From the hills behind the City Hall in my adopted hometown of Ventura, California, it’s less than 1,000 yards southward to the Pacific Ocean. This constrained piece of topography creates a small urban gem of a downtown: streetscapes, restaurants, stores, offices, residences, parking garages and a beachfront promenade, all within eight or so square blocks, creating a lively street life that connects a historic downtown to the beach.

But this narrow slot is also a critical part of California’s coastal transportation corridor. Laced throughout the thousand yards are five local streets; the Union Pacific Coast Line, which also carries Amtrak trains; and U.S. Highway 101, the Ventura Highway, which carries 100,000 cars and trucks a day through downtown Ventura. Without this slot, it would be simply impossible to traverse the California coast; the nearest alternative freeway route, I-5, is 45 miles inland. (Like many places in Southern California, Ventura has a south-facing beach, so the slot is situated east-west, even though people going through it are traveling north toward San Francisco or south toward Los Angeles.)

At its widest point, this transportation corridor chews up almost 300 of the 1,000 yards between the hills and the beach. In the mile or so that the freeway and the rail line straddle downtown, there are only three places to cross it. To the west is an underpass near the Ventura County Fairgrounds, a harsh crossing but one that is softened by the Tortilla Flats mural, commemorating the Latino neighborhood that got wiped out by the freeway. To the east is a pedestrian overpass that connects the edge of downtown to the historic Ventura Pier. In the middle—the most frequently used connection—is a small walkway along California Street above the freeway. To get from downtown to the beach, you have to brave the freeway noise and then cross the rail line at grade.

It’s an unpleasant experience. But it’s one that’s typical in every American city.

In almost every urban location I have ever lived, a midcentury transportation scar stretches across the landscape and makes navigation difficult for pedestrians. As I have written elsewhere, my hometown of Auburn, New York, suffered two scars: a downtown “Loop Road” and an arterial highway two blocks away. When I first moved to Los Angeles, I lived on the border of West L.A. and Santa Monica, four doors away from the Santa Monica Freeway (I-10), under which I had to walk to access all of my daily errands. In San Diego, my apartment overlooked I-5, whose offramps I had to cross in order to get to work. And in midtown Houston, where I now live, this supposedly walkable neighborhood—often touted as the city’s most urban place—is laced with six fast-moving, one-way streets that connect Texas 527 with downtown and other freeways. (Mayor Sylvester Turner recently reinforced this pattern by overturning his own public works director and deciding to rebuild, rather than close, two of these streets.)

Much has been written about how these highways have destroyed neighborhoods—especially African American neighborhoods—and divided our cities, including this fine piece about I-45 in Houston by my Kinder Institute colleague Kyle Shelton, author of Power Moves. The complicated truth is that even as these freeways destroyed and divided neighborhoods, they also provided regional access to downtowns and other central-city locations that were struggling in the postwar suburban era. And in recent years, they may have helped the rebirth of urban neighborhoods by giving city residents easy driving access to suburban job centers and also giving shoppers easy access to historic Main Streets. For most people under the age of 60, urban freeways are just a fact of life, simply accepted and rarely thought about.

But as I have delved into the impact of the urban highway on my own hometown of Auburn, I have been astonished at the deep reservoir of emotion many people still feel about the impact that these transportation projects have had not just on our landscape, but on people’s lives, families and businesses. Consider, for example, the story of Conaty’s Seafood in Auburn: This venerable family-owned business was taken for a highway by eminent domain in 1974, and the patriarch died of a heart attack as a result. A half-century later, the family still struggles with the emotional fallout.

This family tragedy was repeated over and over again in urban neighborhoods all over the country. There’s no question, for example, that urban highways have harmed African American neighborhoods and impeded their ability to accumulate wealth through homeownership. They also tore apart urban business districts, especially—once again—in African American neighborhoods.

But, like most things that are around for a half a century, urban highways are now undergoing what might be called a “Big Rethink.” Many urban freeway expansion projects around the country—like I-45 in Houston—are being questioned and challenged as never before. In large part, this is because of the renewed understanding of how public policy decisions have sustained systemic racism over time. But it’s also simply a recognition that, however convenient urban freeways are for many people, it’s possible to repair the damage to our urban fabric and the daily lives of people who live in city neighborhoods. And in many cases, it can be done without sacrificing mobility.

So, it’s not surprising that President Biden’s new transportation secretary—Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of a small Rust Belt city—has called attention to the need to heal urban freeway scars. “Black and brown neighborhoods have been disproportionately divided by highway projects or left isolated by the lack of adequate transit and transportation resources,” Buttigieg recently tweeted. And the Senate is considering a $10 billion pilot program to tear down urban highways.

