then compares indicators for minority neighborhood conditions to those of whites in each of three geographic areas—central city, older suburbs, and post-civil rights suburbs.

Zooming in on Houston highlights the study’s conclusions.

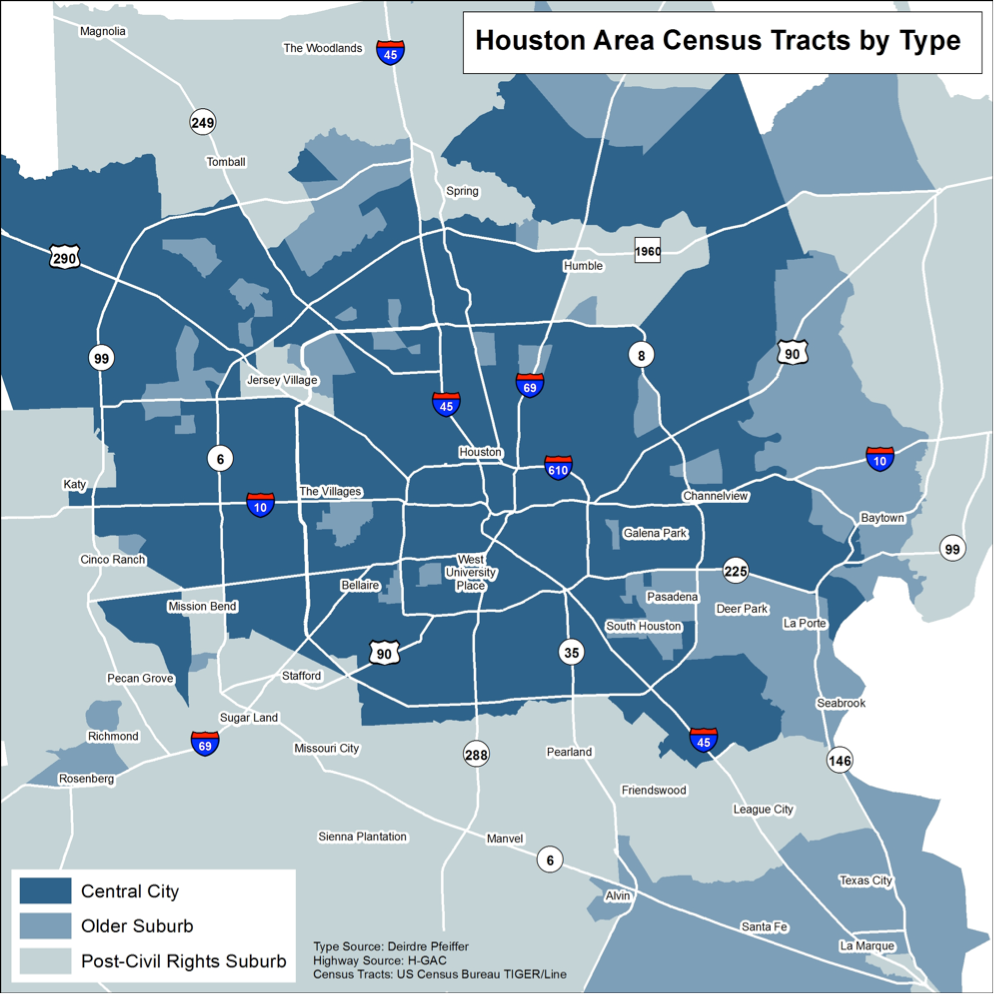

This map categorizes each Houston-area census tract as either part of the central city, an older suburb, or as a post-civil rights suburb. Again, if 75% of a non-central city tract’s housing was built after 1975, it was classified as a post-civil rights suburb.

For the most part the image offers few surprises. Pasadena and La Porte are classified as older suburbs. Katy and the Woodlands are defined as post-civil rights suburbs. Where the map gets interesting is in places like Jersey Village, where some tracts qualify as post-civil rights and others do not. This marks a quirk of Houston’s development chronology, but also suggests that minorities living one census tract away from each other may face very different neighborhood conditions. Also worth tracking are older suburbs, like Rosenberg, which mix old housing stock with major new housing developments.

Overall, the Houston region presents a compelling example of Pfeiffer’s main findings that post-civil rights suburbs are the most beneficial for low-income Americans and African Americans of all incomes. Houston bears these two results out and also captures the significantly positive effect that living in post-civil rights suburbs can have for Latinos as well.

