Last summer, Kinder Institute researchers estimated that evictions cost Harris County upwards of $240 million annually (pre-pandemic figures). We revisited the model using post-shutdown eviction data (since March 15, 2020) and estimate that during the pandemic, evictions have cost Harris County-area jurisdictions and nonprofits upwards of $100 million. These critical funds, which could go to improving the area’s public health response, transportation, public safety, housing and education sectors, instead have been used to address a problem that was more successfully prevented in other Texas cities.

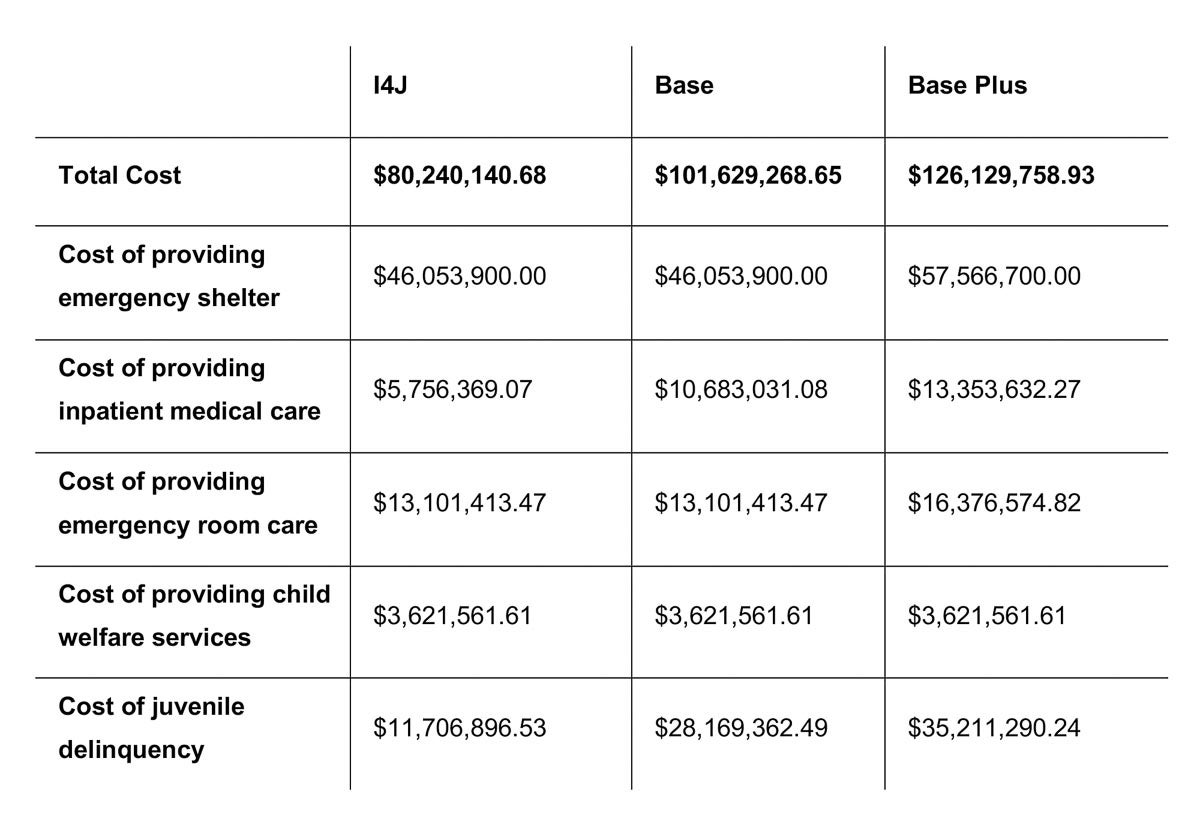

The $100 million estimate is based on the “Cost of Eviction Calculator” created by the Innovation for Justice Program (“i4J”) at the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law. Our cost estimate considers the costs of emergency shelters, child welfare, inpatient medical services, emergency room visits and juvenile delinquency. Cost assumptions in the estimate are supported by empirical research. There are likely other areas fiscally impacted by evictions that are not reflected in our estimates because the cost per eviction is unknown. Most importantly, these costs represent a significant burden to an already strained patchwork of entities working around the clock to respond to the extensive social, psychological and economic trauma wrought by the pandemic.

Methodology: The i4J Eviction Cost Calculator can be found here, while a more detailed explanation can be found here. Other studies that have used the calculator can be found here. The calculator asks a series of questions, which are estimations for various relevant statistics on shelter usage, health care demand, criminal justice costs and evictions.

In this memo, we detail our estimates, assumptions and calculations. We also enumerate each broad statistical category, our own estimate and its source. We attempted in all cases to acquire local numbers, which was not always possible. In these cases, we used cost estimates from other major cities.