Make no mistake: Undoing the midcentury scars of urban freeways is an extremely expensive proposition. No doubt $10 billion is a tiny down payment. Boston’s “Big Dig”—which helped heal the urban freeway scars in that city by burying the Central Artery through the center of the city—cost almost that much all by itself. There’s not enough gas tax in the world to pay for all that needs to be done. So, we’ll have to be creative on financing—and opportunistic about where to start.

The gold standard for healing remains the Embarcadero in San Francisco, a great example of an opportunistic approach. This roadway runs along the waterfront, connecting downtown San Francisco to the city’s piers. Built on reclaimed land, it dates back more than a century. In the 1950s, city and state leaders began building an elevated freeway along the route, designed to connect the Bay Bridge to the Golden Gate Bridge, but the Embarcadero became the subject of the first great freeway fight in the U.S. and was never completed. In 1989, it collapsed during the Loma Prieta earthquake.

The Embarcadero was rebuilt not as a freeway, but as a beautiful boulevard. And while the piers no longer serve their original purpose, the boulevard has revitalized the entire area. Pedestrians and joggers can be found everywhere, and most striking is the way the boulevard reconnected the Ferry Building to Market Street, making the building (which is still a transportation hub) a beehive of retail activity.

As many of our urban freeways reach the point where they need rebuilding, the idea of removing a freeway structure and replacing it with a boulevard is growing in popularity—especially if there are alternative routes for freeway traffic. One of the most interesting proposals currently is the “Community Grid” that would replace the elevated I-81 through downtown Syracuse, New York, 25 miles from where I grew up, with a boulevard.

I-81 is a classic urban scar, dividing downtown Syracuse from the adjacent University Hill (where Syracuse University is located) and then plowing through a historically African American neighborhood. But now that I-481 serves as a bypass around the city, the I-81 structure is not needed for intercity travel. The Community Grid proposal would be a tree-lined boulevard that would sew the city back together, and it’s considered a prime candidate for the Buttigieg approach to urban transportation.

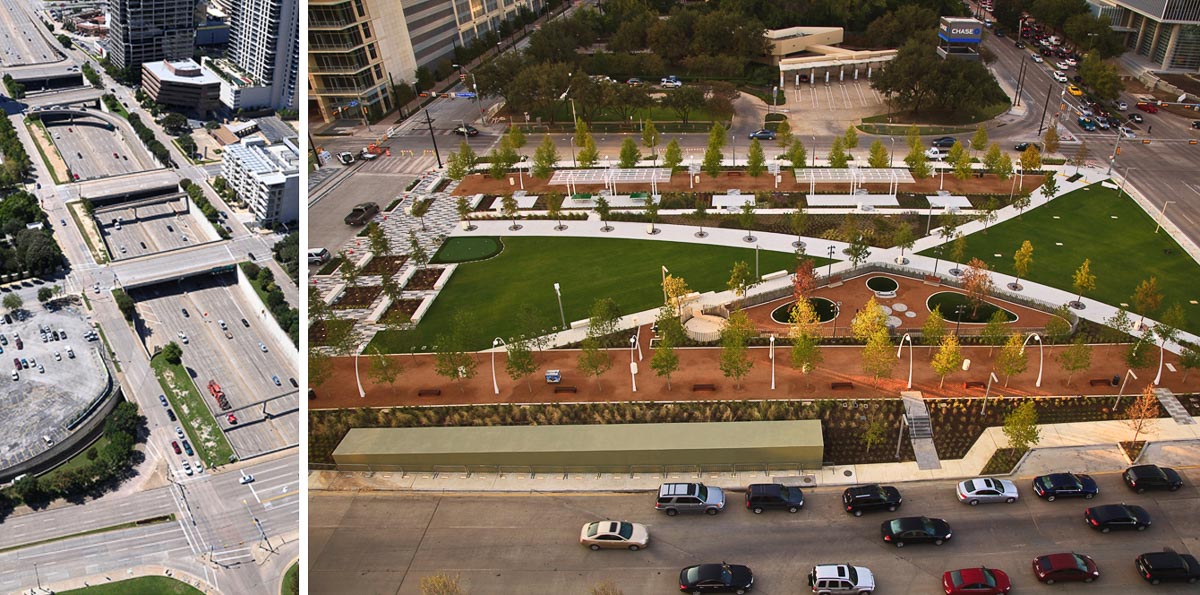

Of course, not all urban freeways are elevated structures. Some are below ground, in trenches, which creates a different kind of opportunity, the ability to simply place a deck above the freeway to reconnect the city. Maybe the most prominent example is Klyde Warren Park, which covers three blocks of TX-366 in the heart of downtown Dallas. Other than the Embarcadero, I know of no urban freeway recovery project that has had such a dramatic effect on a city. Like the Embarcadero, Klyde Warren Park is a hive of human activity, featuring not only businesses like restaurants but also open space that anyone can enjoy. There’s a separate civic entity devoted to programming the park’s activities.

