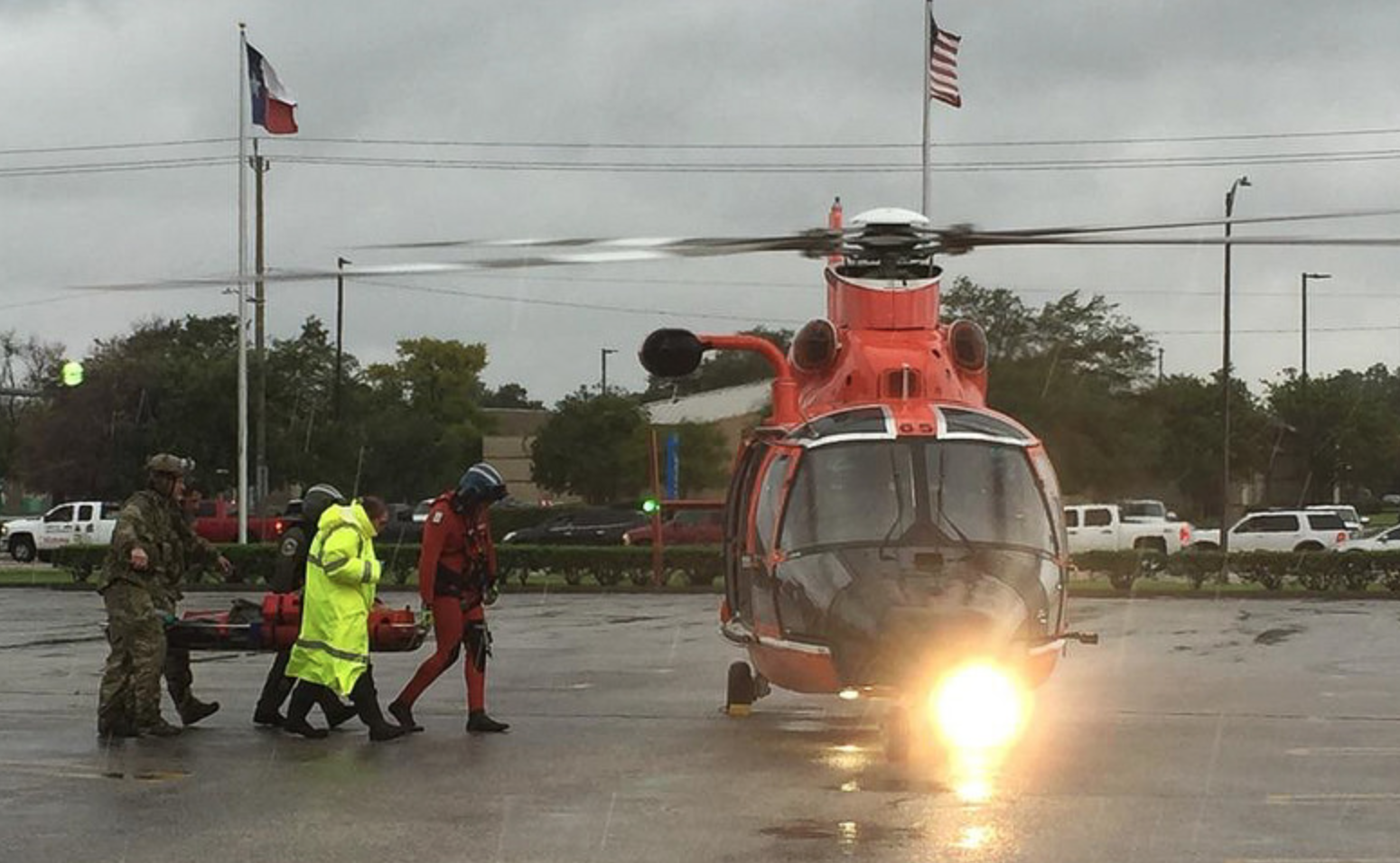

The health care and public health community can claim several victories in the wake of Hurricane Harvey: the relatively low death toll, the success of the investments made to fortify the Texas Medical Center and the rapid response to the elevated risk of mosquito-borne illnesses after the storm.

