Social mobility, or intergenerational mobility, measures the economic mobility between generations and social strata in society. It is a way to conceptualize the “American Dream;” the idea of hope and determination will allow anyone to achieve their highest goals and aspirations in America.

The Harvard University’s Opportunity Insights’ Opportunity Atlas, an interactive map and research product based on data from 20 million Americans and their parents’ census and tax records, shows the neighborhoods in America that offer children the best chance to rise out of poverty. The research helps ground discussion of poverty and inequality in economic mobility and the role of place in a child’s development.

We can use the Opportunity Atlas as a tool in the short-term to understand the effect of current policy focused on economic mobility and place-based initiatives. Additionally, we can use the Opportunity Atlas as a stepping stone and invest in measuring and understanding the dynamics of social mobility and opportunity locally.

We cannot rely on the Opportunity Atlas as a long-term tool as there is a decay in the “predictive power of tract outcomes” roughly every decade, which is corroborated by other research.

How successful is the current policy?

In the Houston region and nationwide, alleviating opportunity disparities fall into two public policies:

- Moving people to opportunity: programs to move people from “low opportunity” areas to “high opportunity areas” through affordable housing programs.

- Placed-based investments: improve upward mobility in low-opportunity areas.

Moving to opportunity: housing choice vouchers

Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV) are an example of “moving to opportunity” policies, which are generally small in scale and hard to measure as a success. Realistically, we cannot move everyone from low-opportunity to high-opportunity neighborhoods. The populations with the most to gain from “moving to opportunity” programs are young couples with very young children.

According to the Houston Housing Authority’s Administrative Plan for Section 8 Housing programs, preference, up to a cap of applicant households, is given to the homeless, transition-age youth, families who are involuntarily displaced by government action, and under-housed families living in public housing.

The map below shows the Opportunity Atlas for household income outcomes for children of all races and genders with low-income parents. In the context of the Opportunity Atlas, the map shows the household incomes of the children of low-income parents, once the children hit age 30. Red denotes areas of low economic mobility, while the blue areas are areas of high economic mobility and opportunity for low-income parent households. The points represent the centroid of the corresponding census tracts with at least 150 Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) recipients reported.

Carlos Villegas

As the map shows, Harris County’s HCVs are concentrated in areas of low opportunity.

For “moving to opportunity” programs to work, affordable housing has to be located in areas for opportunity. With the vast majority of high-HCV neighborhoods located in areas of low opportunity, what is the point of affordable housing in an area of no opportunity? Indeed, in the last year, the City of Houston finally came to a resolution with HUD after being found to have violated part of the Civil Right Acts based on a development decision. Despite the resolution, there is still local contention on Houston’s policy.

“Moving to opportunity” programs are often the most contentious, locally and nationally. Not in my backyard (NIMBY) mentality is both real and perceived. However, if this program was reformed to help those with the most to gain—young low-income couples with infant children—how could NIMBYism challenge fledgling parents?

Place-based investments: Complete Communities Initiative

Neighborhoods with high opportunity have low poverty rates, more stable family structure, greater social capital and better school quality. A place-based approach is built on understanding the structure of communities.

In a chapter of The Dynamics of Opportunity in America, University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Tim Smeeding highlights the critical components of social mobility within a life-cycle model. Family formation is important to childhood development, with each stage of life building on the next; in the end, adulthood outcomes are built on the middle stages of life. Measuring and empirically understanding the importance of indicators in each stage is the foundation of the place-based approach.

