Founder of Islam in Spanish, Jaime Mujahid Fletcher stands in the center's exhibit that chronicles Spain's Moorish history. Photos: Leah Binkovitz.

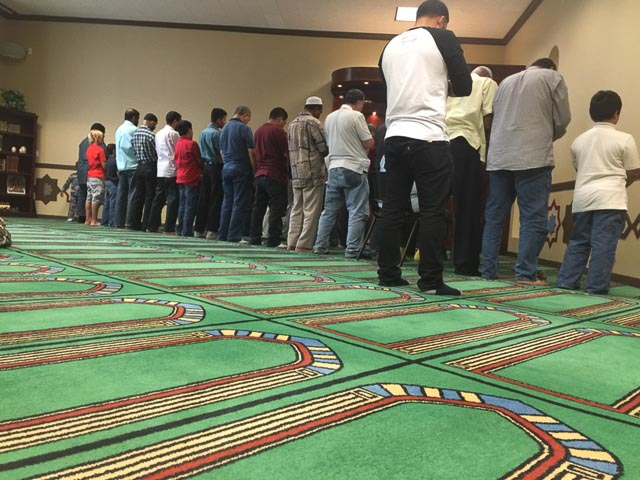

It’s a typical Friday afternoon service inside the mosque on the western edge of Houston. Children slip their shoes off outside the worship space and run ahead of their parents as they find a spot on the vibrant green carpet inside. Women in the back. Men in the front. Everyone facing East.

People greet each other with the customary “Assalamu alaikum,” but what follows is less typical.

“Cómo estás, hermana,” the women say to each other as they embrace. And to the men, “hermano.” A donation box asks for money for Qurans in Spanish to send to Latin America.

Located in the shadow of Highway 6 passing over the Westpark Tollway, the organization Islam In Spanish opened Houston’s only Spanish-language mosque earlier this year, called the Centro Islámico.

Already 15 years old, Islam in Spanish has produced hundreds of video programs -- produced in Spanish and available online as well as on local public television channels -- about the religion. It also distributes information via CDs and other means in order to reach Spanish-speaking populations across the world.

But it makes sense that’s it here, along what may be Houston’s most diverse thoroughfare, that Islam in Spanish came to be. A parade of strip malls passes by the windows of the cars speeding up and down six lanes of traffic on Highway 6 near the mosque. All the big chain stores can be seen -- but so too can the diversity of the area.

Opened inside a nondescript office building, Islam In Spanish shares a parking lot with a small Muslim school and sits across the street from an African food market and another mosque. Down the street, there’s a Fiesta, the now-defunct Bollywood Cinema 6, and Mercado 6, a sprawling indoor flea market.

“I can’t think of a better location,” said Jaime Mujahid Fletcher, founder of Islam In Spanish. Houston is home to growing Muslim and Latino communities, and -- though much smaller than either -- Fletcher says the area also hosts one of the nation’s emerging Latino Muslim communities.

He estimates there are roughly 1,000 Latino Muslims in the Houston area. But with its new center and a Latino Muslim convention -- with programming in Spanish -- planned for December at the George R. Brown Convention Center downtown, Islam In Spanish hopes to become an international hub for the Latino-Muslim movement.

Shared history

Latino converts are hardly unique. About half of all American adults have changed their religious affiliation at least once in their lifetimes, according to Pew Research. And of Muslims born in the United States, an estimated 10 percent are Hispanic, compared to only 4 percent of Muslims born in another country. There are growing communities of Latino Muslims in New York City, Miami, Chicago and Los Angeles.

When Hjamil A. Martínez-Vázquez, a religious studies scholar, wrote about Latino Muslims in his 2010 book, Latina/o y Musulmán: The Construction of Latina/o Identity among Latina/o Muslims in the United States, he estimated that there were between 50,000 and 75,000 Latino Muslims in the United States, describing the community as still emerging and made up largely of converts who tended to be women.

Though exact counts are hard to come by, Martínez-Vázquez writes, "what becomes clear is that, after they convert, U.S. Latina/o Muslims are forced to reconstruct their identifies." They can be accused of "trying to be Arab," as more than one member of Islam in Spanish put it, or met with anger from family members.

Fletcher argues these common experiences are part of the reason it's so critical for Latino Muslims to share their stories with each other. One way many converts seek to construct a new identity that has roots in both Latino and Muslim culture is to look to history, according to Martínez-Vázquez.

Indeed, visitors to the center pass by painted arches reminiscent of Moorish architecture from Al-Andalus, as the Iberian peninsula was known when it was under Muslim rule during the medieval period. A small display remembers the contributions of this era, from math and science to architecture and culture. Fletcher says this era represents a Golden Age for the Muslim faith and provides roots for Latino converts. Martínez-Vásquez describes this linking of a Muslim and Latino past as an act of liberating cultural memory. For Fletcher, it was about uncovering an identity he knew little about.

Islam en Español

Fletcher said when he converted to Islam in 2001, after tumultuous teenage years marked by gang violence and drinking, his parents were confused by his decision. And when he looked for books in Spanish that could help explain Islam, he was shocked by how little was out there. “When I started going to bookstores, they didn’t have anything,” said Fletcher, a native of Colombia.

So he made a CD in Spanish that could explain Islam to his family, as well as his in-laws, who were confused that he and his wife were “trying to be Arab.”

The CD worked, and both families began to accept Fletcher and his wife's decision to convert. In fact, many of their family members eventually converted to Islam as well. After the attacks on September 11, he started getting requests from religious and civic leaders to speak around town, serving as a sort of intermediary for a religion with which many, at the time, were unfamiliar.

