This post has been updated.

Jennifer Mann was in the middle of a conversation with a student about his behavior. As a principal at Wharton Elementary School and with 30-some years of experience in education, she had had this kind of discussion before. But then it started to rain.

The student panicked, remembered Mann. "I have to call my mom now," he told her. "It's raining, I have to call my mom."

After Hurricane Harvey hit and devastated the small town of Wharton, Texas about an hour southwest of Houston's downtown, Mann said situations like that have become part of the norm, as teachers and students cope with the lingering effects of the storm. Every time it rains, Mann said at a panel discussion hosted by the Texas Tribune Tuesday, there's crying, parents wanting to pick kids up and more signs of the storm's trauma.

Then there are the more concrete impacts: 200 students that left the district.Ten days of missed classes and make-up after-school sessions to make sure students at the school, which serves third through sixth grade, will be ready for the tests. And one social worker, which Mann was finally able to hire in April, months after the storm hit, when money she applied for from the state finally came through.

"I really feel like we were kind of forgotten about by the state," said Mann.

She isn't alone. Representatives from other Houston-area districts talked Tuesday about the lasting impact of Harvey, just days after the start of a new hurricane season on June 1. In the Houston Independent School District, for example, students at seven schools had to start the school year in nearby vacant buildings or neighboring campuses because of damage from the storm. The district scrambled to provide free breakfasts and lunch for all students, as well as uniforms. And campuses across the area worked to react to needs of students and teachers. In Conroe ISD, for example, the number of homeless students doubled this school year, just shy of 1,000. According to a November survey by KHOU, some 2,734 students in Katy ISD, 2,562 in Houston ISD and 2,063 in Pasadena ISD were left homeless after the storm.

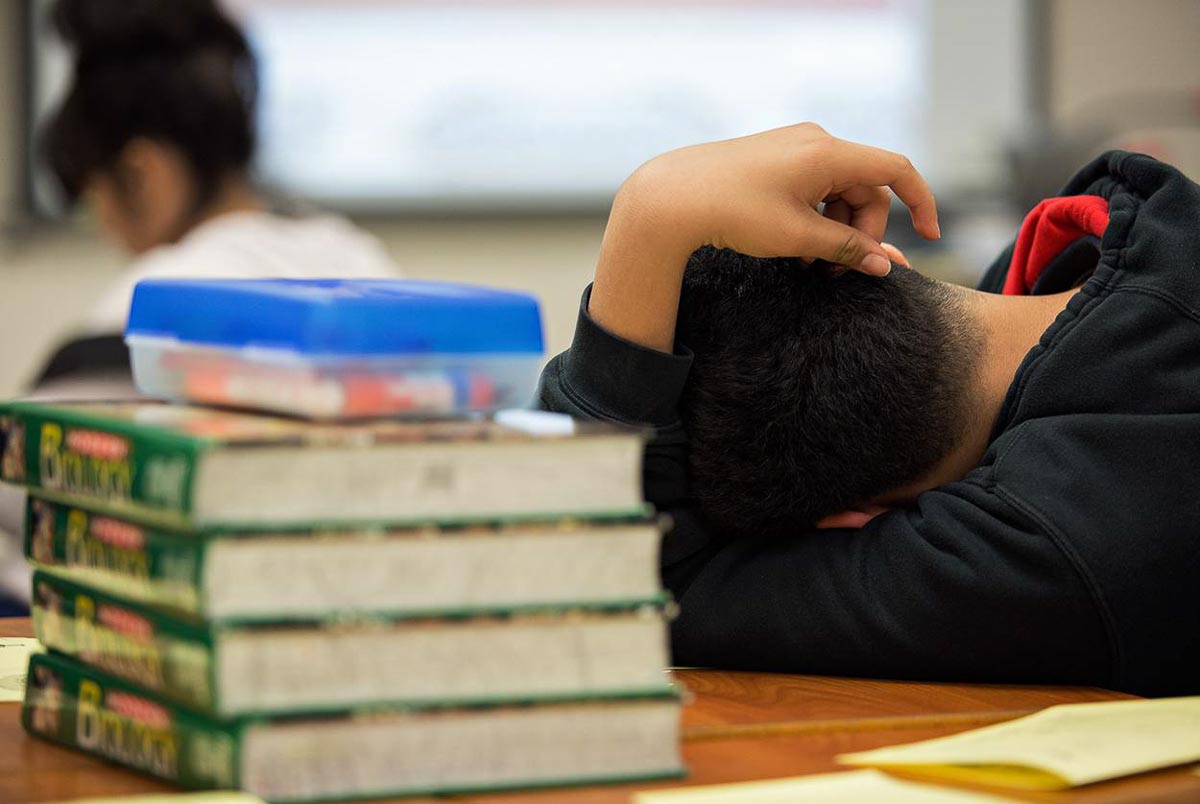

"If you don't have what you need on a day to day basis, you're not as concerned about education...because that's not an immediate need," said Tiffany Robinson, a secondary science instructional specialist at the Elsik Ninth Grade Center. "That was definitely a challenge we felt this year more than any other year."

Still, social worker Rhonda Howard, who works at Houston ISD's T.H. Rogers School said, "The children are resilient if they have the supports and the teachers there."

But teachers were often affected too. "I took on a lot of responsibilities and roles I didn't expect to take on," said Anh-Minh Nguyen, who graduated from Alief ISD's Early College High School this year and who said absent teachers and staff meant he had to scramble for recommendation letters for college applications and help lead his debate team through the year. Though his home only sustained roof damage from the storm, Nguyen said he spent many calls on the phone with insurance agents.

Immediately following the storm, educators, some of whom were also dealing with damaged or flooded homes, had to make tough decisions. With 11 days of school missed, campuses had to adjust the curriculum for the year, cutting out things like field trips and multi-day class projects in favor of material that would show up on state tests. At Alief ISD, Robinson said they had to have students to stay after school for tutoring. And for students who couldn't stay late, she said, they had to pull them out of gym or art. "I hated doing that," said Robinson.

The balance act she and others described was an impossible one; with the emotional and sometimes basic needs of students and teachers on the one hand and the pressure of tests on the other.

Because Mann's campus serves third through sixth grade, that means every grade takes state tests at the end of the year. "Our level of anxiety was very high," she said. They also implemented after-school tutorials, disguised as "camps" and meant to be fun. Though 10 missed days might not sound like much, she said, "for schools like ours--we're a Title I school--where we're already a little behind the eight ball to being with, it really took a toll." Reflecting on the long and still ongoing recovery process Tuesday she said, "I am concerned about the testing, that was such a focus."

The state dealyed deciding whether those scores will figure into annual accountability ratings until Wednesday when it announced that schools meeting one of four criteria would be exempted. Schools had to either be closed for at least 10 days, have at least 10 percent of the its students homeless or displaced to another school as a result of the storm, have at least 10 percent of its teachers homeless or have been forced to send its students to another campus or shared space through the winter break.

As schools look to the summer and the next school year, the impact of Harvey is likely to remain. "I have one counselor and believe me she is a busy woman," said Mann, who said her goal now is to secure more funding to support the needs of students and staff.

"He thinks it's going to flood again," she remembered thinking about the student panicked in her office about the rain. "It broke my heart."