According to one recent study from MIT, one-third of the American workforce has switched from working in offices to working at home in the past two months. And a recent poll from Gallup found that most workers don’t want to go back.

Let’s say they don’t go back — at least not full-time. There’s no question that the trend toward remote work among office employees will profoundly change metropolitan areas — both cities and suburbs.

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

For close to 30 years now, millions of people have crawled to work every day from residential suburbs to large job centers through rush-hour traffic jams, even though they mostly sit in front of a computer screen and move information around all day long. They’ve been forced to do so because jobs, in the parlance of economists, are geographically “sticky.” That is, companies don’t move jobs around very often.

When downtowns went downhill starting in the 1960s, a lot of jobs did move from cities to suburbs — the so-called “Edge Cities” (in Houston, think the Galleria area or the Energy Corridor.) But since then, they haven’t moved much, which is why people endure horrific commutes like the one from Riverside County to Orange County in Southern California — a 30-plus mile drive along a single congested freeway, State Route 91.

Have the sticky jobs become unstuck?

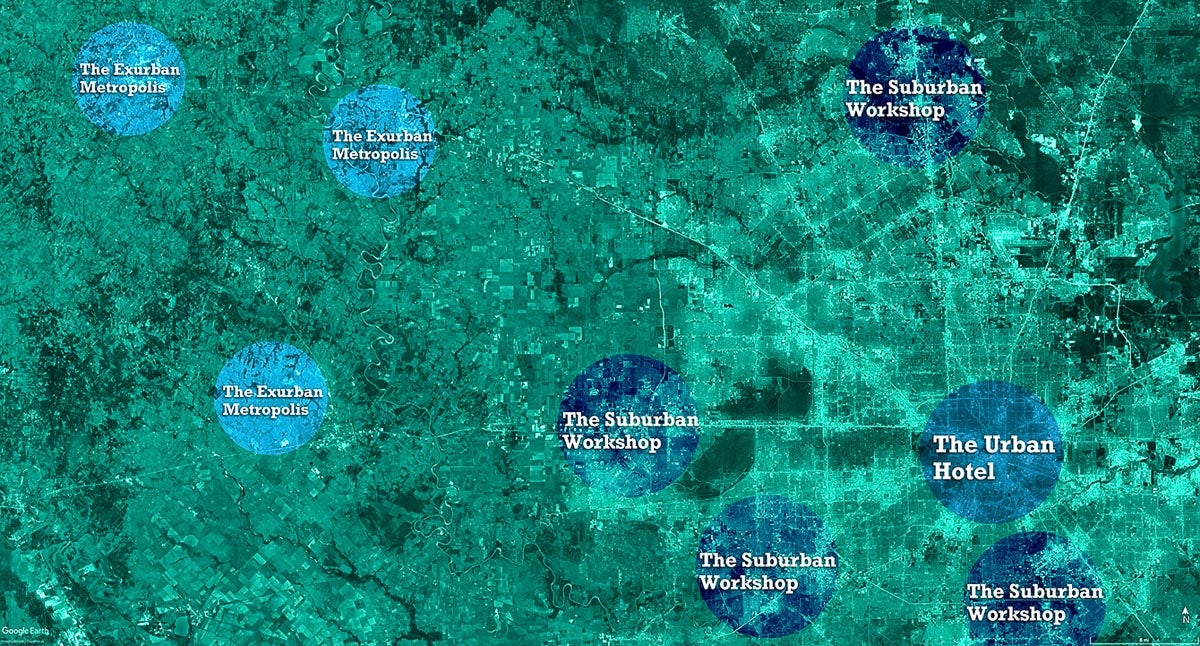

But the trend toward remote work might finally dislodge the sticky jobs from the big job centers to distant residential suburbs. And that’ll accelerate two trends that have been ramping up: the transition of downtowns and other job centers to what might be called the Urban Hotel, and the transition of residential suburbs to what might be called the Suburban Workshop. In the process, both of these types of places will change and accommodate a more diverse set of activities. In other words, they’ll become more interesting places to be.

Meanwhile, the big unknown is whether part-time remote work will lead to what the cantankerous urban critic Joel Kotkin calls an “age of dispersion.”

Will the ability to work remotely encourage people to sprawl even farther into exurban locations, far from the city? Will it even encourage them to move to smaller cities and rural locations around the country? Just how “un-sticky” will jobs become, and how will that affect overall settlement patterns? Kotkin’s probably at least partly correct that a growing Exurban Metropolis is coming, but how widespread that trend will be is hard to predict.

It’s important to note that this applies to only part of the workforce — office workers who sit in front of screens and move information around. A huge portion of the workforce will remain — in the middle of the COVID-19 crisis still is — tied to a daily commute because they do work that must be done in a particular location. Unless they’re highly paid — and most of them aren’t — they’re likely to live in less desirable, amenity-poor locations, trapped in their cars on long commutes and almost completely separated from both the Urban Hotel and the Suburban Workshop. And that’ll further separate office workers and other workers into two classes — one that’s able to take advantage of local freedom and one that is not.

