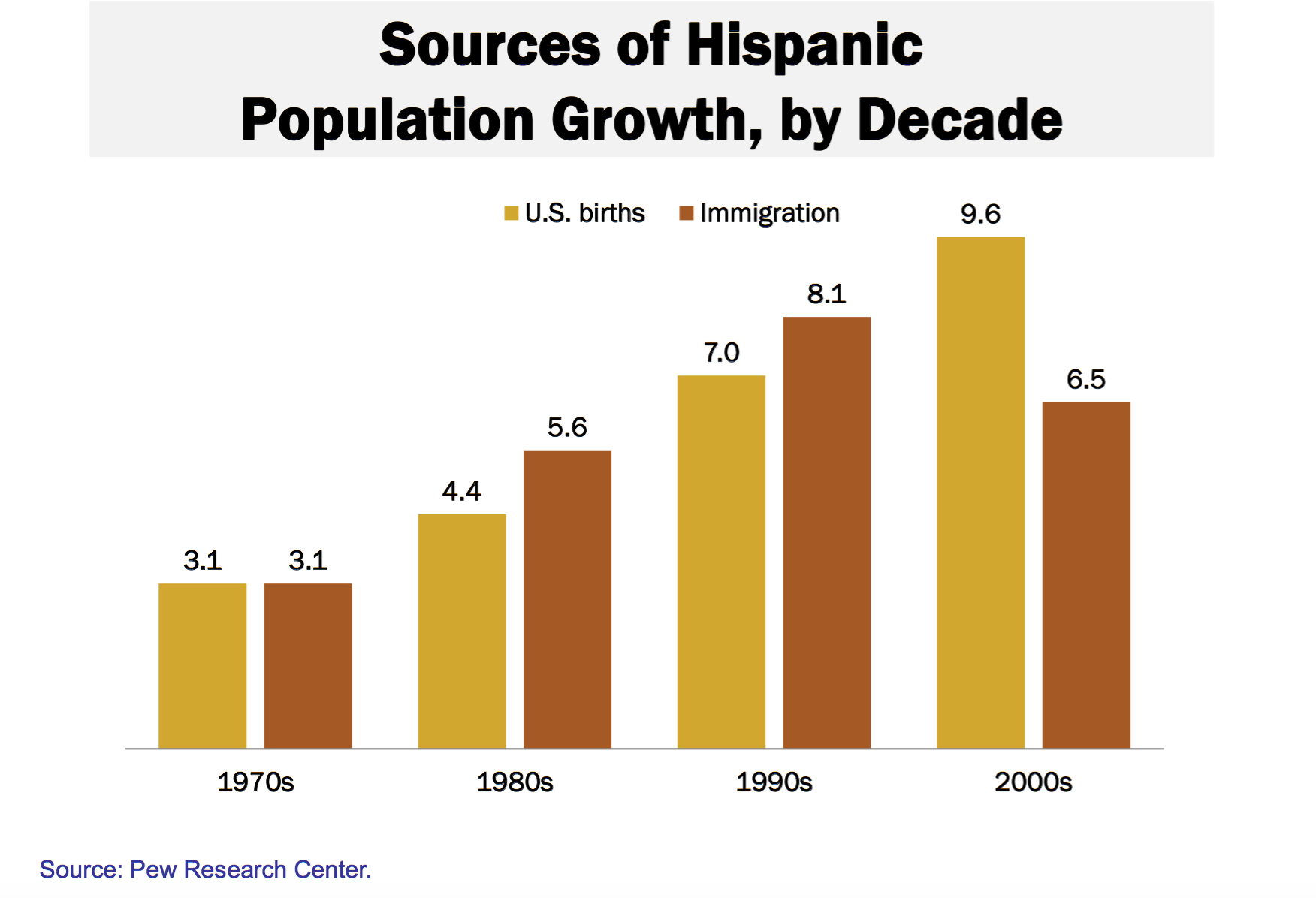

Nationally, a shift is underway in the Hispanic community. The population's growth was once driven by immigration but is now propelled through births here in the United States.

Today, Asian immigrants have replaced Hispanic immigrants as the fastest growing population of new arrivals to the country. And though the Hispanic community is still rapidly growing, experts in recent years have adjusted their projections of just how much growth to anticipate in the future. Once expected to make up 30 percent of the population by 2050, the Hispanic population is now projected to reach around 25 percent of the population by 2065.

Nationally, the shift seems to signal several important changes, according to Mark Lopez, Director of Hispanic Research at the Pew Research Center. With more growth from births rather than immigration, that means the overall Hispanic population is transforming. The use of the Spanish language in the U.S., for example, "seems to be coming to a peak," he said as more Hispanic Americans report using English at home. "The up and coming generation is more English-speaking than we've ever seen," said Lopez.

In the Houston area, the Hispanic population represents 36 percent of the metropolitan area today. And though the Hispanic community's evolution differs from the national narrative now unfolding, it still provides something of an example of some of the challenges that persist. Article continues below graph.

Houston's Hispanic population is a little different than the national community in significant ways. For one, Hispanic immigration to Houston is still greater than Asian immigration, despite a slowdown. The recession hurt Hispanic immigration, Lopez said, and thus the pace of Hispanic population growth. Growing at an average annual rate of 4.4 percent in the years before the recession, the Hispanic population's growth slowed to just 2.8 percent annually between 2007 and 2014, according to the Pew Research Center.

A large driver of the slowdown in Hispanic immigration both locally and nationally was the shift in Mexican immigration. Between 2009 and 2014, for example, the United States saw a net loss of some 140,000 Mexican immigrants leaving the country. "If there are no jobs," Lopez said, "people aren't going to come."

Still a greater portion of Houston's Hispanic community is foreign-born than the Hispanic population nationwide (39 percent versus 35 percent). But this number is decreasing locally too. And the metropolitan area has a lower rate of naturalization among eligible immigrants across its immigrant populations than the national average -- 45 percent versus 60 percent.

But Houston mirrors some national trends as well.

Nationally, the Hispanic population is skewing younger. So while half of all Hispanic people born in the United States are under the age of 19, according to Lopez, more than half (53 percent) of all Hispanic people born in the United States in Houston are under the age of 18, according to census data.

"It's really a story of young people, which means education, issues of entering the workforce," explained Lopez.

In Houston, an increasing share of the Hispanic community has some sort of higher education, growing from 26 percent of the adult population to 33 percent in 2015, according to estimates from the American Community Survey.

At the same time, however, Hispanic youth are more likely to be both not in school and not working, according to Kinder Institute research. And the percentage of the Hispanic population living in poverty increased from 22 percent in 2010 to 24 percent in 2015, well above the overall Houston area poverty rate of 15 percent.

Indeed, progress in Houston has not been linear. "U.S-born Latinos have advanced much farther than first-generation immigrants in general, but progress stalls after this point," concluded a 2014 Kinder Institute report on Houston's Hispanic community. "The third and later generations of Hispanics are not obtaining substantially more education or making more money in better jobs than the second generation."

In polling, Hispanic Houstonians are the most likely to agree that "If you work hard in this city, eventually you will succeed," but the limited inter-generational gains suggest there are other barriers influencing that success. Cuban immigrants, for example, tend to come to Houston with higher levels of education than those from Central America. And then there are barriers they face once they arrive, including schools where the local non-profit Children At Risk estimated almost half of the students were at risk of dropping out and that struggle to ensure all students finish school ready for college.