Two weeks ago, we at the Kinder Institute released a report on the financial difficulties of Texas’s three largest cities and we confidently stated that, in the coming economic downturn, police departments would be spared budget cuts while all other cities services (except perhaps fire departments) would be the first on the chopping block.

Two weeks feels like a lifetime ago. Our report was released three days after the tragic death of George Floyd, killed by a Minneapolis police officer, but before the resulting protests had crested — and long before mounting public discussions about dismantling or defunding police departments. It soon became clear that public confidence in police departments and their budgets would quickly erode.

Today, the question of how to protect the public — and how much money to give to police departments — has been turned upside down.

It wasn’t very long ago that the prevailing view in most public policy circles was that the best way to deal with deficiencies in policing was to throw more money at police departments. When the Dallas City Council adopted its 2019-2020 budget last September, the Dallas Morning News published an editorial headlined: DALLAS BUDGET GIVES POLICE A MANDATE AND RESOURCES TO MAKE THIS A SAFER CITY (though the editorial made the point that, given more resources, the police department now had to step up and address well-known internal problems.)

As recently as five weeks ago, the Morning News published another editorial headlined: THE NEXT DALLAS BUDGET WILL HAVE TO PROTECT PUBLIC SAFETY SPENDING WHILE OTHER SERVICES ARE CUT BACK.

But last Wednesday’s Morning News headline about the police department read: MOST DALLAS COUNCIL MEMBERS CONSIDER DEFUNDING THE POLICE AND USING THE MONEY FOR OTHER SERVICES.

And while “defund the police” has become a rallying cry among protestors, it has also occasioned a new look at the many social functions that have fallen to police departments in the past 20 years as well as the increasing militarization of police equipment.

In recent years, police departments have simultaneously taken on more social responsibilities and acquired more paramilitary equipment. “The police have been used to fill the gaps where city services are not adequate,” Charles H. Ramsey, the former police chief in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., told The New York Times on Friday.

Most large Texas cities, including San Antonio and Austin, have also faced pressure to “defund” the police in some way. In Austin, the City Council decided to reduce the police budget by $20 million. The money will be diverted from vacant sworn-officer positions to other functions, such as social services and criminal justice diversion programs. That’s a reduction of almost 5% in the police department’s budget, which totals almost $450 million. And it came toward the end of the fiscal year, as Austin — like San Antonio and Dallas — runs on an October 1 fiscal year.

The response in Houston, characteristically, was more muted. Last week, the City Council approved a budget for fiscal year 2020-21 (Houston runs on July 1 fiscal year) that actually increased the nearly $1 billion police budget by 2% — from $945 million to $964 million.

At-large Council member Letitia Plummer had proposed a $12 million cut not unlike the one Austin passed, that would divert money from long-vacant positions to other purposes, including beefing up the Independent Police Oversight Board. However, the City Council rejected her proposals. Like many of his counterparts across the country, Mayor Sylvester Turner did tighten up police practices on the use of force.

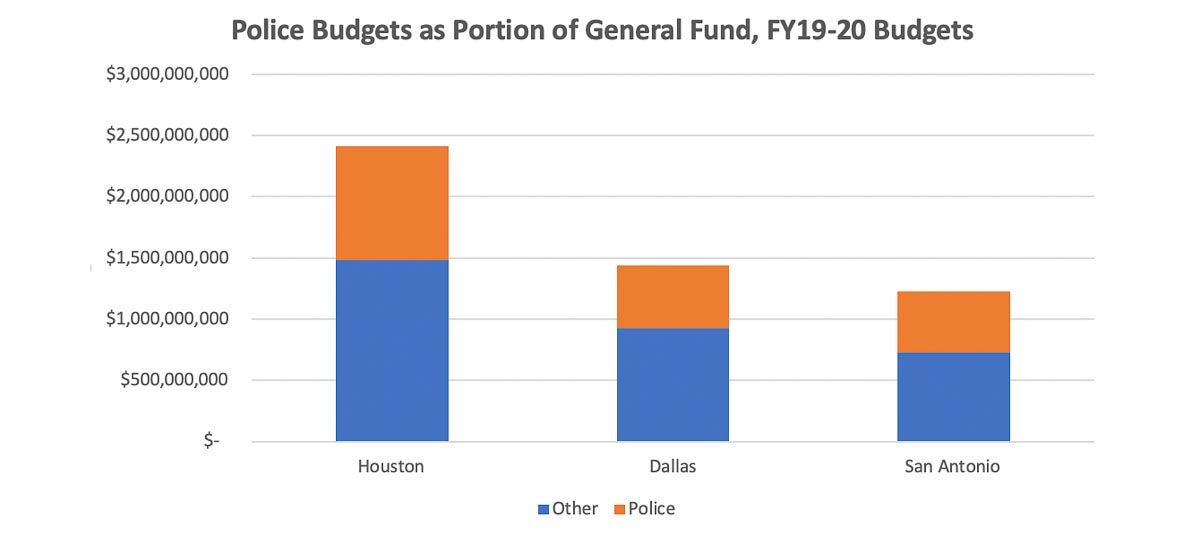

Police departments typically receive more “general fund” revenue than any other municipal service. A recent report by the Kinder Institute comparing the finances of the three largest cities in Texas — Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio — found that together the cities spend about $2 billion a year on police service. In all three cities, this figure represented somewhere close to 40% of the general fund budget.

One possible change that has been discussed in both Dallas and Houston is to eliminate the police department for the school district and folding the school police into the regular police department. As Kinder’s 2018 report on overlapping services in law enforcement found, 25 school districts in Harris County have separate police forces — a highly unusual circumstance, nationally. Houston Independent School District spends almost $20 million per year to retain a force of well over 200 sworn officers.

It remains to be seen whether the police budgets in large Texas cities will be substantially reduced, even in this time of troubled municipal budgets. But one thing is for sure: The role of police departments in our communities will forever be altered, as more and more people question whether the police should take on such a wide range of roles out on our streets.