When the Texas Supreme Court handed down its highly-anticipated verdict in the seventh challenge to the state’s school financing system since the 1980s, it dealt a blow to the more than 600 school districts acting as plaintiffs in the largest such lawsuit to date.

Nearly two-thirds of the state’s school districts, with a wide range of economic characteristics, argued that the state's current funding formulas don't provide enough resources to meet state education standards and fulfill the constitutional requirement to teach students though an "efficient system of public free schools."

The plaintiffs also charged that school districts -- even property wealthy districts -- now have to rely so heavily on local property taxes that it effectively creates a state property tax, which is constitutionally prohibited.

The court disagreed on both matters in a 9-0 decision, declaring the system constitutional for only the second time.

A court in retreat

In his opinion, Justice Don Willett said although the system was imperfect, it was not “imperfectible.” But he said such change would have to come from the legislature, which cut education funding by nearly $5.5 billion in 2011, prompting lawsuits from many of the state’s districts.

“I think we have a court in full retreat,” said David Thompson, an attorney who represented moderate-wealth districts including Houston ISD, Fort Bend ISD and Cypress-Fairbanks ISD, among others, in the lawsuit. “(The courts) don’t want to be part of this.”

Though some of the funding was later restored, many in education also question the legislature’s commitment to providing a well-funded system.

“The legislature didn’t need permission from the court to fix these problems,” said Scott Hochberg, an education finance expert who previously served as a Democratic state representative. “I don’t see any added pressure.”

Indeed, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott praised the court for preserving the status quo.

"Today's ruling is a victory for Texas taxpayers and the Texas Constitution," Abbott said in a statement. "The Supreme Court's decision ends years of wasteful litigation by correctly recognizing that courts do not have the authority to micromanage the State's school finance system. I am grateful for the excellent work of the State's lawyers at the Attorney General's Office, without whom this landmark ruling could not have been achieved."

Since the 2011 cuts, the legislature restored some of the lost funding, increased the basic amount allotted to each student in the funding formulas and added $118 million for new pre-kindergarten programs. But many districts argue the fundamental problems remained.

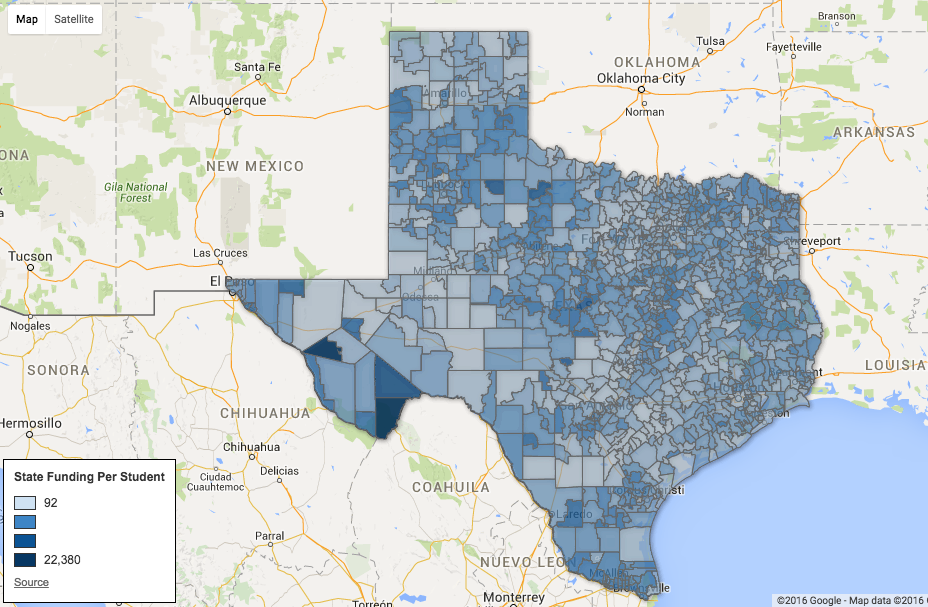

Interactive: Click on each district to see more details about its 2015-2016 funding, demographics and programming. By Leah Binkovitz.

Low-hanging fruit

The court addressed two major topics raised in the suit: one focusing on equity issues and one involving the notion that the state has essentially created a state property tax.

Under the current school funding system, many district find themselves having to tax at or near the state-set cap of $1.40 per $100 of home valuation. Some districts have even successfully received local voter approval to exceed that rate. Even property-wealthy districts have had to raise taxes, they say, because the state uses a program called "recapture" to redistribute some of that tax revenue to less wealthy districts or the state general fund. Thompson thought the evidence that this amounts to a state tax was clear.

"I thought the ... claim was obvious, frankly," he said. "The dependence of the system on property taxes, and the way the state is even using school property taxes for non-education things -- it’s really just a source of revenue for the state budget.”

