As the head of the Department of Education considers rolling back guidance regarding disciplinary practices for student populations that have been overrepresented in suspensions, expulsions and referrals to law enforcement, newly released federal data for the 2015-2016 school year reveal that not only have disparities persisted but they've actually increased for black students and students with disabilities when it comes to interactions with the police.

“We know from many other studies that there are no discernible differences in the way that black students behave in school” compared to their peers, Kaitlin Banner, an attorney with the Advancement Project, told the Washington Post. “The disparities come from the way that adults in the school building are responding to the student behavior.”

District- and campus-level data reveal similar disparities in the Houston Independent School District, the largest in Texas. Overall, though black students made up just 24 percent of the district's enrollment, they represented 37 percent of the students receiving in-school suspensions, 51 percent of those receiving out-of-school suspensions and 56 percent of expulsions as well as 53 percent of the referrals to law enforcement, according to data from the 2015-2016 school year released by the Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights.

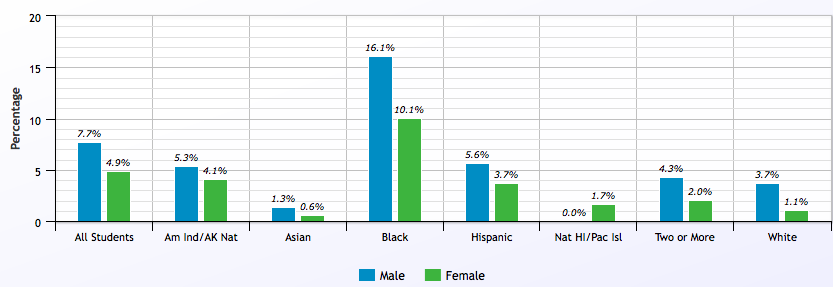

Black male students without disabilities were more than four times as likely as their white male peers to receive an out-of-school suspension, while black female students without disabilites were 10 times as likely as white female counterparts to receive an out-of-school suspension. Hispanic students were also more likely than their white peers to receive an out-of-school suspension.

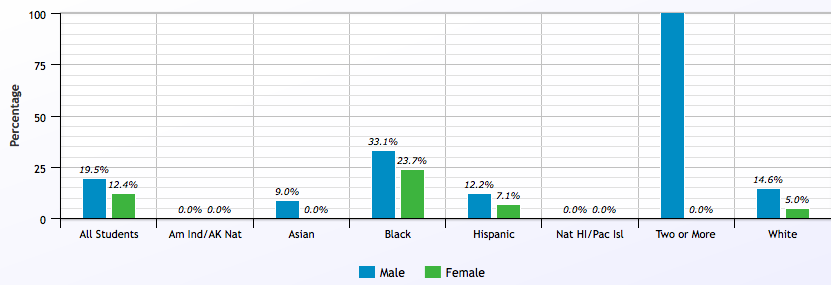

The disparities were there but less pronounced for students with disabilities, for whom the likelihood of receiving an out-of-school suspension was much higher overall than for their peers without a disability.

Within the district, research from the Kinder Institute's Houston Education Research Consortium has also shown that a student's disciplinary history is a signficant predictor of their likelihood to drop out of school.

Students Without Disabilities Receiving Out-of-School Suspensions by Race, Ethnicity and Sex. Source: Office for Civil Rights.

Students With Disabilities Receiving Out-of-School Suspensions by Race, Ethnicity and Sex. Source: Office for Civil Rights.

A deeper dive into the school district's 36 comprehensive or magnet high schools shows wide variations by campus with some consistencies. The analysis did not include charter schools and alternative campuses. Since the year the data was collected, several campuses have changed their names, including Reagan High School which is now Heights High School and Lee High School which is now known as Wisdom High School. The names used in the charts below reflect those used in the 2015-2016 school year.

Across the 36 campuses included in the analysis, black students were the most likely racial or ethnic student group to be underrepresented in a school's gifted and talented program and overrepresented among in-school and out-of-school suspensions.

Of the district's comprehensive and magnet high schools, there were only two schools where black students were overrepresented in the gifted and talented program versus 30 where blacks students were underrepresented relative to the school's student body population, according to an analysis of the data.

When it came to discipline, however, black students were overrepresented. In roughly 85 percent of the schools that had reported some in-school suspensions, black students were overrepresented relative to their share of campus enrollment. They were underrepresented in only four of those schools.

Similar patterns held for out-of-school suspensions. Black students were overrepresented in roughly 86 percent of schools that reported issuing out-of-school suspensions and underrepresented in only four of those schools.

In 10 of the 36 schools, more than 10 percent of black students were considered chronically absent, including 47 percent at Worthing High School and 44 percent at Yates High School.

The picture was a bit more mixed for Hispanic students, the plurality of students in the district. When it came to gifted and talented programs, for example, they were overrepresented in roughly 64 percent of the schools analyzed relative to their share of enrollment but in eight schools the difference was three percentage points or less. They were underrepresented in just nine of the schools.

They were overrepresented in in-school suspensions in just nine of the 33 schools that reported issuing in-school suspensions. That number went down when looking at out-of-school suspensions, where Hispanic students were overrepresented among those receiving punishment in just four of the 35 schools that reported issuing out-of-school suspensions.

Ten percent or more of the Hispanic students at 20 of the 36 high school campuses were considered chronically absent, according to the data.

Asian and white students were also more likely to be overrepresented in gifted and talented programs and underrepresented in disciplinary actions. White students were overrepresented in the gifted and talented program at 18 of the 36 high schools and underrepresented at just seven of those high schools, but not by a significant amount at any of those campuses. Asian students, meanwhile, were overrepresented at eight high schools and underrepresented by marginal amounts at just nine of those campuses.

Turning to in-school suspensions, white students were underrepresented at roughly half, 16 out of 33, of the schools that reported issuing in-school suspensions and overrepresented at just four of those schools by small margins. Asian students were likewise more likely to be underrepresented than not, which happened at 19 of the 33 schools for in-school suspensions and 20 of the 35 schools for out-of-school suspensions. White students, meanwhile were underrepresented at 15 of the 35 schools for out-of-school suspensions and overrepresented at just 10 of those campuses.

The campuses also had wide variations in terms of the total number of suspensions issued, an important variable when considering disparities. So even though the Energy Institute High School had the largest overrepresentation of black students among those receiving in-school suspensions, the school of 561 students only reported two in-school suspensions overall. Compare that to Yates High School, for example, a school of 927 students that reported 459 in-school suspensions. Had those been evenly distributed across the student body, about half of the students there would have received an in-school suspension. There, black students were only slightly overrepresented among those receiving in-school suspensions, but they still accounted for 90 percent of the student body and 95 percent of the in-school suspensions.