Los Angeles sound artist Alan Nakagawa has spent time in two worlds: government and art, with a longtime career as the arts administrator for the city's Metro and an education in public art. So when the city's Department of Transportation needed an artist to help communicate its ambitious, data-driven Vision Zero initiative, Nakagawa was an obvious fit for the first artist in residence with the department, coordinated through the city's cultural affairs office. Nakagawa just completed his year-long stint and talked with the Urban Edge to reflect back on the experience in an interview that has been edited for length and clarity.

You're still wrapping up the Mar Vista Great Streets project, which includes poetry, perfume and a newly published zine. How did that evolve?

The Great Streets project was ginormous, there was already a bike lane but they isolated the bike lane, the left turn lane became a light in some areas, they did a more robust pedestrian walkway, added signals.

There is a pretty robust artist community in the area, especially writers and poets, so I thought this is perfect for the haiku project. We got 32 haikus about traffic safety and pedestrian rights. I asked a couple of friends of mine, poets I've wanted to work with, they donated a haiku. So we had 36 and magically there happened to be 18 bike lane signs already installed.

Some entries from visual artists were incoproated into the zine, and that’s being distributed through the Vision Zero program, and the last part is the perfumes.

Tell me about the perfumes.

I started taking perfume lessons at a perfume lab in Chinatown, it’s a nonprofit arts organization called the Institute for Art and Olfaction. It's so much fun. It's like cooking or making music.

Danielle Brazell, she's the general manager for cultural affairs, she had a meeting with Francois Nion, a staff person with JCDecaux, they do all the bus stops. I told him what I was working on and he said, "Oh, I live in Mar Vista. You know what? We did a project in Chicago for one of the big perfume companies." You know those ads in the bus shelters? There was an ad for a perfume and in the middle of the glass was a chrome bucket and it said, Try Here. You stick your hand in the bucket and there's a light sensor and when your hands break it, it squirts a little bit of perfume on your hand. He said, "I can get that machine for you."

And so we retrofitted the perfume machine there. Each month for the next three months, we’ll change the perfumes.

The first scent is called Into Town. I got to do some research at the Huntington Library in Pasadena, they have an amazing archive there on California history and the arts. Back in the day, the cowboys would ride into town on their day off. Because they didn’t bathe they smelled pretty bad. There's a California sage brush, they would rub their bodies all around it and put their clothes on and ride into town. I took a couple pieces of the plant and went to the Institute for Art and Olfaction and said, "I want to make a perfume inspired by this plant."

The next one will be called Economic Development. That’s kind of a jasmine smell and then it starts to smell like vanilla coffee. And the third one is called Hollywood Springtime. That’s a reaction to having been born and raised in Hollywood. Hollywood always tells us there's four seasons but in Los Angeles, we don’t have four seasons. So this superficial concept of the four seasons has always been there. What I learned in the classes is that each perfume is like music, there’s a melody and the there's a midtone that helps move the melody through a choreography if you will and then there's a bass note and the bass note helps you remember the smell. I created Hollywood Springtime without any bass note so you could smell it and later on won't be able to remember it.

Was working with the city in a bureaucratic environment challenging?

What helped so much was that [the residency] didn’t come from staff, the public didn’t demand it. It came from the top down.

I tell my friends who are artists, "No one says no to me." I do have this background in government. I used to work for the LA Metro as a public arts administrator. So I do understand protocol and the ethics of public art. I also understand how much you can do something and where the line is. So I tend to want to push that line of course as an artist and I think that has served me well in the 12 months with LADOT.

What would you tell artists wanting to work with their city like you have? What can the arts offer city departments?

I think the challenge is, you always want to be true to your vision and your voice. That’s what we've been trained to do as an artist, to develop our voice. But having said that, when you're working in the public realm and inside a government department, the end product has to be beneficial to the public. I was trained to go out there and be able to talk to people who may or may not have any interest or experience in the arts and somehow help to create a win-win situation. But at the same time keeping voice.

With the perfume project, at LADOT, somebody said, "How can we get people to envision the street differently?" As I walked around downtown, I thought, there’s so many different smells…if we could change the smell of a street I wonder if that would change the perception of the street? I'm not sure if an architect or an engineer or a landscape architect would think about that. As an artist, that’s what you're trained to do. It's not better or worse, it's just different and that’s why they hired me.

I think the commonality between everyone at the table is communication. They're all trying to communicate. When I was first hired, they called me to one of these conference rooms and said "We’re working on this powerpoint for Vision Zero, would you look at it?" It was something like 26 pages, which right off the bat, that’s way too much information for anybody, much less the general population. And as they were showing it to me it was data-driven. After the fourth page of data, personally my brain shuts off.