In the past, Hochberg said when it was argued that some districts had to impose much higher tax rates than others, “that’s always been a trigger for the court saying the system is out of constitutional compliance; it’s not fair to taxpayers and it’s not educationally fair.” But in this ruling, said Hochberg, “we have backed away from the requirement for fairness in the way property taxes are assessed.”

In many cases, districts feel forced to increase their tax rates. But even when they don't, residents often experience rising tax bills -- particularly in the Houston area. That's because tax bills rise as property values increase, even when the rate itself remains unchanged.

But that increased revenue doesn’t always return back to the districts. “The state gets the benefit of the property, and the people in the communities don’t know it,” Thompson said. That money, he said, is “really being used by the state to pay for other things, including non-educational things.”

When recapture began in the early 1990s, explained Hochberg, it was to deal with a handful of property-wealthy districts like, Highland Park in Dallas, becoming their own districts. “It was never intended to be something that hit mainstream districts,” he said.

But since then, the list of districts considered property-wealthy -- meaning property taxes there bring in more money than what the state provides for each weighted student -- grew, adding districts like Houston Independent School District to the list.

Under the recapture system, HISD doesn’t do so well, according to the district.

“Our school district is facing a huge financial crisis,” said Ashlea Graves, the governmental relations director for Houston Independent School District, the largest in the state. Graves said the district is looking at sending the state $165 million in local revenue. She says the district is facing a $100 million deficit as it approaches the next school year, and she blames those recapture payments for the shortfall.

A troubling ruling

Part of the reason recapture hits districts like HISD so hard is the district’s high percentage of economically disadvantaged students and English Language Learners, roughly 80 percent and 30 percent of its student population, respectively.

Though funding formulas include weighted amounts for those students, it isn’t enough to provide the types of programs educators say are needed to bridge the lingering gaps in standardized test performance.

Graves said changing those weights would require a tough legislative fight. “Anything they do next session -- it will be very minimal,” Graves speculated, offering little optimism that the status quo would change.

Under the state’s current accountability ratings system, one of the four indices campuses are graded on is their success in closing those gaps between student groups, which is why Thompson found part of Willett’s opinion so troubling.

“It goes on and on and on about how money doesn’t really seem to make a difference, particularly money spent on poor kids,” Thompson said.

Indeed, Willett acknowledged the testimony provided by numerous school officials and educators about the programs that could help make a difference in closing gaps. But, he concluded, they “did not prove that those gaps could be eliminated or significantly reduced by allocating a greater share of funding to these groups.”

He continues his opinion, saying that in order to provide more funding for programs to educate economically disadvantaged students, it would require taking funds away from programs for other students. He suggested any extra resources put towards those programs might result in decreased performance of students who aren't disadvantaged.

That belief, Thompson said, is out of line with the state’s changing demographics. More than 60 percent of public school students are economically disadvantaged, and the number is growing, he said. “You get no sense of recognition about how critical an issue that is to the future of the state,” Thompson said. Though he noted that other justices' concurring opinions differentiated themselves from that of Willett, the 9-0 decision leaves little room for future challenges.

“We do not today foreclose completely a ruling of constitutional inadequacy as to subgroups,” Willett wrote in his opinion, “but conclude that the showing necessary for such a ruling would have to be truly exceptional.”

Perfecting the system

That leaves it to the legislators to address funding issues. Eddie Lucio Jr., a Democrat and vice chair of the state senate’s education committee, said he views the ruling as a clear call for the legislature to fix "what remains of a broken system."

"I hope when the Legislature meets again, whether next January or in a special session before then, we will consider making needed improvements to the school finance system, including replacing all of the funds lost after the 2011 budget shortfall; increasing the basic allotment; re-examining the weights for English language learners and economically disadvantaged students for the first time in 30 years; and funding the construction of necessary new school buildings," Lucio said in a statement provided by Chris LeSeur, the senator's education policy analyst.

Graves, of HISD, is hoping for those changes too. She saw a glimmer of hope last session in a bill put forward by Jimmie Don Aycock, the Republican chair of the state house's education committee. But he subsequently withdrew the bill, saying he knew it had no chance of making it out of the senate.

"You’ve got a political dynamic that is vastly far to the right,” said Graves, "and then they don’t want to spend any money."

Other techniques

The HISD board is currently considering whether to put the issue of recapture on a local ballot.

If it went before voters and failed, Graves said, the state education commissioner could take portions of downtown Houston -- an area with expensive property and few kids -- and allot it to another district with higher tax rates.

The technique would be an intriguing maneuver. It would allow HISD to take some tax revenue off its books, which could trigger more state funding flowing from Austin. At the same time, the state would still get Downtown's tax dollars.

But as Graves looks at the numbers, and the potential upset to the businesses and loss of tax revenue, she said it doesn’t look like it would help the district in the end -- leaving the district in a familiar position.

“When you talk about property tax relief,” said Graves, “how do you do that when the majority of districts rely on property taxes?”