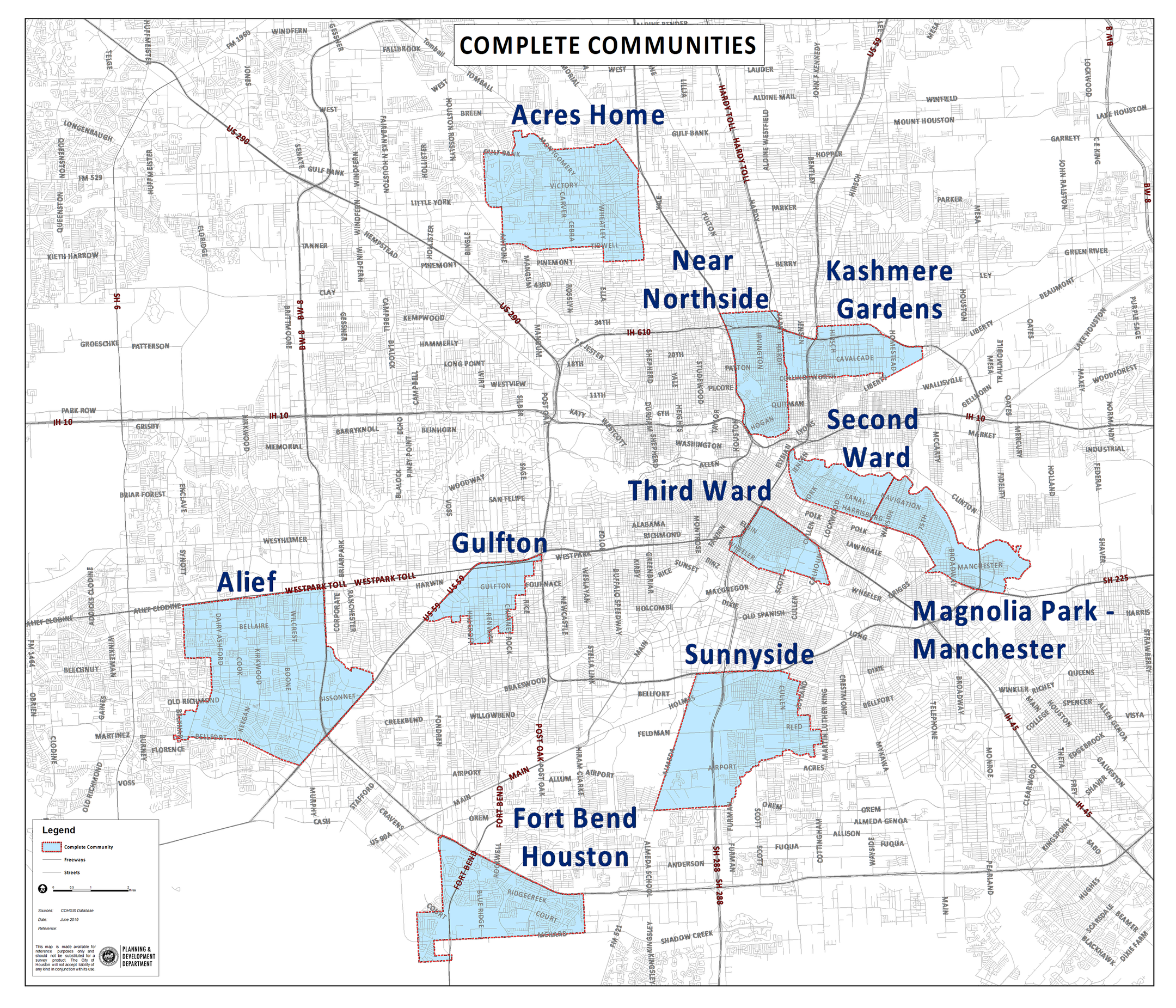

The Complete Communities initiative is an effort from the City of Houston to improve historically under-resourced neighborhoods. This place-based approach was undertaken in 2017 with five pilot communities and has recently been extended to five additional communities.

While Complete Communities is indeed aspirational, it is unclear how successful this initiative will be—place-based improvements are important but often take a generation before gains can be realized. The success of the initiative could also be challenged by the lack of dedicated funding and reliance on private funding. Further, the focus is not entirely on low-opportunity areas. Alief, a community highlighted in the Opportunity Atlas and one of the Complete Community neighborhoods, is an ideal location for affordable “moving to opportunity” approaches.

Moving forward with social mobility

The novel idea of the Opportunity Atlas is the use of big data. Medical and government records have huge potential to be leveraged for public policy improvement.

Our current “moving to opportunity” policy is not successful, at the very least it intends to help people out of poverty. We don’t know if our place-based policy will be successful without the systematic measurement of social mobility and life-cycle indicators.

Our regional success is imperative in the success of all neighborhoods; we will never know if we are succeeding with the waxing and waning of resources between communities. There is only one Houston region. We still eat, work, enjoy leisure and root for the same sports teams together.

If we care about social mobility, the region needs to improve HCV programs to move people into opportunity and measure social mobility and life-cycle indicators, beyond simply reporting the descriptive statistic. Big data, informed through the place-based indicators, will tell us what is working. This cannot and should not be done by government alone. Philanthropy, private industry, academia, and the government have stakes in moving forward with social mobility.