The study shows that post-civil rights suburbs offer greater racial equity than the central city or older suburbs across all three economic indicators, income levels, and time period for both African American and Latino Houstonians.

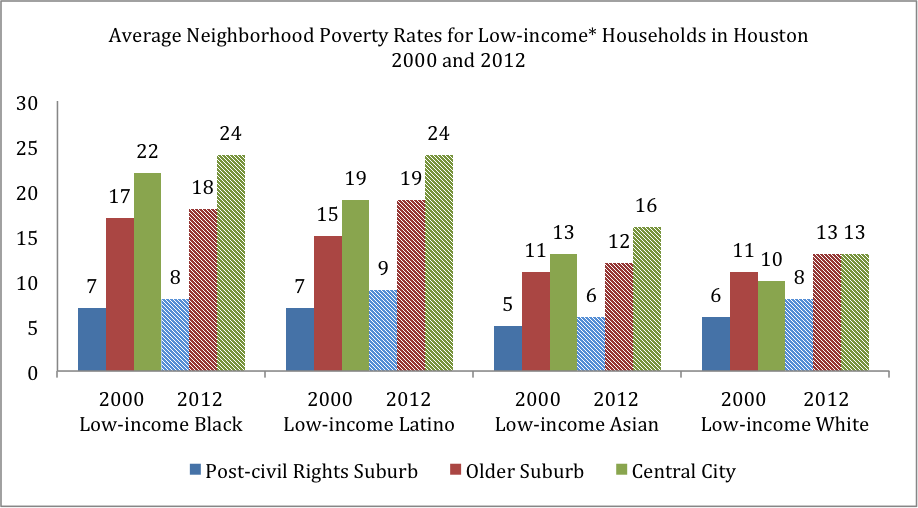

Low-income Houstonians of all races also face significantly better neighborhood prospects if they live in post-civil rights suburbs. Comparing the positions of these groups across the three geographies in Houston between 2000-2012 shows how dramatic the difference is.

In terms of poverty rate low-income households in post-civil rights suburbs are in neighborhoods with lower rates than those in the central city, and perhaps more surprising, much lower than those in older suburbs as well. This held true across the great recession, even as poverty levels grew in each geography, indicating the durability of the trend.

