Within a year of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans schools found themselves in the midst of an unprecedented moment in American education.

All public school employees were fired. The existing teacher contract was tossed, as were existing district lines. The state took over initially, but soon it turned nearly every school into an independent charter.

“New Orleans essentially erased its traditional school district and started over,” writes Douglas N. Harris, a Tulane University professor and author of a new study on the results of the dramatic changes. “In the process, the city has provided the first direct test of an alternative to the system that has dominated American public education for more than a century.”

The system has been touted by reform-minded politicians, Harris writes, but it also legitimately provided what they’d for years yearned to know: if you gave schools encouragement to innovate, and freed them from union and district rules, would they live up to the reform hype?

The results have been astounding, but there’s reason to hesitate before assuming they’d work countrywide. Harris and fellow researchers at Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans recently published three studies examining the reforms.

Before the Storm

New Orleans schools before the storm were racked with dysfunction and malfeasance. Financial scandals led the district to hire eight superintendents in as many years.

The student body was overwhelmingly poor, with 83 percent of students eligible for free school lunch, and the district ranked second to last in the state in reading and math scores. The graduation rate was well below the state average.

The Study and Findings

Researchers recognized that the dramatic before-and-after changes in New Orleans schools offered incomparable conditions for an experiment.

They sought to measure the difference in school performance between the traditional system and the post-Katrina reorganization. But they knew this wouldn’t be a sufficient experiment, given the possibility that other factors may explain any improvements.

“This calls for making the same before-and-after comparison in a group that is identical, except for being unaffected by the treatment,” Harris writes.

So his team controlled for the effects of New Orleans’ reforms in two ways.

In one study, the researchers looked only at the students who returned to the city after the storm, giving them a chance to study the same group of students over a period spanning reform implementation.

They also broke students into groups – such as third graders in 2005 and third graders in 2012 – to get a picture of how similar cohorts performed before and after the storm.

In both cases, researchers compared the results of New Orleans students with those in other Louisiana districts, which didn’t undergo the same reforms.

The results were significant.

