"When did Montrose become gay?"

Brian Riedel, assistant director of Rice University's Center for the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality, says he gets that question regularly. Almost as regularly, he hears people declare that the historic Houston neighborhood is no longer gay.

"I'm always interested in why histories become voiced in the present day," said Riedel, recognizing that different groups have different interests in both remembering Montrose's gay history and declaring the place today a more mainstream neighborhood.

In the 1980s, the historic neighborhood had a significant LGBT population, and for many years, the area was at the center for gay culture in Houston. Today, however, there's a sense among some Houstonians that this is no longer the case.

For real estate folks, the narrative of Montrose being formerly gay -- but not anymore -- could help them add a bit of historical character and a trendy narrative to the area, while still sanitizing the present image of the neighborhood, which sometimes was at odds with gay bars in the area, Riedel said.

It could be part of a story of victory -- claiming the history with pride, while also arguing that Houston's inclusiveness means a specific gay neighborhood is no longer necessary.

Or it could be a sort of lament about a changing understanding of what gay politics and organizing look like.

Within Houston's narrative of diversity, individual stories can sometimes become blurry. When Houston's Gay Pride Parade moved downtown from Montrose in 2015, some took it as a victory.

"The time has come for the Houston LGBT community to come out of the closet," said Frankie Quijano, president of Pride Houston, at the time. "The original purpose of Pride in the 1960s was to break down barriers and show that as an LGBT community we refused to be ignored. There is no longer a need for a segregated community in Houston."

Intrigued by not only the questions he received but the implications behind them, Riedel decided to look through the historical record to see what people really meant when they called Montrose a gay neighborhood and how the landscape has changed.

Riedel looked to old city directories, travel guides and copies of the short-lived Albatross (the first regular publication from and for Houston's gay community, published by a local bar owner) to document the city's gay bars and institutions, the spaces that helped birth a host of political groups over the years. He included long-recognized staples in the scene, including the restaurant Art Wren's, as well as the less explicitly gay hangouts, like the House of Pies on Kirby that many in the community called House of Guys.

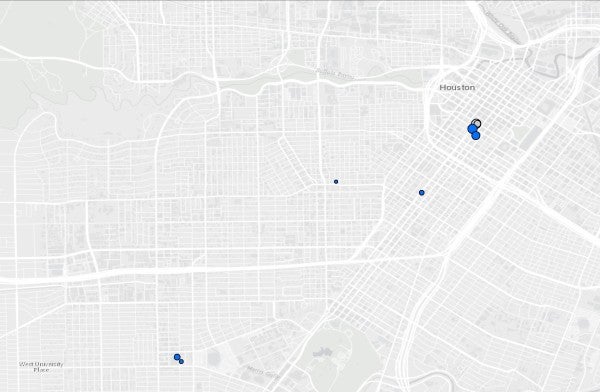

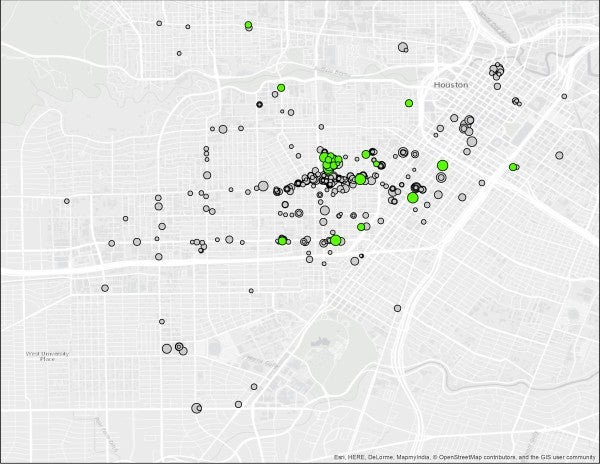

What he found was that in the early 1940s and 1950s, there was little indication that Montrose would come to play the role in gay Houston culture that it eventually did. Bars that were either explicitly or implicitly recognized as being gay-friendly dotted downtown before moving on to other areas like Rice Village. A couple years stand out to Riedel, who plotted when the bars opened (blue) and closed (gray), and which were still around in 2015 (green).

In 1969, when an early morning police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City, sparked protests and riots and served as a galvanizing moment for gay and lesbian communities across the country, Houston's gay bars, cinemas and other spaces were still scattered. Rice Village, downtown and Montrose all were part of Houston's LGBT scene.

