Christof Spieler is known for a lot of things. Nationally, his 2015 bus route reimagining as a board member for Houston's Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County has earned praise and interest from other cities looking to do something similar. Here in Houston, he's the vice president and director of planning at Huitt-Zollars as well as a senior lecturer with Rice University. But he's also known for another relatively unique thing: he actually rides transit.

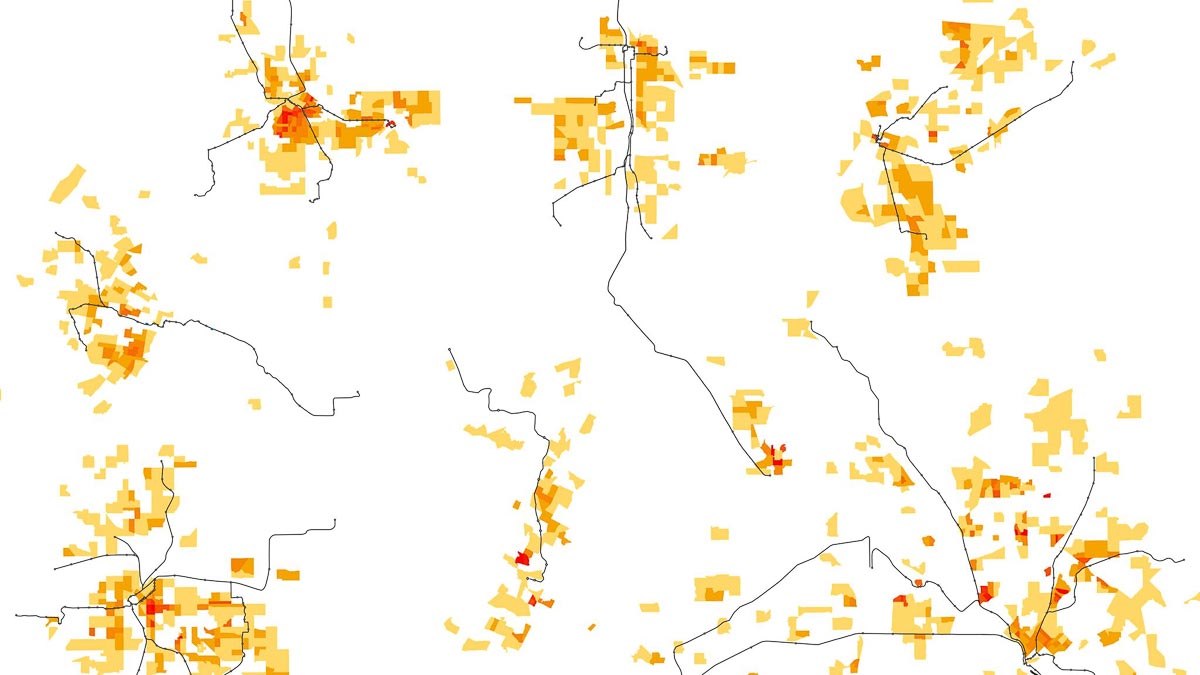

After surveying 47 cities with light rail or bus rapid transit systems for his new book "Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of US Transit," Spieler said he saw lots of missed opportunities and missteps when it comes to transit planning. The book even includes lists like "Most Useless Rail-Transit Lines," which includes Nashville's Music City Star, Jacksonville's Skyway and Cleveland's Waterfront Line. And the book's beautiful maps that plot transit networks against density show just how often lines miss the major population centers they should be connecting.

There a number of takeaways from the book, including the key elements of a good transit system. Things like density (build where people are and want to go, particularly when locating stations), connectivity (rail should connect to bus), reliability (take traffic delays out of the equation by giving transit its own dedicated space), frequency (which Spieler said was the "most important thing to really making transit useful"), legibility and walkability are among the critical components of a city's approach to transit planning. "All of these things are fairly obvious if you ride transit," said Spieler at the Kinder Institute's Urban Reads discussion of his new book Wednesday.

But there's the problem, or at least a big part of it. The failures he identifies in many major transit systems are due, in part, to the lack of voices who actually ride transit.

It's an old problem, as Eric Jaffe noted in CityLab back in 2014:

The problem is familiar to transit leadership across the country. In August, a San Francisco Examiner op-ed challenged the people who run Muni to "actually ride Muni." Last year, an analysis of Chicago's CTA found that the board chair rode the system only 18 times in 2012, and a Washington Post survey found many D.C. Metro board members either couldn't or wouldn't "name the exact bus lines or rail stops they used regularly." In 2008, the vice chair of New York's MTA board famously asked: "Why should I ride and inconvenience myself when I can ride in a car?"

"If you're in New York City and you're driving," said Spieler Wednesday evening, "you should not be on the transit board."

The lack of transit rider voices in planning is also tied to another problem common to many transit systems in the U.S.: racial inequities and bifurcated systems and levels of service that treat so-called "choice riders" and "transit-dependent riders" differently.

"Race is under almost every transit issue in the United States," Spieler said, citing things like governance issues, debates around the distributions of transportation funding, resistance to effective regional coordination and more.

The roots of this, argued Spieler, extend back to the '60s and '70s when transit planning as we know it more or less took shape. At a time when the promise of highways to move people efficiently and without delay seemed to be failing and when bus systems across the country were likewise failing financially, transit agencies responded to both, but as distinct challenges. On the one hand, there were "choice riders," commuter types switching from cars to transit and the other hand, there were "transit-dependent riders" who often made do with inadequate service.

That stratification remains today in many transit systems. "That to me is the biggest equity issue in U.S. transit," said Spieler. "A lot of our decision making has actually had baked-in inequity," he said, noting that many transit decisions tend to reflect the interests of white, male, higher-wage populations, from big to small choices. Just think of stroller policies on local buses, for example, or how racism has fundamentally shaped the Atlanta metropolitan area's transit system.

And all of this ultimately means less successful transit systems for everyone. "I bet you, if I handed you a population and centers map, any one of you could design a transit system better than like half the transit systems in the United States," Spieler told the crowd. Instead of a false dichotomy of rail versus bus service, for example, cities should be paying attention to fights that matter, tackling local opposition to build broad public support for transit so that it can actually connect meaningful destinations. "If nobody is against your rail project," he said, "it's a bad project."

With that in mind, Spieler touched briefly on the current long-range plan in the works for Houston's transit system. No longer a board member, Spieler said he's evaluated the proposed plans at a high level and applauded them for avoiding seemingly attractive but ultimately pretty useless projects like a southwest rail line along U.S. Highway 90A. But he said there's room for more ambitious plans still.

"Transit should have a level of ambition to it," he added.

"Across the United States, we have a lot of opportunity to use transit to make people's lives better, but we have to actually put it in the right place," Spieler argued. "By bringing people together in cities, we create basically everything humanity is about...and transit does that incredibly well."