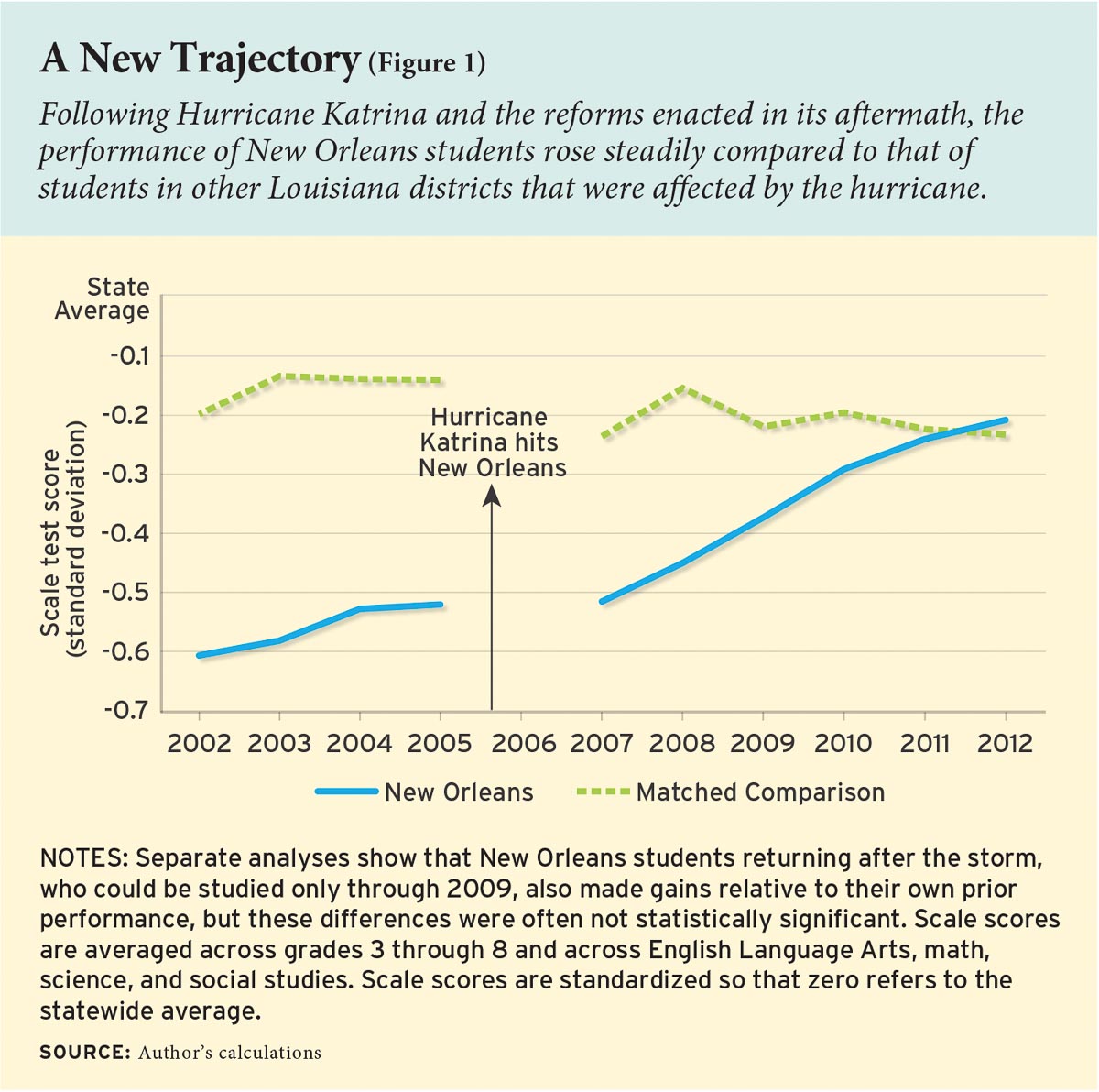

“The performance of New Orleans students shot upward after the reforms. In contrast, the comparison group” – in other words, other Louisiana students – “largely continued its prior trajectory,” Harris writes.

Before the reforms, New Orleans students performed far below state averages, while they and students elsewhere in Louisiana saw their performance generally trending in the same direction.

Not only did New Orleans schools close the performance gap with other districts, they reversed it.

Despite his efforts to control for the effects of school reform, Harris nonetheless cautions sweeping conclusions.

Changes in the city’s population and demographics before and after the storm could account for some of the improvement. But the effects from other possible factors – especially “teaching to the test,” since charters could be shut down based on reading and math scores – appear relatively small, according to the study.

The research examined whether the average improvements obscured any inequitable outcomes. Importantly, the researchers wanted to know if kids from certain minority groups or lower-income families didn’t get the same bump.

Those results were a little more nuanced but still showed promise.

“(I)t would be hard to say the outcomes from the New Orleans reforms are inequitable relative to what came before them,” Harris writes, acknowledging there’s still room for improvement.

So what changed, specifically? In large part, it was the freedom for principals to make personnel decisions. They could hire anyone they wanted, and they could fire them nearly as easily.

The number of teachers with traditional certifications, as well as those with at least 20 years of experience, both dropped by about 20 percent. Overall the teacher turnover rate nearly doubled. Teachers were increasingly uncertified, coming from programs like Teach for America and The New Teacher Project.

“The fact that such large improvements in student learning could be achieved with these common metrics going in the ‘wrong direction’ reinforces a common finding in education research: teacher credentials and turnover are not always good barometers of effectiveness,” Harris writes.

The reforms also brought increased school funding. Per student school expenditures increased by $1,000, relative to other state districts.

The Implications

Test scores for New Orleans students improved by between 8 percent and 15 percent after the reforms.

“We are not aware of any other districts that have made such large improvements in such a short time,” Harris writes.

Yet he says there’s good reason to doubt the New Orleans experiment could be replicated elsewhere.

The prior system was so bad, test scores had nowhere to go but up. Meanwhile, New Orleans after the storm was a magnet for eager young adults looking to help.

Even replicating the process on a state level might not be possible, due to limitations in the availability of such teachers.

“It seems difficult enough attracting effective teachers and leaders to work long hours at modest salaries in New Orleans; doing it throughout Louisiana is unrealistic without a major change in the educator labor market,” Harris writes.

Nonetheless, the results are so stark, they can’t be disregarded, the researchers conclude.

“The city’s reforms force us to question basic assumptions about what K‒12 publicly funded education can and should look like,” Harris writes.

Good News for New Orleans | Douglas N. Harris and researchers from the Education Research Alliance for New Orleans at Tulane University.