When Richard Carranza was selected as the new superintendent for Houston Independent School District over the summer, he said he got at least a dozen emails from realtors offering to help with his move from San Francisco. They promised to find him a home “near a good school,” Carranza remembered.

“It really offended me,” he said, speaking to a crowd of parents and community members at Third Ward’s Blackshear Elementary.

Since his arrival, the former Superintendent of the San Francisco United School District has embarked on a weeks-long “listen and learn” tour, visiting 21 schools across the district, the largest in the state and more than four times as big as his previous district. On a recent Saturday in October, he spoke in the heart of Third Ward, with HISD board member Jolanda Jones introducing him before Carranza fielded questions from the community.

“I’m a huge supporter of his,” Jones said of the district's new leader.

Carranza was approved by the board unanimously. A teacher-turned-administrator originally from Tuscon, Ariz., Carranza has made a strong first impression in his first month and a half in office. Carranza’s appointment marked a milestone in Texas, where the majority of public schools students are Hispanic: Today, the districts in the state's eight largest cities all have Latino superintendents. On the day he signed his contract with the district, Carranza joined a band of mariachi student-musicians, singing along. On his tours of the schools, Carranza, who helped create a bilingual diploma in San Francisco that recognizes a student's mastery of two languages, conversed cheerfully with students in English and Spanish.

“When I began kindergarten in Tuscon, I was a Spanish speaker,” he told the crowd at Blackshear. His parents trusted the public schools. And so does he, he said.

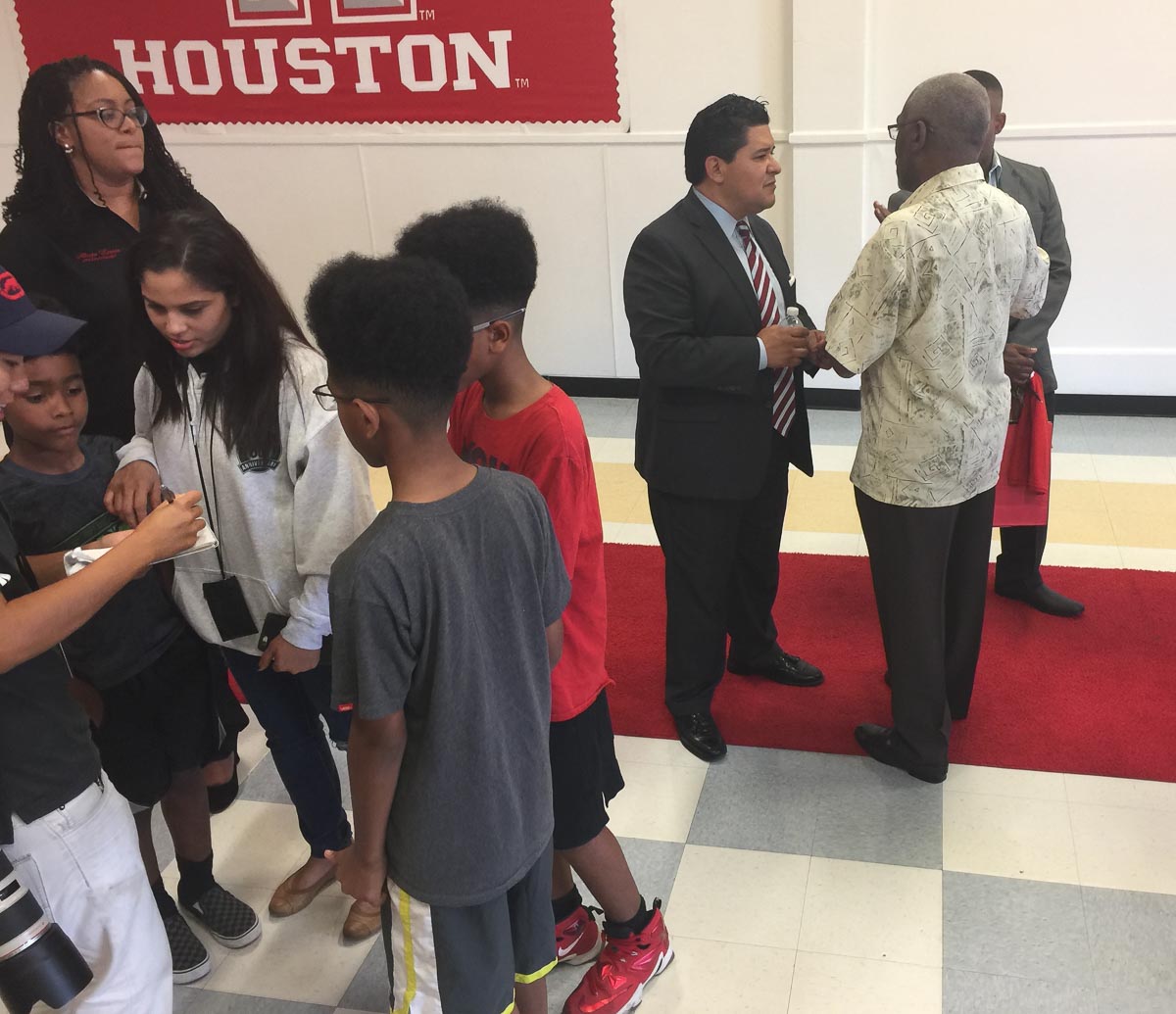

Richard Carranza visited 21 schools in September and October as part of a listen and learn tour. Photo by Leah Binkovitz.

