“Movement is a privilege today, not a right,” Tsay said, speaking to a virtual audience for the Kinder Institute Forum on March 23. “And I think this is something that I've really focused on for all of my time—my professional life—is just this belief: It doesn't have to be that way.”

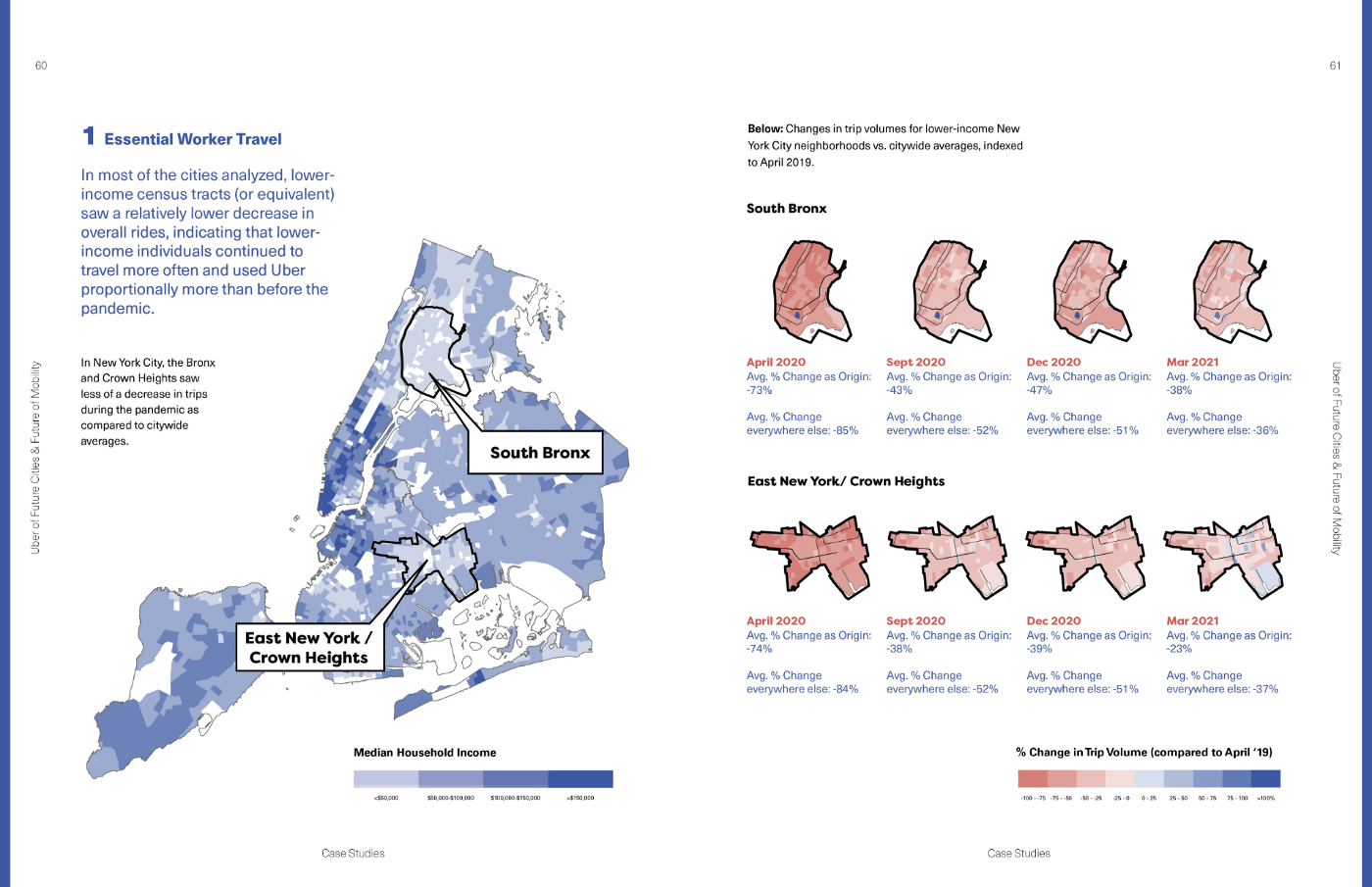

One of the lessons that the pandemic drove home for Uber was that the platform was serving as a kind of “mobility insurance”—a ride of last resort when other options do not exist or are inaccessible. Ridership data from April 2020 to March 2021 suggested that rides in lower income Census tracts in New York City did not drop off as much as it did for higher-income areas. (This lines up with other research as well. A study of Lyft rides in Austin found that lower-income neighborhoods use ride-hailing services slightly more than their middle-income counterparts, despite having similar rates of car ownership.)