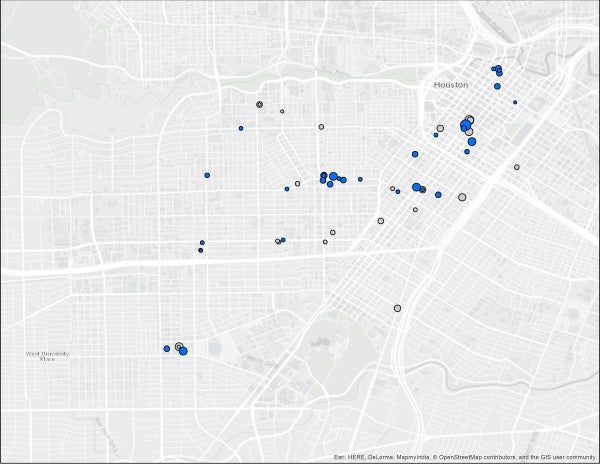

By the 1970s, said Riedel, businesses catering to an LGBT clientele shift to Montrose. And in the 1980s, as new wards opened and filled within days to treat AIDS patients, the intersection of Westheimer and Montrose becomes a clear center for social and civic life of many in the gay community. "We owe many of Houston's AIDS service organizations to conversations that happened at Mary's," said Riedel about the legendary leather bar on Westheimer where patrons "mourned and celebrated the lives of those lost to the virus," scattering or burying their ashes in the back of the property, Riedel wrote for OffCite. Today, the land where Mary's stood is now home to Blacksmith, a coffee shop.

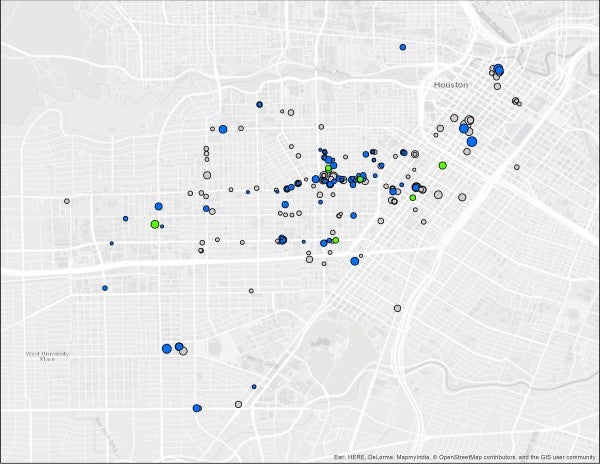

The 1990s were a kind of "heyday" for Montrose's gay culture, according to Riedel. In 2008, there were some 40 active locations catering to LGBT clientele in his records. By 2015, Riedel said, the number had declined, but he said people looking for the heart of the gay community in Houston would still head to Montrose.

There were significant milestones along the way: the boycott of singer and gay rights opponent Anita Bryant, who was invited to sing at the Texas State Bar Association meeting in Houston in 1977; the "Oddwads and Queers for Tinsley" t-shirts that helped rally support for Eleanor Tinsley for city council after a comment from her opponent criticizing her supporters, including the Gay Political Caucus; the various political groups that formed and the election of Annise Parker in 2009. As mayor, she was the first openly gay or lesbian mayor of a major city. She had already won citywide office multiple times before that election, breaking barriers along the way.

But there have been setbacks and uneven progress. LGBT, and particularly transgender individuals, still face elevated threats of violence. With a controversial bill working its way through the state legislature that would require transgender individuals to use the public bathroom that aligns with their birth gender and the recent defeat of the local Houston Equal Rights Ordinance that would've covered a whole host of groups from discrimination locally, including by race, age, sexual orientation and gender identity, hurdles remain.

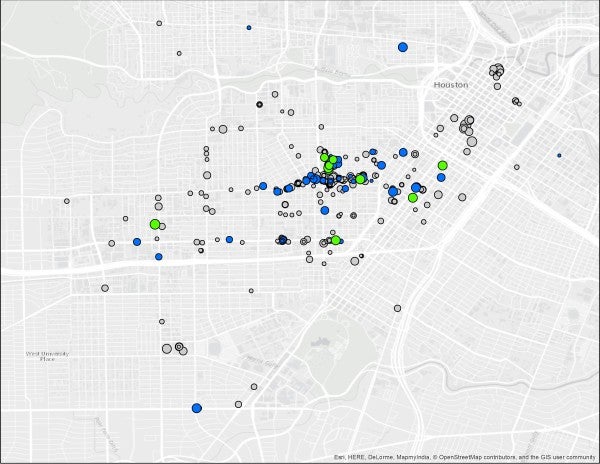

Riedel's research is still in progress and will be supplemented by dozens of oral histories, but he said his maps show not only loss, but simultaneous perseverance too, adding, "There is still a need to recognize and create a space for difference."

"If we mean the place where community institutions like bars are located, Montrose clearly is still the epicenter, though the maps do indicate there are fewer bars there now than before," he said. And he added, "many community organizations and nonprofits are still based there or still focus their social occasions in the area, if only out of habit."

But he added, "If we mean anything more expansive than bars, then the question is more debatable: for example, can the average LGBT person (who ever that might be) still afford to live in Montrose, whether as renter or owner?"

In one sense, he said, the maps "confirm that Montrose is no longer the same kind of LG(BT) neighborhood it was." But, Riedel added, "that says nothing for what relationships it will or must have to queer communities in the future."