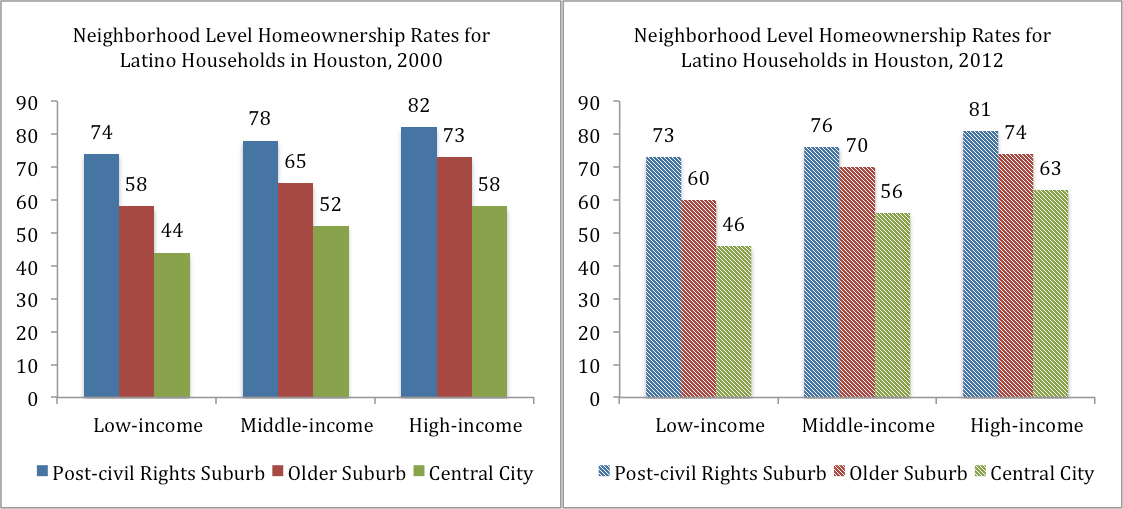

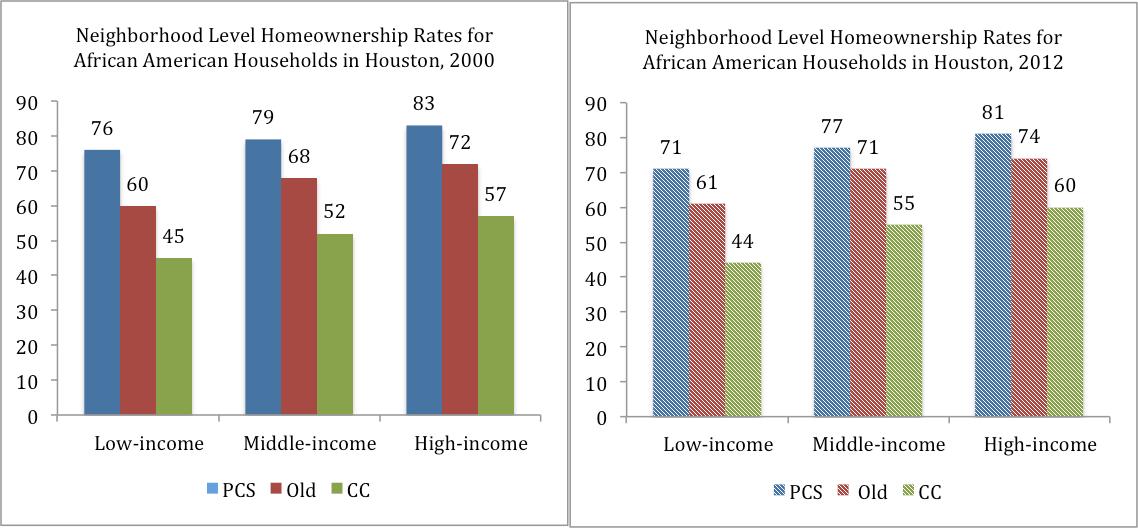

The benefits of living in a post-civil rights suburb do not stop with low income Houstonians. The homeownership rates in neighborhoods around African American and Latino households of all income levels show some striking differences when compared across the three geographies as well.

These charts show that African American and Latino households in post-civil rights suburbs are surrounded by a larger percentage of homeowners than their counterparts in the other two geographies. The gap is largest when comparing neighborhood homeownership rates of post-civil rights suburbs and the central city, where renters are often on par with homeowners. Those living in post-civil rights suburbs are more likely to be surrounded by homeowners, which, in turn, suggests again that they live in more stable communities.

Interestingly, though, the neighborhood rate of ownership in post-civil rights suburbs for both racial groups fell between 2000 and 2012. At the same time, homeownership rates in the older suburbs grew. This suggests that more black and Latino residents are buying homes in the very neighborhoods that Pfeiffer is arguing offer fewer opportunities. It is also the opposite of what is happening for white Houstonians, who are seeing increases in neighborhood level homeownership rates in post-civil rights suburbs and declines in older suburbs. If such long-term trends continue, the likelihood of suburban minority poverty concentrating in older suburbs increases.

Pfeiffer’s findings should push us to consider why older suburbs and the central city are so far behind post-civil rights suburbs across these indicators. Further, we might ask how the success of post-civil rights suburbs could be replicated in other areas.

Pfeiffer draws some problematic conclusions about future residential development in American metro areas. She argues that her findings make a compelling case for the continued development of outer-ring suburbs that offer cheaper home values and encourage more multi-ethnic suburbs.

This is a knotty conclusion for a number of reasons. First, unabated outward residential growth would exacerbate problems with transportation and service provision in already spread-out regions such as Houston. Second, encouraging continued outward growth, while failing to address entrenched inequalities within the central city and inner-ring suburbs is not politically or economically sustainable. Spreading scant public resources further afield cannot solve existing problems.

Houston’s booming housing market and the strong economic position of the metropolitan area present valuable opportunities both to experiment with Pfeiffer’s findings and to test alternatives to outward growth. The metropolitan region is experiencing both rapid suburban growth and significant levels of infill. Each of these trends will lead to shifts in neighborhood conditions, with the central city facing the most intense transitions as wealthier residents move into formerly lower-income or racially segregated areas. Houston could recreate some of the strengths of post-civil rights suburbs in other parts of town by embracing policies that require the building of affordable housing units and help create more mixed-income neighborhoods. Otherwise, the infill of wealthier Houstonians might push minorities and lower-income Houstonians into to older suburbs and shift the neighborhood-level challenges with them.