Commentary

From the very beginning, San Antonio’s black community has shaped the city’s history. In celebrating our 300th anniversary, it is important that we revisit these beginnings and analyze how the San Antonio we know today came to be.

No history is ever complete, but knowing the diverse tapestry of San Antonio’s origins is ever-important. To this end and in the celebration of the Tricentennial, we must take a close look at the black community’s contributions to San Antonio.

Located on the near-Eastside of San Antonio, close to Sunset Station, is St. Paul Square. This area was the center of black life in San Antonio for many years, its name derived from the St. Paul Colored Methodist Church that was established nearby on Center Street.

One of the leaders in the African-American community during Reconstruction was Lafayette Walker, a veteran of the Civil War and a black union soldier who pressed the idea of making political deals that would provide infrastructure improvements for the black community.

Established in 1866, St. Paul Methodist Church is the oldest black church still in existence in San Antonio. The church was active in civil rights for blacks, with leaders like Rev. Matthew “Mack” Henson carrying on the fight. Like Walker, Henson advocated for political candidates running independently. This helped create the nonpartisan city elections we have in San Antonio today.

Mount Zion First Baptist Church was founded in 1871 by 22 freed slaves. The church was located on Santos Street in the Baptist Settlement, a large section in the southern sector of San Antonio that extended from near Commerce Street in the north, to around Labor Street in the south. It was bounded on the west by South Presa Street, and on the east by present-day Interstate 37.

By 1927, Mount Zion had moved from the heart of the Baptist Settlement, which was on the eastern side of the San Antonio River. In later years the church would be active in the 1960s Civil Rights movement under the leadership of the Rev. Claude Black. Today, Mount Zion is located at 333 Martin Luther King Dr.

The Canary Islanders who arrived in San Antonio in the 1700s included white Spaniards and blacks. This is noted in Kenneth Mason’s 1997 research, which provides evidence that darker-skinned Canary Islanders – people of color quebrado, or broken color – were forced to live east of the river.

Mason writes:

“Racially conscious Islanders associated blacks with slavery and lower-class status. Class or ‘castas’ designation established social standing, and persons identified ‘whites’ were held in higher esteem than the darker Indians and blacks. Islander attitudes reflected these views, and physically dissociated themselves from the darker residents. A separate community, Villa de San Fernando, was established by the Islanders on the west bank of the San Antonio river, leaving Villa de Bejar, east of the river, as the resident [sic] of the blacks, mission Indians and the racially mixed.”

The San Antonio River served as the borderline of segregation during this period, establishing racial spaces and boundaries. That is how the Eastside became the black section of town and the future home to San Antonio’s African-American community.

In his classic 1989 work, An Empire for Slavery, Randolph Campbell documents the approximate number of slaves held in Bexar County across various time frames. In 1855, Bexar County recorded on its tax rolls 979 black slaves in the area. By 1864 that number had increased to 1,193.

We know from historical records (City Directory of 1855), that slaves were held and sold by at least three San Antonio mayors and many other city officials. Well-known historical figures in San Antonio who were pro-slavery include José Ángel Navarro, Juan Seguín, and Mayors Samuel Maverick, John M. Carolan, Charles F. King, and Francis Giraud.

Slave sales took place at the Menger Hotel, along the Salado Creek, the San Antonio River, and other areas near the present City Hall. According to Mason, slaves in San Antonio were sold at the “auction houses of such well-known names as Henry Burns, John M. Carolan, Charles F. King, George Collamer, WD. Greenwood and Company, J. N. Henriques, E. J. McLane, and Francis Giraud.”

Having been long established, the eastern side of the river remained the black part of town and was solidified by the advent of the railroad coming to San Antonio. Additionally, blacks came to occupy smaller enclaves in the northern and western sections of San Antonio that included Newcombville in the San Pedro Park area, and its westward expansion toward Zarzamora Street on the city’s Westside. But the Eastside remained the principle location of the largest black community.

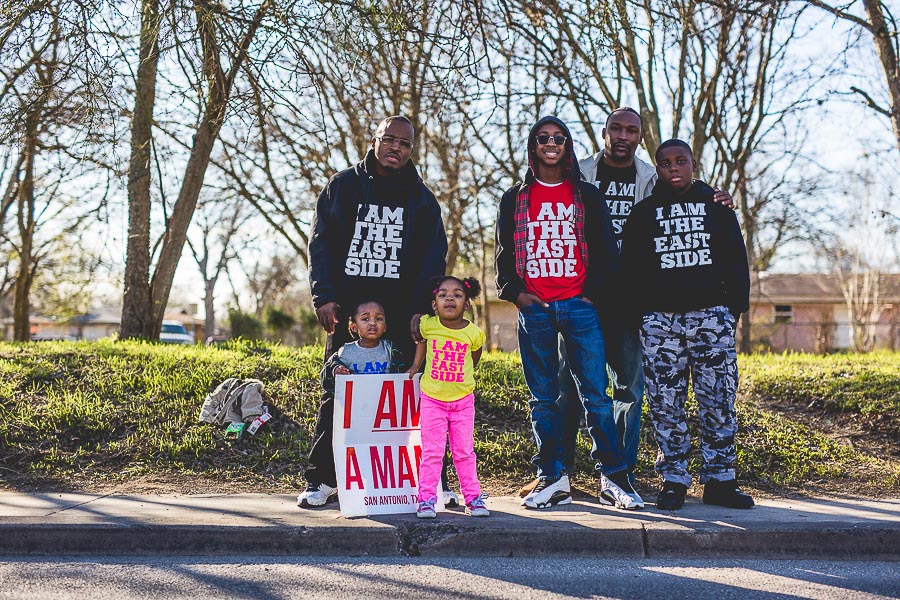

Through Jan. 20, Dreamweek will host a series of programs aimed at promoting tolerance, equality, and diversity in our community. This year, these programs are part of the Tricentennial calendar of events. While we look back and study San Antonio’s history, we must also work to create the kind of city we want in the future.

Mario Marcel Salas is a former member of the San Antonio City Council and current member of the San Antonio Tricentennial Commission.

This story was originally published by The Rivard Report.