Image via missingmiddlehousing.com

Image via missingmiddlehousing.comDesigner Karen Parolek has noticed a similar trend in neighborhoods across the country.

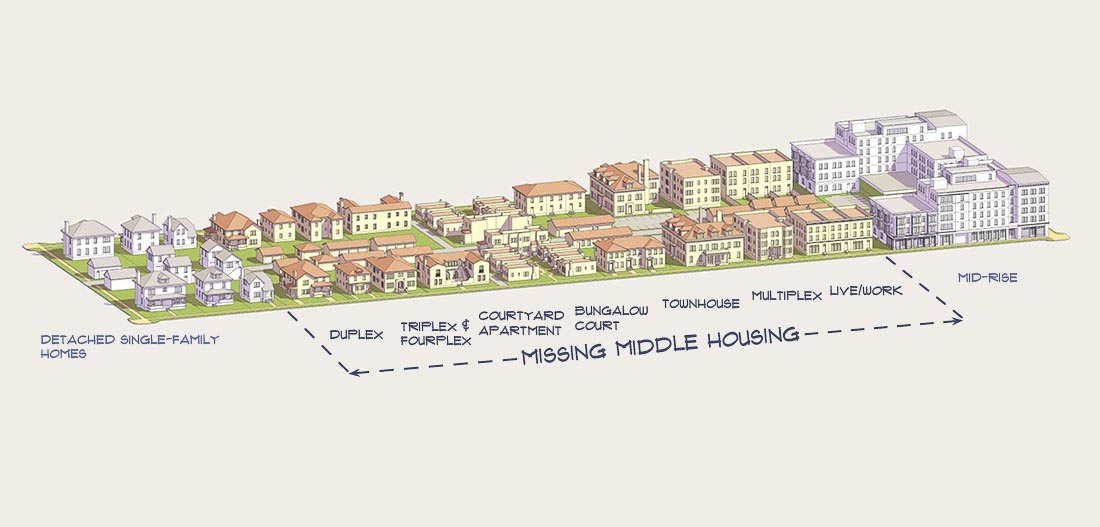

In just about every city, the communities that locals love tend to have a mix of housing types. Sure, there are single-family homes, but among them are duplexes, small multiplexes, and courtyard apartments, too.

The mix makes for a place that’s vibrant and walkable -- but not imposing, either, due to a lack of dense mid- and high-rise apartments. She and her partner at her Bay Area consulting firm coined a name for that mix: the "missing middle."

"In every city we’ve looked at, there are examples of this," Parolek said. "Density is scary to people. But this isn’t scary."

The problem Parolek, said, is in many (if not most) places, that type of housing is illegal. It just doesn’t jibe with the zoning codes. Now Parolek, a consultant who helps cities rewrite their zoning codes, is on a mission to help cities embrace the style.

Parolek and her colleagues took note of the missing middle in the midst of the recession, when large-scale development had stalled. As she saw it, the difficult period offered an opportunity to open the doors to smaller types of projects that might have a chance to thrive when larger projects had stalled. At the same time, she reasoned, those areas could probably contribute to the walkability of communities by making them more dense.

The idea was based on her travels across the country: many cities' most walkable neighborhoods are zoned for single-family homes, she noticed, and even looked like they mostly contained single-family homes. But upon a closer examination, they contained things like duplexes and fourplexes. They didn’t look that different from houses, but they contained more units.

She realized that, for many reasons, this type of housing might offer a key opportunity: within cities, it’s often more affordable than single-family homes, and it helps to create the kind of density that supports transit in places where high-rise apartments wouldn’t be appropriate.

The housing can take a variety of forms, from duplexes to fourplexes, to small courtyard apartments, and even some small multiplexes. The key is that it looks appropriate, even in areas with single-family homes.

Article continues below images.

Image via Opticos Design

Image via Opticos Design Image via Opticos Design

Image via Opticos Design Image via Opticos Design

Image via Opticos Design

Generally, the most dense missing middle housing isn't much larger than an 8- or 12-unit building.

Done right, a missing middle unit shouldn’t look all that different from a single family home either. Ideally, the only giveaway would be the number of mailboxes out front. "This is really a way of telling people density doesn’t have to be scary, if it’s done right," Parolek said.

Importantly, the housing can serve a variety of functions. In some cases, it can be distributed throughout a neighborhood, right alongside single-family homes. In others, it can be placed at the end of a block filled with single-family homes. And still other times, it can fill a void as a valuable transition between single-family homes and big apartment units.

Article continues below diagram.

Image via Opticos Design

Image via Opticos DesignInterestingly, the housing style isn’t new. It's often found in pre-1940s neighborhoods where it often played a critical role in so-called streetcar suburbs. But Parolek argues that the disappearance of missing middle housing over the years has made cities less walkable. She argues that cities should tweak their zoning laws to preserve the style in older areas while working to expand it into newer areas.

One of the biggest hurdles to that effort is that it's a style many developers are not familiar with. It’s often a difficult sell to investors and financiers -- who are more likely to pursue traditional, larger apartment building that they know how to build and finance -- on something that seems unusual. But she believes market trends are on her side, as a growing number of people are willing to trade the space that comes with larger suburban homes for the amenities that come with city living.

She cites data from land use strategist Christopher B. Leinberger that there's a 20 to 35 percent gap between the supply and demand for walkable, urban homes. Building missing middle housing might allow some developers to maximize their return in areas where high-density housing wouldn't be feasible. "We realize that (financing) is part of the challenge," Parolek says, "but I think more and more people get the demographic shift."