Houstonians living in the most diverse large metropolitan area in the country know that behind those numbers are plenty of segregated neighborhoods. It's a recurring theme in research about this region and many others across the country.

Now, a new study examining the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the U.S. finds that much of that segregation is thanks, in part, to white families seeking out white neighborhoods -- and specifically, predominantly white schools. So even as residential segregation has been declining in recent decades, the new report from the University of Southern California found that those declines were smaller for children with families.

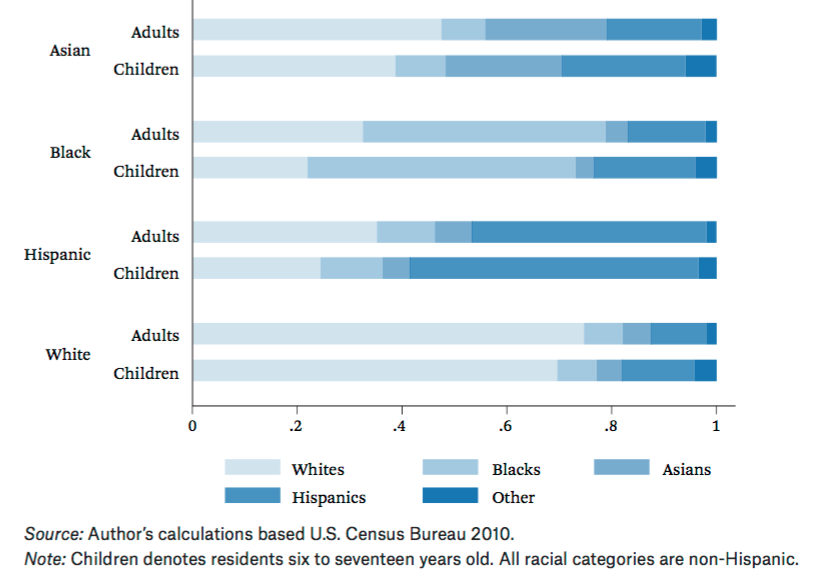

"This means that children are surrounded by greater racial homogeneity in their neighborhoods than adults," said Ann Owens, an assistant professor at the university and author of the study, in a statement.

Comparing data from the 2000 and 2010 Census in the 100 largest metros, Owens measured segregation in a number of ways, including looking at both adults' and children's exposure to other racial and ethnic groups as well as how evenly each census tract matched the overall demographic profile of the region.

By looking at families with children, Owens hoped to better understand the link between schools and segregation. She noted that even with the rise of school choice policies -- which let parents enroll their kids in schools they aren't zoned to -- the majority of public school students still attend their neighborhood school anyway.

White families, in particular, seemed to drive the segregation according to Owens' analysis. Those families -- often more economically advantaged and thus more able to locate in expensive areas -- also factor in racial composition of neighborhoods and schools in deciding where to live, according to prior research.

Locally, here in Houston, Kinder Institute research has also reached similar conclusions. Among economically advantaged parents living in affluent neighborhoods in the Houston Independent District "poor minority students have come to represent a sort of collective code for failing, low-quality schools as well as impoverished and dangerous neighborhoods," determined a 2015 study by the Kinder Institute's Houston Education Research Consortium.

Parents asked to discuss how they chose the best school option revealed an understanding of quality that was "most often shaped by larger cultural understandings of race and class, rather than by school academic quality indicators."

Not only does that trend drive segregation within a district -- think the highly competitive magnet programs that enroll disproportionately high levels of white and Asian students in HISD -- but it also contributes to segregation between districts, which actually accounts for more segregation overall, according to Owens. Article continues below map.

Map by Leah Binkovitz

Source: American Community Survey 2014 5-Year Estimates, Texas Education Agency 2014 District Snapshots

"White parents may be avoiding school districts where black and Latino children live because they use racial composition as a proxy for quality of a school and a neighborhood," Owens said in a release about the report.

Kinder Institute research bears out that idea locally too. Twenty percent of white survey respondents in Harris County said they probably wouldn't move into a new house if the neighborhood was 60 percent black, even if it was their dream house close to work, crime rates were low and the schools were high-quality, according to data from the 2016 Kinder Houston Area Survey. And the bias tended to be more against black people than Hispanic people: only 8 percent of white respondents said the same thing about a neighborhood that was 60 percent Hispanic.

And even though black, Hispanic and Asian parents may also factor school composition into their decisions about where to live, notes Owens in the report, their options are likely more limited than those of whites families. Black and Latino families have lower incomes on average than white families, and they face housing market discrimination that influences where they live, regardless of the high value that they may place on school options, Owens said.

In the largest metropolitan areas, Owens found, the average black child lives in a neighborhood where the majority of the other kids are black. Hispanic children and white children also tended to live in a neighborhoods where most of the kids shared their same background. And across the board, children were in neighborhoods with more segregated populations when measuring exposure to their own age group than adults.

Unsurprisingly, as the Hispanic population grows largely due to new births, all groups of children were more exposed to Hispanic children between 2000 and 2010.

Building on a growing body of research tying neighborhoods to a wide range of disparities, the report noted, "Higher segregation among children than adults suggests that more minority children than minority adults are exposed to neighborhoods of concentrated disadvantage." Because school selection is one of the factors driving segregation, the report argued, policymakers need to understand how neighborhood segregation is connected to school segregation.

"The two contexts are intertwined, and a policy that breaks the link between school attendance and neighborhood residence -- beyond intra-district school choice plans -- is necessary to break the cyclical relationship and reduce inequality among both contexts."