“I began to see Islam was a way for me to not only benefit myself but to learn to work with people from different backgrounds,” said Fletcher. The Muslim community, he said, embraced his efforts. And the Latino community largely met him and other Latino Muslims with curiosity. “When we share it,” he said, “all of a sudden, people find similarities" between the two cultures, like the importance of family and hospitality.

Cultural experience

Sitting in the center’s live-streaming studio, Fletcher said he feels fortunate to be here, so close to where he grew up. “To be in an area where in the past we felt we didn’t have much to contribute,” he said, “to come back; it was important to us.”

When the center opened in January, Latino Muslims from across the country came including some Puerto Rican Muslims, who represented one of the early waves of Latino Muslims in New York. The group was exposed to the faith through the Nation of Islam in Spanish Harlem. Fletcher affectionately calls these the “OGs,” or original gangsters. As different as their backgrounds are, he said, they have some basic things in common, which is why it was so important to host their own convention specifically for Latino Muslims.

“There’s still not a lot of programs geared toward the Spanish speaking population,” said member Nahela Morales, who believes the upcoming convention could serve as a place to discuss some common struggles and challenges. “We may be dealing with a family member who is kicking us out because of our religion,” she said.

For Cinco de Mayo, the center held a carnival with halal Mexican food. At community celebrations, the kids hit piñatas and eat tamales. Most of the congregants are Mexican American, matching the demographics of the Houston area, but many are from elsewhere, including Colombia and El Salvador.

“For us to be Latino Muslims and have this place that is 5,000 square feet to be able to offer the first sermon in Spanish adding some Arabic from the Quran and do a summary in English,” said Fletcher, “it gives us great joy.”

"I'll always be your family"

For many, the path to Islam can be slow. And when a decision to convert is finally made, it can be difficult to share with family.

Morales knew she believed in God. But her faith was tested. Morales, now 40, was born in Mexico and immigrated to California when she was just four years old. In her 20s, after the birth of her son, she said she was searching for stability. “I would turn to God and when I felt God was not hearing me, I would turn to the Virgin of Guadalupe,” she said, referring to the figure of the Virgin Mary who, as the story goes, appeared before Juan Diego, an indigenous peasant who later was granted sainthood, in 16th century Mexico.

“Just guide me,” she’d plead, as she navigated her way through a painful divorce.

She moved to New Jersey, just outside New York City, attracted by the diversity and the distance from her old life. It was three months before September 11, 2001.

Like so many after the attacks, Morales was confused. “Who are these Muslims?” she remembers thinking. “What are they doing here?” She bought a Quran and found something entirely different from the image created by the attacks: peace for herself and a way of life she hoped would be good for her son. “I found what I had been looking for, for many, many years.”

She slowly started befriending Muslim women online from across the world, fascinated by the religion’s reach and strength. “They didn’t even know me and they were calling me sister,” she said. But it took her awhile before she entered a mosque in her home of New Jersey. “I was petrified, I didn’t know what to expect.” At her first visit, she worried that too much of her hair was showing beneath her scarf. The imam, sensing her nervousness, told her she didn’t need to wear a covering because she wasn’t Muslim. “You’re just here to learn,” she remembers him saying. That was enough to put her at ease. A couple years later, she decided to officially convert, wearing a head covering all the time -- and not just in the mosque.

But telling her family proved more difficult. “I think at the beginning they felt a bit betrayed,” she said. What she feared might happen, did.

On a visit to Mexico City to visit family, she got into a fight with her cousin. “She yanked my hijab off,” said Morales, now the brand ambassador for Islam In Spanish. Her cousin kicked her out. “But then I came back,” she said. “I told them, 'I’ll always be your family.'”

Everybody is welcome

This year, when member Juan Pablo Osorio went to Mecca, the holy pilgrimage site where Muhammad was born, he encountered just one other Latino: a cleric also from Houston. But they were greeted warmly by the other Muslims who had made the trip. "They're very happy to find Latinos coming into Isam and being what they see as serious about it," he said.

Like Fletcher, Osorio is originally from Colombia but moved to Alief on the west side of Houston with his family when he was a child. “My first day in Houston in sixth grade, in my [English as a Second Language] class, I remember my teacher was wearing a hijab,” he said. “There were people who spoke Arabic, Japanese, Vietnamese, Russian,” and, like him, Spanish.

Osorio loved the diversity of his new community. Later, when he joined the Marine Corps, he’d tell people he was from Colombia. They’d protest and say he was Texan. But he replied, insistent, “I am from Colombia and I am from Texas,” proud to claim both.

When he was deployed, first to Iraq in 2007 and then to Afghanistan in 2011, his curiosity turned to Islam. As different as the two countries were, he saw a similar hospitality that he credited to their shared religion. But it wasn’t until meeting Fletcher when working together on a film project that he decided after years of study to convert to Islam a year ago. He left his sales job with AT&T to start working with Islam In Spanish’s video production team while he finishes school.

“Nobody tells anybody here you have to wear a hijab or you can’t have tattoos,” Osorio said. “Everybody is welcome here. We have people all the way from Pasadena or Baytown come here and say their testimony of faith.”

At times, Morales said, people aren't sure what to make of her. In Mexico, she's treated as a foreigner; in Houston, people look at her shocked when they realize she speaks Spanish. But, she said, "I think it’s encouraged not only through our religion, but through our prophet and through the Quran for us to keep our identity, to preserve our culture. We're able to do that here."