The Urban Hotel and the relevance of location

A half-century ago — in the Mad Men days — a dense office district like Midtown Manhattan had to accommodate all workers simply because computers had not yet come into common use. Office work had already been separated from manufacturing production — corporate headquarters in Manhattan were far away from their factories — but the office workers had to all be in one place. Everybody had to be near their paper; their paper had to move efficiently from one location to another; and the only way to keep a close eye on your employees was to watch them and their flow of paper closely.

All of that began to change three decades ago, at the dawn of the Internet age, when information began to move electronically rather than physically. At first, many futurists thought this would lead to a dramatic flight of what we now call knowledge workers from urban centers. In 1989, the Los Angeles Times reported on a variety of business professionals who were using computers and modems to work from Lake Tahoe, Santa Barbara and other exotic and remote locales. “Telecommunications,” one business professor told the Times, “really makes location not so relevant.”

And, indeed, it wasn’t long before an enormous amount of office-based work was taking place remotely — but from Bangalore, not Lake Tahoe. And it wasn’t the high-paid work moving to distant locations because of the Internet. Instead, it was the routine work, which moved around the globe seeking the cheapest labor.

By contrast, high-paid knowledge workers, especially the millennial entrepreneurs, clustered in coffee shops and shared workspaces in Brooklyn, San Francisco, Santa Monica — dense, expensive urban neighborhoods located in a few trendy cities, mostly on the East and West Coasts.

We’ll always need to meet face to face

Even the tech geniuses who have made it possible to work on mountaintops don’t work on mountaintops. The tech industry has built itself into a global economic powerhouse on the idea that connecting remotely — by video, phone, email, instant messaging, Facebook, Snapchat, whatever — is an adequate substitute for being there in person. Yet the companies themselves are concentrated in Silicon Valley, where the tech workers interact in person all the time, move from job to job and company to company.

In other words, what we have seen is a shift from the urban workshop to the urban hotel. By this, I don’t mean that downtowns and other dense job centers will literally consist of nothing but hotels (though hotels play an important role in this transition). What I mean is that — even more than in the past — these locations will exist primarily to facilitate face-to-face contact that simply cannot be replicated in any other way. There’s so much that happens in an in-person meeting that Zoom can’t provide: body language cues get picked up, human connections are made, trust gets built.

The Urban Hotel provides the infrastructure for face-to-face meetings. Hotel meeting rooms, restaurants, coffee shops, food halls, convention centers, conference rooms in office buildings and co-working spaces — all of these provide the venues for face-to-face contact. And, of course, face-to-face contact isn’t possible — or at least it’s inconvenient — if people aren’t already located in close proximity to one another, either by officing in the area or staying in one of the hotels.

The Suburban Workshop: More room without the commute

At the same time that job centers transition to the Urban Hotel, plain-vanilla suburbs will transition to the Suburban Workshop — a trend that will be accelerated by office employees working at home full or part time.

The original idea of the suburb was to create separation between the city — in the 19th century, the dirty, smelly, polluted city — and the pastoral setting believed to be required for a healthy family life. Suburbs were an upper-class luxury until after World War II, when the mass production of housing and federal financing of mortgages made single-family suburban life possible for most people — at least for most white people.

Today, most Americans live in the suburbs. And for most families, locational decisions about suburban life revolve around the geometry of commuting.

How far away from work do I have to live to afford the house I want?

How much time am I willing to devote to driving every day?

How much separation from my home life am I willing to tolerate?

And for families with two (or more wage-earners), it’s not just geometry but triangulation: How do we optimize our daily activity pattern when it involves driving to work (often in different directions) and shuttling kids around?

The ability to work at home even part time blows all those calculations to pieces. All of a sudden, you don’t have to go anywhere very far from home, at least on some days. You’re returning to the life of your great-great-grandparents in the 19th century, when most work of all kinds was done at home. You have turned your house into a Suburban Workshop, where most of the work of a company — work that does not require face-to-face contact — actually takes place.

The trend toward the Suburban Workshop has been with us for some time, as more and more people find ways to work for small businesses near their house, rather than large companies in big job centers. But there’s been an upper limit to the growth in the Suburban Workshop simply because jobs are “sticky” and most employers have required their workers to be in the office, even if they spend most of their day sitting at their desk, looking at a computer screen and doing work they could do from anywhere.

But just as the trend toward remote work will transform the Urban Hotel, it will transform the Suburban Workshop as well — in at least three ways.

When suburbanites work in big job centers, they have a variety of options for going out after work near their office. When they work at home — or at their local co-working center — they’re not likely to be content with their local Applebee’s.

