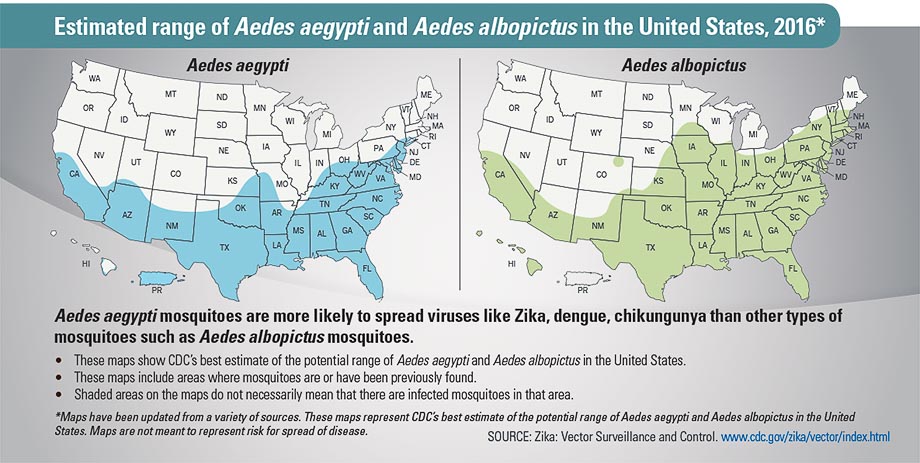

The Gulf Coast is home to the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito during the summer months. Image via The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Gulf Coast is home to the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito during the summer months. Image via The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Update: Public health officials in Harris County reported July 13 they had identified a baby with Zika-related microcephaly, marking the first such occurrence in both the county and in Texas.

Public health researchers say Houston -- with its mix of poverty, rainy conditions and world travelers -- is particularly vulnerable to the spread of the Zika virus, the mosquito-borne disease that has dangerous effects on the fetuses of pregnant women.

At a recent conference of public health experts and researchers at Rice University, Peter Hotez, a fellow in disease and poverty with Rice University's Baker Institute, described the situation in Houston and the U.S. Gulf Coast as a "perfect storm" of conditions that could facilitate the next wave of the Zika virus, a condition the World Health Organization has declared a health emergency.

"Our area is highly vulnerable," Hotez said of Houston, adding that the depth of Houston's poverty rivals any other part of the country. "This is not hard to find," he added, of the conditions that facilitate mosquito bites and breeding. "Houses with no window screens, discarded tires filled with water, especially now after a lot of rain, plastic containers. This is mosquito heaven."

Stopping the spread of Zika will take more than research. It will take prevention and what Hotez calls "house to house environmental cleanup," particularly in poor communities.

"Texas seems to be uniquely vulnerable," added Hotez, who also serves as dean of the School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine. The threat, he said, isn't just Zika but also a slew of other emerging and neglected diseases.

His comments come as concern about Zika have come closer to home in recent weeks after the disease's initial spread in Brazil. In April, a 70-year-old man in Puerto Rico died, marking the first U.S. Zika death. Last month, a Houston woman who previously lived in South America tested positive for Zika. And this month, the Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center, which provides blood to medical facilities across the Texas Gulf Coast, will start testing blood donations for the virus, the Houston Chronicle reports.

Hotez cautioned that the U.S. shouldn't feel like it's immune from the mosquito-borne illnesses just because it's a wealthier nation.

"Most of the world's neglected and emerging infections are not necessarily in the world's poorest countries," said Hotez. Instead, he said, diseases like Zika and Dengue are "mostly occurring in the 20 wealthiest economies." The populations that are most vulnerable are the poor in cities like Houston, a major destination for international travel and migration at the heart of the phenomenon, he said.

Houston should also expect more cases as the weather warms, he said. "It's the poor living among the wealthy that are accounting for these diseases," he added.

The risks of the Zika virus were poorly understood when patients in northeastern Brazil first began complaining of aches and fevers. It wasn't until doctors confirmed a link between the mosquito-borne illness and microcephaly, a condition that causes birth defects, that the severity of the virus began to be understood. Lt. Col. Wendy Sammons-Jackson, of the the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, said although Zika was on public officials' radar along with malaria and HIV, it wasn't a high priority. "There wasn't a great understanding of what that impact would be," she said during the panel.

Closer to home, compounding the threat in Houston is the fact that the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito that helps carry the Zika virus is common in the Gulf Coast during the summer months. Cities in south Florida and Texas are particularly vulnerable to diseases carried by the mosquitos, including dengue, which has flared up in Texas in recent years. Known for the deadly diseases it carries, Aedes aegypti was once eradicated from many of the countries now battling it again.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito. Image via CDC.

The Aedes aegypti mosquito. Image via CDC."By 1962, 18 countries plus several islands in the Caribbean announced they had eradicated the mosquito, thanks to hefty doses of the insecticide DDT, military-grade organization and plenty of funding to train personnel and buy equipment and supplies like DDT," according to the International Business Times. "In Brazil, the process involved 617 million house visits from 1931 to 1958."

But the U.S. Gulf Coast was not part of the massive effort, according to Hotez. "We've historically refused to control Aedes aegypti on the Gulf Coast," he said, noting that many Latin American countries, ironically, had actually complained about that shortcoming as the mosquito continued to survive and eventually reemerge in those countries after funding decreased.

Eradicating the species now, while possible, would require significant investment, Hotez said. "It's doable, it has been done," he said, but, "we're not seeing any international will to do this."

The spread of the virus has prompted the World Health Organization to declare a health emergency. Image via The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The spread of the virus has prompted the World Health Organization to declare a health emergency. Image via The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.There are still many unknowns about the disease as researchers work to create a vaccine and look to the federal government for funding. The Galveston National Laboratory at the University of Texas Medical Branch is one of the institutions currently working on the virus and diagnostic tests.

"We can process about 1,000 specimens in a 24-hour period," said James Le Duc, director of the laboratory. Both Le Duc and Hotez warn, however, that it will be some time before the the Food and Drug Administration sign off on any tests or vaccines for Zika partly because of the the many regulatory precautions taken with the target population: pregnant women.

"When you're trying to do safety testing," explained Hotez, "what's the highest bar of all? Women who are pregnant or thinking of being pregnant."

A state by state look at reported Zika cases. Image via The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A state by state look at reported Zika cases. Image via The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Efforts to secure emergency funding for both research and prevention has stalled in Congress, after the president asked for some $1.9 billion in funding. In lieu of congressional support, the White House redirected $589 million to put toward the fight, most of which came out of funds originally for Ebola. But health officials and politicians are stressing the need to create a source of stable funding for future health emergencies.

"That's not the most effective way to do it," Congressman Gene Green, who represents the 29th District including parts of north and east Houston, said of the administration's decision at the panel. He noted Zika is merely one of several emerging diseases threatening Texas.

"All of these issues require emergency involvement," Le Duc added.

As cases of Zika virus inch north, Hotez said he expects Haiti to be the next country hardest hit by the disease. Like northeastern Brazil, it shares critical characteristics that help accelerate the spread of this and other viruses including poverty and crowding.

Harris County Public Health and Environmental Services is tracking reported cases of Zika and its mosquito control division is working to head off the virus. "It's a matter of when, not if," the agency's executive director Umair Shah recently told Wired magazine. As was the case with Ebola, Shah told the audience at Friday's conference that it's important to do on-the-ground community outreach, particularly in Houston's international communities. "We cannot spray our way out of this," he said, "We have to engage our community and partners."