But for some health professionals and officials, the storm also laid bare, and potentially exacerbated, the failings of the health care system and public health in the region.

"We can pat ourselves on the back a lot," said Elena Marks, president and CEO of the Episcopal Health Foundation at a panel discussion hosted by the Texas Tribune Thursday. "We get an A+ in health care for some people, and truly only for some people. We get a really poor grade in this community in building the kinds of human capital infrastructure that help people before, during and after in building resilient communities."

Lessons Learned

In 2001, Tropical Storm Allison proved particularly disastrous for the Texas Medical Center. Many of its "facilities flooded, forcing patients to be evacuated, sometimes in the dark," recounted Rachel Arndt in a recent Modern Healthcare article. "Animals in the Baylor College of Medicine's basement died in floodwater."

With millions in investments following that storm, many of the hospitals there installed floodgates, moved generators out of the basements, added water pump systems and made other preventative changes. And it proved largely successful during Harvey. The Tuesday after the storm hit, all of the 23 hospitals in the medical center were operational except for Ben Taub Hospital, which experienced flooding and had to stop accepting new patients.

"There has been an incredible amount of investment that has been made by our community in our health and health care system," said Umair Shah, executive director of Harris County Public Health. Of the more than 120 health care institutions in the county, including nursing homes and other facilities, Shah said fewer than 10 percent of them had to shut down or evacuate patients during the storm. On the public health side, Shah said, "The county…really worked hard also in making sure there was an incredible amount of investment on the governmental side. All that comes together in investing for a community when it has a crisis as large as Hurricane Harvey."

Part of that investment went toward an aggressive anti-mosquito campaign following the unprecedented rain event. The county worked with the state and federal government to conduct aerial spraying to curb the risk of mosquito-borne illnesses like West Nile virus. A total of more than 6.7 million acres were treated across 29 counties in the affected region, according to the state health department.

Persistent Gaps

Despite the investments and coordinated response, there were significant gaps, like the largely unregulated operation of dialysis clinics that left many patients stranded during the storm. "They just closed and went home," said state representative Sarah Davis, a Republican who chairs the House Appropriations Sub-Committee on Budget Transparency and Reform and said she's interested in considering more regulation for dialysis centers.

There were also complaints from residents and environmental advocacy groups that toxic water and elevated emissions around the Ship Channel were largely going undocumented and ignored by health officials.

And then there are the looming challenges the storm left in its wake, including a likely surge in mental health issues. Before the storm the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute estimated that more than 300,000 children in Harris County needed mental health services and experts expect that number to climb following the storm.

"We have people who live under toxic stress day in and day out," said Marks. "If we use Harvey as an excuse to look at this, I guess that’s good but we have a much bigger problem."

Funding Concerns

When Shah looks at the federal funding that's been approved so far and the conversation about future rounds of funding, he said he's concerned with what he sees. "The initial pass came," he said, "and it was really mostly around [Federal Emergency Management Agency] and [Housing and Urban Development] funding. There was really no public health funding there. The thought was eventually in the second or third pass, but increasingly I'm concerned that I'm not seeing anywhere this notion of public health."

But even then, Marks said, funding has to prioritize health and not just medical services. "We are obsessed with investing in medical services and we are doing that at the expense of investments that actually produce better health outcomes," said Marks.

"While Americans are clearly willing to invest in the health of suffering communities, our tendency to do so only in the immediate aftermath of tragedies like Harvey means that the benefits of those donations will likely be minimal," argued Sandro Galea, dean of the Boston University School of Public Health in a recent Harvard Business Review article. "By effectively ignoring marginalized communities until after they have been devastated by a natural disaster, we all but ensure that the human toll will be higher and the damage costlier when the storm finally arrives. A far better strategy would be to spend money to improve the conditions of vulnerable communities well before the worst happens, mitigating in advance the costs of tragedy and helping to build a healthier world."

With some funding already making its way to local organizations, Marks said she wants to be sure the need to respond quickly is balanced with the need for good data to be sure funding reaches people in need.

"The way that this community has improved its ability to withstand storms in terms of health care delivery is remarkable," Marks said. "We are really good at disasters.” But she cautioned, those services required access that many didn't have during the storm and still don't after.