Landmarks are, as researchers Conner Bruns and Brent Chamberlain argue, "universal features of human urbanization." They are part of the urban fabric and, often, part of the mental maps people moving through the city generate and rely on as they navigate. The connection between landmarks and wayfinding has been well established but better understanding exactly how these cognitive maps come about, as well as their potential consequences, may be useful in planning more socially cohesive cities.

In their recent study published in the Landscape and Urban Planning journal, Bruns and Chamberlain showed one of the ways new technologies are being applied to the study of cognitive mapping.

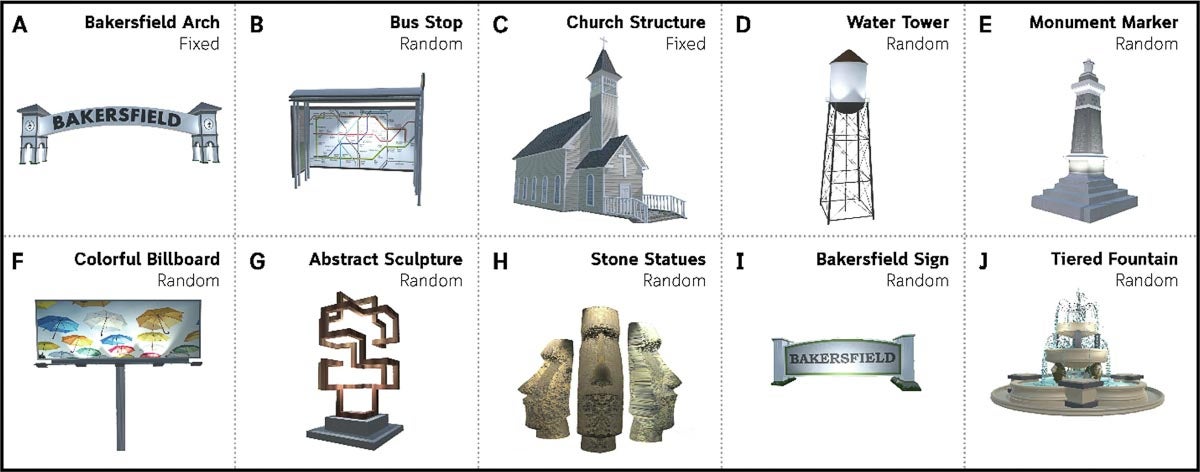

The researchers used virtual reality technology to confirm the critical role landmarks play in creating an accurate "spatial memory." Sporting headsets, participants were led through a virtual environment marked by a handful of different landmarks. The researchers then asked the individuals to retrace the route from memory on a sheet of grid paper and to locate the landmarks along the route. The researchers were able to do things like randomize the appearance of the landmarks to see whether a certain type of landmark was more memorable or effective in orienting participants.

"The empirical study and unique testing instrument substantiate that the spatial configuration of landmarks is valuable to navigation and wayfinding," the study concluded. "This provides evidence for landscape and urban planners to holistically consider spatial layouts of landmarks (not just landmark design) within urban design frameworks."

Source: Landscape and Urban Planning.

The authors argue that urban planners should take a proactive approach to landmarks, creating a Landmark Configuration Plan "to guide the design, configuration, implementation and preservation of landmarks."

In practice, doing so would likely mean contending with the often complicated social contexts of landmarks and of wayfinding in general.

Recognized as establishing much of the theoretical framework used to investigate cognitive mapping today, Kevin Lynch wrote in Image of the City in 1960 that, "Nothing is experienced by itself, but always in relation to its surroundings, the sequences of events leading up to it, the memory of past experiences." That idea holds true not just for the physical environment but for our social environment as well.

Indeed, some scholars have pushed back against the use of virtual technology for its lack of social context. "[W]ayfinding in many—perhaps most—real-world cases has a critical social dimension to it," was how a recent journal article put it. "These experimental environments are typically devoid of other 'people,' although they do not need to be."

In thinking about crime and criminalization, sociologist Wenona Rymond-Richmond argued that invisible elements of the city also contribute to cognitive maps, particularly for marginalized communities. "Cognitive maps are a response to abandonment and discrimination by police and other formal mechanisms of social control, and they inform and restrict residents' daily travels by warning them of safe and dangerous physical and symbolic spaces," wrote Rymond-Richmond in an essay in The Many Colors of Crime.

Given the social complexity of cognitive maps, landmarks must be understood as part of a layered wayfinding experience. In his interviews with residents of three different cities back in the mid-20th century, Lynch found that residents of the expansive, multinodal Los Angeles struggled to conceptualize the city.

"When asked to describe or symbolize the city as a whole," he wrote, "the subjects used certain standard words: 'spread-out,' 'spacious,' 'formless,' 'without centers.'"

Lynch argued that the "art of urban design" should work to create a vivid and coherent environmental image. This allows the city to be legibile, a challenge for places welcoming visitors and residents from backgrounds that may have differing standards of urban legibility.

But it's a challenge that cities must embrace, not just for ease of navigation or individual emotional attachment to place. As Lynch wrote, "Even awkward 'beautification' of a city may in itself be an intensifier of civic energy and cohesion."

In Houston, there is already a potential network of landmarks that the sprawling, diverse city might cohere around: the bayous.

For years, the bayous were treated as obstacles and largely neglected. Through initiatives like Bayou Greenways, the city is increasingly turning its attention to the waterways.

Reclaiming them is also a critical part of creating a more resilient Houston. After Hurricane Harvey, Jim Blackburn, co-director of Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters (SSPEED) Center, argued that all residents should know their watershed as a way to create "flood-literate" citizens.

It would also mean understanding how actions upstream can cause consequences downstream and it would situate communities along throughlines crossing the city's expanse. Some scholars have investigated the link between a strong place identification and a community's environmental attitudes.

By simply making the systems of waterways more "legible," the city could help strengthen connections and a sense of shared responsibility— essentially extending the cognitive maps of each Houstonian to include a few more Houstonians.