Richard Carranza visited 21 schools in September and October as part of a listen and learn tour. Photo by Leah Binkovitz.

But in Houston, that trust is not always there. In a district where school closures tend to disproportionately impact black and poor students, according to an analysis by the Kinder Institute's Houston Education Research Consortium, community members attending the forum at Blackshear Elementary spoke of a strained relationship between the district and historically disadvantaged communities. “What can I do as a parent to make sure this school stays open?” asked one mother, her young children playing by her feet.

Even among board members, the relationship is, at times, strained. Recent high-profile votes, including the renaming of several schools with Confederate namesakes and banning suspensions for kids in the second grade and younger, divided the board and the larger community. Just weeks after Carranza started, he and the school board were ordered by the Texas Education Agency to take leadership training, part of an effort to help the governance of districts with struggling schools.

But those divides echo deeper divisions across the district’s schools. Only 6 percent of African American students and 7 percent of Hispanic students are considered college-ready based on their SAT and ACT results, while 53 percent of white and Asians students are, according to the district. Dozens of campuses failed to meet state standards in the 2015-2016 school year, including Blackshear Elementary.

Carranza will have to bridge those divides both on the board and for the district. But many are optimistic about his tenure.

“He really wants to know what’s out there,” said Juliet Stipeche, the city’s recently appointed education czar and a former member of the school board. “He understands you can’t take this cookie cutter approach.”

This is the first time Rhonda Skillern-Jones has been a board member during a transition to a new superintendent but she said, as a longtime parent in the district, "I don't think there's been another superintendent that really values community input the way I've seen him demonstrate."

At Blackshear, he told the crowd, “We’re not going to talk about failing schools,” but historically disadvantaged schools. He touted his work in San Francisco, including introducing a mariachi music program, investing to close achievement gaps and introducing culturally relevant curriculum. But those efforts were not without pushback.

“Equity is not a conversation people wanted to hear,” Carranza said. He told the crowd of one father in San Francisco who complained that the district was giving too much money to struggling schools and not his daughter’s school. “I guarantee your daughter a seat in that school I’m sending money to. Call me,” he remembered telling the man. “I’m still waiting,” Carranza told the crowd.

In some ways, Carranza faces bigger challenges. Only 54 percent of students in the San Francisco United School District qualify for free and reduced lunch, a measure of economic disadvantage, compared to nearly 80 percent in the Houston Independent School District. San Francisco’s public schools are 13 percent white, 36 percent Asian, 27 percent Latino and 8 percent African American, according to the district’s latest numbers. Houston, meanwhile, is roughly 8 percent white, 4 percent Asian, 62 percent Hispanic and 24 percent African American.

“San Francisco is different from Houston,” said Stipeche. “But he deeply cares about issues of equity.”

Parents, community members and longtime residents turned out to meet with the new HISD superintendent Saturday, October 8. Photo by Leah Binkovitz.

Parents, community members and longtime residents turned out to meet with the new HISD superintendent Saturday, October 8. Photo by Leah Binkovitz.

In recounting his experience with realtors eager to find him a home near “a good school,” Carranza said he knows schools deal with hugely different realities, a fact that gets lost in high-stakes, standardized testing environments. Kashmere High School, which has failed to meet state standards seven times and now has a state-appointed supervisor, is a school that gets “no credit in the testing culture,” he told the audience. But he said when he visited the campus, he saw a principal who knew everyone’s name and wraparound services meant to support the students. “What I saw at Kashmere High School was incredible,” he said.

Kashmere High School is not in Third Ward but people there felt connected to the fate of the school where the majority of students are African-American and economically disadvantaged. “You’re a man of color,” Rufus Browning told Carranza, “so I’m sure you can relate.”

Indeed, his colleagues feel his ability to connect will be a strength in his new position.

“He is an accomplished leader with a deep understanding of how to connect with the community,” said Nancy Lewin, executive director of the Association of Latino Administrators and Superintendents, for which Carranza serves as a board member.

Lewin hailed his appointment as an important step in furthering the representation of Latinos in superintendent roles. Today, they make up only about 2 percent of all school district superintendents across the country, according to a 2010 report by the AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “He possesses exceptional attributes and preparation to lead a culturally diverse community,” said Lewin. “He is dedicated to providing the highest quality education for all students.”

Skillern-Jones said with big financial challenges and looming questions about equity with a district-wide study underway examining attendance boundaries and the impact of magnet programs, she's confident that Carranza has the experience necessary to navigate those issues. "He understands our precarious financial situation, and he comes from a background of being able to leverage community partners and businesses," she said.

At the same, she said, "I also think he understands equity (and) is willing to look systematically about where we’re putting our resources and how we allocate scarce dollars."

Toward the end of the meeting at Blackshear Elementary, after the cheerleaders and marching band that greeted Carranza earlier have gone, residents shared their concerns. A man from Sunnyside asks why so many schools are without counselors. A mother worries her child's school will be closed. And a woman describes how she believes magnet programs have strangled neighborhood schools.

“You have an amazing challenge,” she tells him.