The suburbs will look more like the city

First, not everybody will want to — or be able to — work at home, even if they can. Some will prefer to go to an office, though they may not want to commute a long distance. But the crash-and-burn of the retail business might provide an opportunity here: Empty retail spaces in your local strip mall could be converted into co-working spaces for people who can work remotely but don’t want to work at home, especially if an employer offers an allowance for working remotely. (And many might do so, especially if it’s cheaper than the cost to rent office space employees use only occasionally.) So, the strip mall may become part of the Suburban Workshop.

Second, more people will demand more amenities closer to home. Households without children at home — and that’s most households, even in the suburbs — go out to bars, restaurants and other events more often.

When suburbanites work in big job centers, they have a variety of options for going out after work near their office. When they work at home — or at their local co-working center — they’re not likely to be content with their local Applebee’s.

Once again, the cratering of bricks-and-mortar retail creates an opportunity: Once the COVID-19 crisis shakes out, look for new and innovative local bars and restaurants to pop up in vacant retail spaces. Maybe even food halls in the suburbs.

And finally, the millennials will show up in the suburbs.

A big question over the past few years is whether millennials will leave the city for the suburbs once they start getting married and having children. It’s a question that urbanists fear the answer to and urban critics gloat over.

And the answer is: Of course they’ll move to the suburbs.

In large part, they have no choice — there are far more residences located in suburbs than in cities in America. And in part, millennials will go to the suburbs for the same reasons that previous generations have gone: schools, space and a little peace and quiet.

But they’re going to bring their urban sensibility with them. They’re going to want places and spaces that are charming and walkable and have a lot of amenities — places where they can reconstruct city life to the greatest extent possible. Think Sugar Land Town Square or The Woodlands Town Center. These are the kind of suburbs that will be most in demand — and that developers will fall all over themselves to create. Like the Urban Hotel, the Suburban Workshop will be a more interesting place to live.

The Exurban Metropolis: Working remotely — literally

If you don’t have to commute to work every day, won’t you live farther away? After all, if the possibility of remote work breaks the geometry of commuting and the triangulation of activities in a two-earner family, that opens up a lot of possibilities about where you can live.

Some evidence suggests that people who commute only occasionally, rather than every day, often choose to live much farther from city centers. For example, many firefighters — who often work a couple of 24-hour shifts each week — choose to locate their families 60 to 90 miles away from where they work. So, there’s no question that some people will make this choice in order to get a bigger house on a bigger lot.

But not everyone will make that choice. Sometimes people are surprisingly “sticky” even if jobs are not. They grow up in a particular neighborhood or live there for a long time. They establish networks — family, friends, church, businesses — that they are reluctant to leave behind. And, as I mentioned above, the millennial generation values proximity to amenities far more than their parents and grandparents. They may move to the suburbs but that doesn’t mean they want to drive 6 miles to the store or 20 miles to church or spend all weekend on their John Deere.

Working from home 100% of the time is unlikely

A more profound question is whether the rise of remote work will cause people to flee expensive metropolitan areas altogether because they are completely untethered from a job location.

This is an argument that Joel Kotkin has made extensively, relying on — among other things — recent survey data that suggests half of the millennials in the Bay Area would leave if they could. And all you have to do is look at the growth rate and housing prices in Sacramento — a reasonably urbane city 80 miles inland from San Francisco — to see that there’s some validity to this argument.

But I think a widespread “age of dispersion” is unlikely for several reasons.

First, most remote work probably won’t be full time. If you still have to go to the office once or twice a week, you might move 50 miles away, but you’re not likely to move 500 miles away.

Second, the fact of the matter is that most people don’t move very far during their lifetime.

The majority of us end up living close to where we grew up, for the same reasons we might not move to the exurbs — family, friends, church, neighborhood. If anything, these factors have become more powerful over time. Internal migration within the United States has dropped dramatically since the 1980s, across all groups and all geographies.

Third — and this is a real wild card — it’s impossible to know if white-collar work will even stay in the U.S. once it’s not connected to a job center. If you can work remotely full time, will you be able to take your job with you to some distant location in the U.S.? Or, as economists have predicted for years, will your employer decide that even skilled white-collar jobs should be farmed out to cheaper locations like India?

And finally, even if people flee dense, expensive cities like New York and San Francisco, that doesn’t mean they’re going to flee urban life altogether. They’re likely to go to smaller, less expensive cities like Pittsburgh — a popular destination, according to one New York Times account, because it’s not as expensive as Brooklyn.

But Pittsburgh, hilly though it might be, isn’t exactly a remote mountaintop. Though cheaper than Brooklyn, it has experienced a similar post-industrial gentrification, driven in large part by the engineering and tech geniuses at Carnegie Mellon University, which is located in Squirrel Hill, a long-established Pittsburgh neighborhood.

So, in the post-pandemic world, escaping New York doesn’t necessarily mean leaving proximity and urbanity behind. It may simply mean finding an Urban Hotel — or maybe a Suburban Workshop — somewhere else.