“It's not to say they use it more, it's to say that they may be dependent on it in ways that we don't really give people enough visibility into,” Tsay said.

The rides seem to fill a role when other options aren’t available, such as when a rainstorm makes bike travel difficult or when transit services are disrupted, like they were during the pandemic.

“There were a lot of rides to parks,” she said. “And there were a lot of rides to Staten Island, a place where there are a lot of warehouses. So maybe there were a lot of workers getting to work just when the … MTA had to cut service.”

Ride-hailing is convenient, but it’s not exactly cheap. (A Goldman Sachs analysis found ride-hailing costs around $2.50 per mile on average.) As it did in so many other areas, the pandemic highlighted the privilege of mobility.

“Transportation is inequitable based on cost—the lowest-income households bear the greatest burden disproportionately. And it's also inequitable based on time,” Tsay said. “And we know also that in spite of all these inequities that we can't go on continuing doing things the way that we have been doing.”

Tsay said Uber’s is experimenting with partners to work on closing some of these equity gaps by targeting high-need populations. In one program, the company is working with the Surgo Foundation to provide rides for expecting mothers in Washington, D.C., so that they can attend prenatal care appointments. In another program in Cecil County, Maryland, the company is helping residents of addiction recovery houses meet their doctors’ appointments and attend job interviews, with encouraging results.

‘“I just think that, of course, it's no surprise that getting a giving a ride to someone who is in need and trying to take care of other parts of their lives helps them, but it's not necessarily the way that we're structured to do things,” she said.

The company also partners with some transit agencies to include bus and train trip planning, as well as micromobility options such as scooters and e-bikes. Uber is also encouraging taxi and other ride companies in smaller cities to get on its platform to increase utilization. (A company goal is to get all taxi drivers on the app by 2025.)

Clearly ride-hailing has become a key part of the urban transportation mix, and Tsay said Uber is trying to make sustainable options—such as opting to ride in an EV or use a scooter instead of a car—more accessible.

“These modes are interdependent,” she said. “If you look at national travel data … households with cars will always have a greater and stronger preference for taking their car. And once you take your car out of the house, you're stuck with a car all day long for every trip. But if you can have all the options at your fingertips, you are much more able to leave the house and catch a bus or take a bike.”

In other words, making transit more appealing and accessible also means greater opportunities for ride-hailing to fill the gaps.

The interesting opportunity for Uber, which accounts for 70% of the ride-hailing market in the US (Lyft has about 30%), is the ability to rapidly roll out changes that impact the transit ecosystem more broadly. With some effort, the firm can take pilot programs and scale them up across dozens of cities and thousands of drivers. Tsay's focus, however, is on bringing non-government organizations as well as policymakers to the table.

“What we're seeing is that you need to bring all of these different pieces together, in order to make the change that we would like to see,” she said.

In London, for example, the company’s clean air and equity goals aligned with public policy. There, the company established a funding mechanism to help drivers in London acquire electric vehicles so that they can provide service in the city’s low-emission zones. It’s also helping to install electric charging stations in low-income neighborhoods.

“Ride-hail electrification has to be equitable. The people earning on gig platforms are primarily low income and people of color. And so it's really important that we're thinking about ways of supporting that transition fairly,” Tsay said.

But even with seemingly grand scale, its effect can be limited. Tsay acknowledges that the vast majority of trips are through privately owned vehicles, and this is expected to be the case for the foreseeable future. As big as ride-hailing is, Uber’s own investor report indicates that it has a market penetration of just 4% of the population in the US. And Goldman Sach’s “Future of Mobility” report notes that ride-hailing is more a luxury than a utility for most people, especially as ride costs increase as venture capital subsidies recede.

Tsay acknowledges the elephant in the (virtual) room: Isn’t the solution fewer cars?

“Don't you remember this principle of moving people, not vehicles?” Tsay asks herself for the benefit of the audience. That is important, she said, but she recalled a comment by the Revs. Robert Ennis Jackson and DeVanie Jackson, community partners in Brooklyn she worked with as an advocate for pedestrians and bicycle riders. “At some point, you know, both reverends just said to me, ‘Shin-pei, do you know what it's like for a black man to be running down the street, what that looks like? We need things today. We can't wait for conditions to change for us to be able to walk and bike safely.’ … And that really stuck with me as I went and tried lots of different initiatives to continue to work on: ‘How do we increase access for people with this with great urgency to meet the needs of today, and to not expect people to wait for something to come along?’”

Watch the full Kinder Institute Forum presentation below.