Before and after photos of Klyde Warren Park in Dallas.

But financing freeway caps isn’t easy. Whereas old freeway structures need new public investment to be rebuilt or torn down, there’s no real transportation reason to put a deck over a freeway trench. So, funding has to come from multiple sources. In the case of Klyde Warren Park, which cost $110 million, about half the funds came from public sources—TxDOT, City of Dallas bonds and Great Recession–era federal stimulus money—while the other half came from private donations. The biggest donor ($10 million) was energy billionaire Kelcy Warren, and the park is named for his young son.

Another way to fund freeway decks is to take financial advantage of the fact that by building a deck, you’re creating valuable urban real estate. This is how Washington, D.C., approached Capitol Crossing, a three-block deck over I-395 just north of the National Mall. Capitol Crossing heals a big scar on the east side of the city’s rapidly developing downtown, but it does so at something of a price. Instead of spending public dollars on the cap, the city sold the land beneath the highway directly to a private real estate company, which then had to maximize leasable square footage in order to make the deal work. As a result, although the gap has been covered, there’s not much public space in the final product.

Boston’s “Big Dig”—which helped heal the urban freeway scars in that city by burying the Central Artery through the center of the city—cost almost $10 billion.

Photo source: Wikimedia Commons

Maybe the most controversial urban freeway project in the U.S. right now is the I-45 expansion in Houston, less than a mile from my house. It’s certainly one of the biggest—$7 billion, according to current estimates. The project has passionate advocates and a lot of good things about it, some of which can heal urban scars: decommissioning one stretch of elevated highway, dropping another into a trench with decks, and building a seven-block deck reconnecting downtown Houston to the rapidly revitalizing EADO (East downtown) area. But the project—technically known as the North Houston Highway Improvement Project—also calls for a significant expansion of the freeway’s footprint, including additional lanes and frontage roads. It will therefore create new scars, including cutting into a proud African American neighborhood that has already lost many homes to previous highway projects and taking out a strip of businesses in the very EADO neighborhood that will be reconnected to downtown by the seven-block freeway deck.

The I-45 project shows how difficult it is to simultaneously heal urban scars and expand an urban highway’s footprint. And maybe part of the Big Rethink is to question whether doing so is possible at all. But while it may be difficult to expand highway capacity while sewing cities back together, it’s more than possible to do so while maintaining the current capacity of urban transportation networks. In part that’s because urban highway projects have been ridiculously over-engineered over the years.

Take Highway 101 through downtown Los Angeles, near Union Station, where the possibility of a four-block deck park is currently being studied. This is one of several freeway decks being studied in Southern California, including three on Highway 101 alone.

Sure, Highway 101 through downtown L.A. is congested much of the time. (It carries about 200,000 cars a day.) But it’s also in a trench and hemmed in by urban development on both sides, so expansion isn’t possible. And, typical of 1950s freeway design, it includes almost a dozen on- and off-ramps in a mile-long stretch of highway. By removing unneeded ramps, the freeway deck project can reclaim some of the most valuable urban real estate in the country and create a park that knits downtown back together.

Almost 70 miles northwest of downtown L.A., also along Highway 101, is the narrow slot in downtown Ventura that I described earlier. Yes, the transportation corridor that runs through the slot is wide and disruptive. But, in typical over-engineered fashion, it includes a beautiful on-ramp that commands a sweeping Pacific Ocean view as it towers over both the freeway and the Union Pacific rail line. (You can see this onramp in the movie Little Miss Sunshine.) It is a spectacular structure by any measure. But that doesn’t mean only drivers should enjoy it.

Not long ago, the City of Ventura and the Southern California Association of Governments jointly sponsored a plan by RNT Architects to do the Big Rethink of Highway 101 in downtown Ventura. The plan proposed capping the freeway, reclaiming valuable urban land and extending downtown’s grid toward the beach. But it also contained a big idea: Decommission the on-ramp and turn it into a promenade connecting downtown and the beach. In other words, use the spectacular part of the mid-century scar to help create a 21st-century gem.

It’s hard to know whether the RNT plan—or some variation of it—will ever be built. Healing urban scars and reclaiming the urban environment comes with a steep price tag—and doesn’t always expand freeway capacity, which is usually the primary driver of state and federal transportation funding. But like the Embarcadero, Klyde Warren Park, the proposed I-81 Community Grid in Syracuse and the other proposed freeway caps in Southern California, the downtown Ventura plan does show that it’s possible to reclaim and heal America’s great urban landscapes. Let’s hope Secretary Buttigieg acts on his promise to do so.

This essay originally appeared on the Common Edge, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reconnecting architecture and design with the public that it’s meant to serve.