Eviction disparities

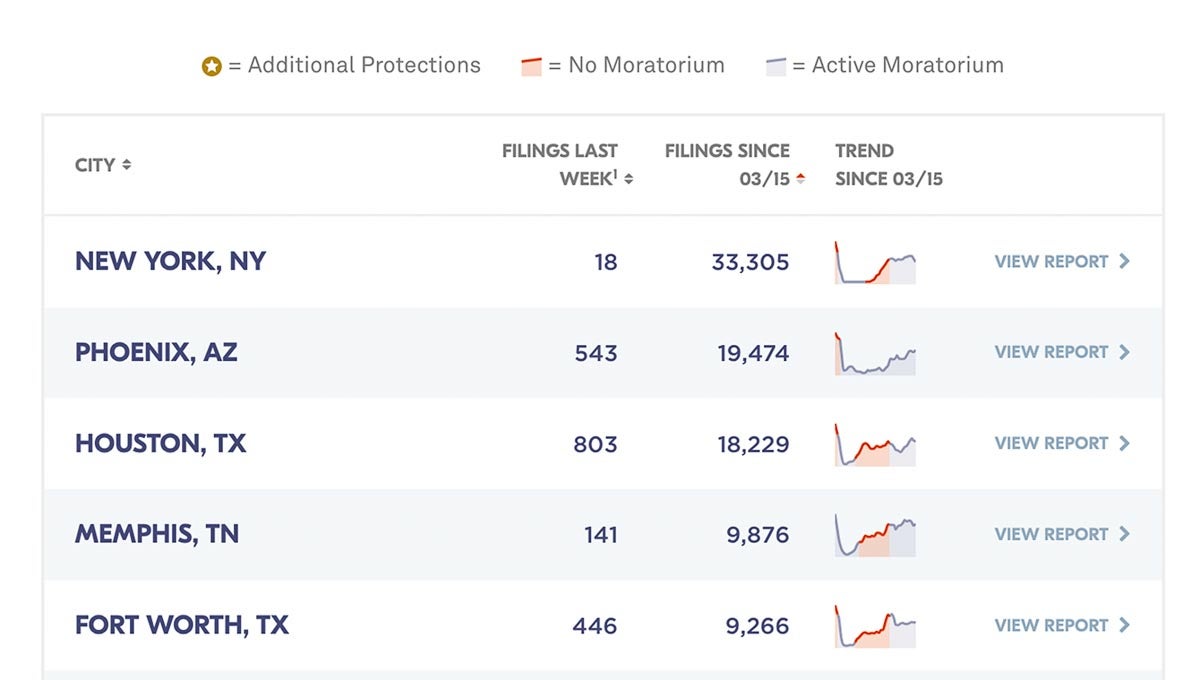

Recent eviction trends reflected in Princeton University’s Eviction Lab dashboard drew our attention after seeing Houston listed as the city with the nation’s third-most eviction filings since March 15, 2020, when the pandemic shutdowns and subsequent recession began. Between then and Dec. 12, 2020, 17,057 households in Harris County were evicted (Eviction Lab also includes 1,172 evictions filed in Galveston County in devising its ranking, but only Harris County filings were included in this assessment). Five counties of the New York City area had the highest total while Maricopa County in Arizona, where Phoenix is located, was just ahead of Houston at No. 2.

This is not a big surprise as Harris County was second only to New York City in evictions before COVID-19, but the magnitude of evictions since the shutdowns compared to Travis County (i.e. Austin), a region operating in a similar regulatory environment, is quite remarkable. For instance, pandemic-era evictions in Travis County totaled 725 since March — just 4% of Harris County’s 17,057 evictions, even though its population is one-third the size of Harris County’s.

In addition to more downstream costs, evidence is emerging that more evictions equal more COVID-19 cases and deaths. A recent study found that 150,000 cases and 4,500 deaths could have been prevented in Texas if the state had kept its moratorium on eviction proceedings in place instead of letting it expire back in late May.

Inadequate federal response

This also comes on the heels of the latest COVID-19 economic relief package, a deal that noticeably left off direct support to state and local governments that are dually impacted by depleted tax revenues and the need for an agile pandemic response. By law, state and local governments are not able to run fiscal deficits on operating budgets and therefore are resorting to austerity measures, which include laying off very much needed front-line workers. The new federal stimulus also extends the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s eviction moratorium through the end of January 2021; however, an analysis by the local data science firm January Advisors found that the federal government’s eviction moratorium has helped in less than 10% of all local eviction filings — a sobering reality check.

Local response can make a difference

Federal support is therefore only a part of the picture and local government intervention can make a difference to the housing stability of vulnerable residents. The eviction discrepancy between Travis County (725) and Harris County (17,057) can mainly be attributed to the proactive intervention of Austin’s city council, which opted to institute its own version of an eviction moratorium through February 2021. The council also added additional tenant protections, including a 60-day grace period for tenants who fall behind on payments through March 2021, that have been extended four times since the shutdown.

Undoubtedly, Austin’s measures have kept thousands of vulnerable households sheltered during the pandemic — a noteworthy example for officials in Houston who refused to add their own eviction grace period, despite support from a broad coalition of tenant advocates, developers and community development organizations. Instead, the City of Houston and Harris County have offered rent relief on two different occasions through CARES Act funding, though the funds have been hard to reach for some tenants because landlords have to self-register to unlock eligibility for their tenants. And despite rent relief funds, evictions continue to be filed, serving as a vivid example of the serious need for more direct housing aid.

Above all, the high cost of evictions represents a moral hazard to local jurisdictions, as the cost of evictions is spread across various entities and rent relief efforts are paid for by the CARES Act (house money), yet the devastating effects of homelessness are disproportionately borne by our most vulnerable residents. Paired with the fiscal impact estimates, Austin’s case illustrates that an equitable housing response and fiscal responsibility are not mutually exclusive approaches in responding to the current housing crisis and can be a template for other local governments in Texas to emulate.