The history of informed consent stretches back to ancient Greek times largely involving the relationship between doctors and patients, but within the age of technology, informed consent now includes personal data being used by large tech companies.

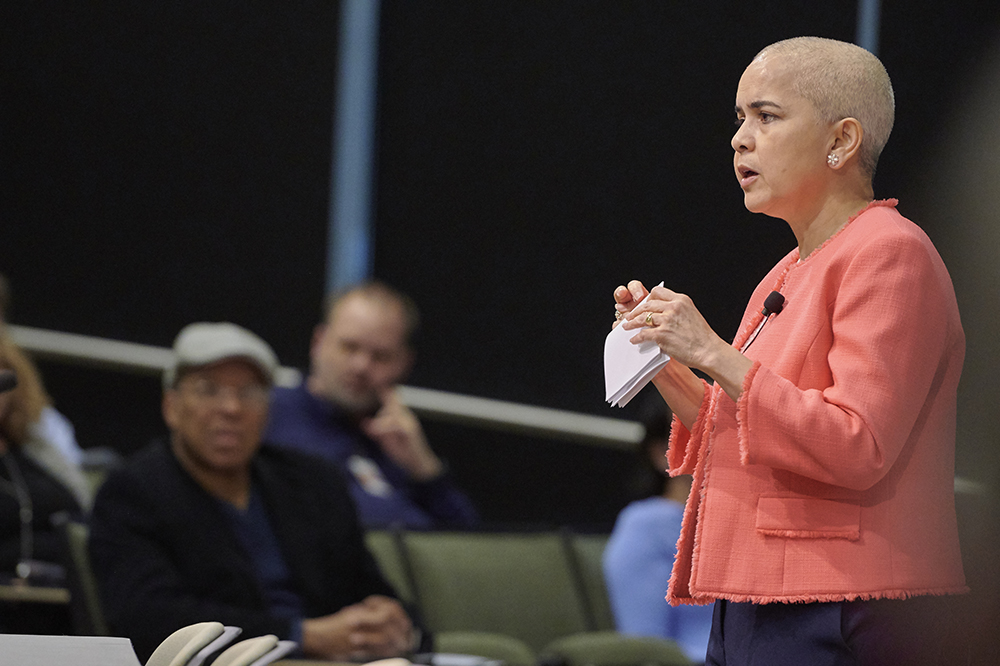

And according to former Rice University Provost Marie Lynn Miranda who spoke Monday during the first Symposium on Data Privacy, the reality of informed consent has changed into being neither informed nor consensual.

To start, Miranda pointed to the modern history of consent starting with the 1947 Nuremberg Code. She highlighted three of the ten principles including that the participant must be informed of the experiment and consent to it freely, the experiment must be performed by an experienced professional and the experiment must have the potential to yield fruitful results for the good of society. Miranda then pointed to the 1953 NIH Clinical Center Policy, which set the precedent that all ethical responsibility for medical experiments lies with the study's principal investigators. The provost also pointed to the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and the 1979 Belmont Report.

These examples are the foundation of informed consent, but Miranda argued that this foundation is no longer guiding companies' terms of services and privacy policy agreements.

"Now the argument is that with these long consent forms that are several pages long, users are no longer informed nor consensual, because these forms are too long," Miranda said during her presentation.

Twitter's privacy policy, she noted, is 9,000 words, Google's various platforms have a combined 10,000 words and Apple Music's is just under 20,000 words, which is actually longer than William Shakespeare's "Macbeth."

"If teens don't like reading 'Macbeth,' then they are definitely not reading these terms and conditions that are longer than the Shakespeare classic," Miranda said.

The question of whether people are actually reading various terms and conditions was the foundation of "The Biggest Lie on the Internet" study, which investigated the privacy policy and terms of service policy reading behavior of adults. Researchers Jonathan Obar of Michigan State University and Ann Oeldorf-Hirsch of the University of Connecticut estimated the privacy policy for a fictitious social media service called "NameDrop" should have taken anywhere from 29-32 minutes, based on an average reading speed for an adult at 250-280 words per minute. Furthermore, the terms of service should have taken about 15-17 minutes to read. Instead, the experiment found that the participants took an average of 73 seconds on the privacy policy and 51 seconds for the terms of service.

"Implications are revealed as 98% missed NameDrop terms of service ‘gotcha clauses’ about data sharing with the NSA and employers, and about providing a first-born child as payment for access," the report said.

Miranda continued saying the balance between data privacy and impactful research is a double-edged sword. "On the one hand, opportunities for research are enormous, but people don't really know what they're consenting to in the present and they certainly don't know what they're consenting to in the future," she said.

"When smartphones first came out, people were agog by the technology, but now we are all beginning to understand the implications of these technologies," Miranda said. "But we aren't going to give up our smartphones or our FitBits, but I can choose to use it the way that it is useful to me, instead of defaulting to the set settings."

During the symposium, other experts and educators from around the country spoke on data privacy. Keynote speaker Deborah Frincke, the director of research for the National Security Agency/Central Security Service, spoke on the difficulty of team members working together on projects with different levels of security clearance. "What's the downside of data privacy and security levels? You have a group of people that need to work together, but not everyone has the same information." The additional keynote speaker, Simson Garfinkel, the senior computer scientist for the U.S. Census Bureau, spoke on the security of the 2020 census moving online and what the bureau is focusing on to maintain the security of American's information and ensuring the information isn't altered by potential hackers.

Rachel Cummings, assistant professor of industrial and systems engineering and computer science at Georgia Tech, presented her findings regarding the incentives for companies to protect users' information saying in part, "To all of these high-tech companies that are making us concerned about our data, they will actually fare better if they protect our privacy."

Dan Wallach, professor of computer science and electrical and computer engineering at Rice University, highlighted his work in creating a more secure and trustworthy voting system but noted that his work hasn't been implemented due to cost concerns. Stanford University's John Duchi, assistant professor of statistics, presented the controversial notion of "everyone's data needs to be public so that there is no longer a value to your data being released." Naturally, not everyone was thrilled at his argument with some highlighting voting and health information potentially affecting their private and professional lives.