I think it was page six or seven or eight, it talked about the relationship between pedestrian fatalities and car speed. I said, "Isn’t that kind of the main point? If we could slow down everything wouldn’t it save a lot of lives?" They said it was one of their top priorities. I said, "Well, why is that page eight?"

You also helped connect the department to the community a bit more, can you talk about how some of those relationships evolved?

So nobody evidently had ever contacted anybody in the Ghost Bike community and I thought that was kind of funny because in a sense they're working on the same thing. Often the Ghost Bike folks walk the ghost bikes to city property and then the city is the one that ends up cutting the lock and taking the bike away.

We just hit it off. There were a number of artists in the group and they understood what I was trying to do and what LADOT was trying to do and they educated me about the history of ghost bikes and what they were trying to do with all of these horrible bike fatalities, sort of an epidemic of sorts. Long story short, I became a member. That’s been very helpful, that relationship turned into the Vision Zero map. They actually pinpoint where these deaths occurred. There's a memorial element to it.

What's been the most surprising part of working with LADOT?

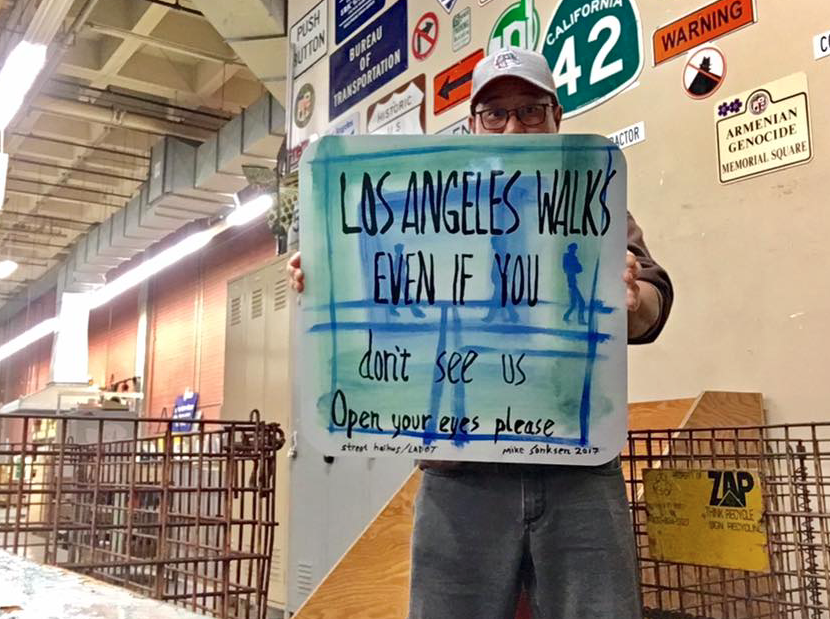

This was about midway through, maybe before, I had met this engineer, super nice guy who had been there for a very long time and I was trying to get the signage thing going.

I made a little watercolor of what my sign would like. I sent it to him. Well, that was my first mistake. There's no dimensions, nothing, it was just a simple watercolor. I said, "I want to do this on a street somewhere can you help me?" I'm in my truck driving home and he calls me, I put it on Bluetooth and started to talk and he said, "Alan, are you driving?" I said yeah and he said, "Well, that's very dangerous." I said I have Bluetooth and he said it didn’t matter. He said, "Anyway I got your drawing and I don’t get it."

Man I couldn’t sleep that night, I was so pissed off. I was thinking, these engineers, they don’t care. The next morning he emails me. It's not a new idea, he found it online and said, "Alan, is this what you were talking about?" And of course it was. But I said, before we go there, I have to tell you, I was very upset after our call, I really didn’t appreciate the way you were addressing me. And he just called me immediately and said, "I have to tell you what happened before we were on the phone. As one of the head engineers, every time there is a police report that has to do with traffic it pops up on my screen. Right before we talked that morning I got two deaths where a car was making a right turn, didn’t see the person who had the right of way about to walk off the curb and they got hit. Two incidents in the course of two hours. Those people were automatically killed. In both cases, Alan, the driver was on Bluetooth."

He's very passionate and he said, "This is going to happen. I'm going to help you. I don’t want you to be angry. This is our job and we’re not doing our job. Two people got killed, I shouldn’t be getting paid." That’s what he said. As he hung up, I thought, "Oh my God, Alan, you idiot. Last night you thought he didn’t care but in fact he cares the most."