On the same day that Mayor Sylvester Turner released “Resilient Houston,” the city’s resilience-building strategy that highlights the need to make access to public transit safer and more convenient and the continued expansion of public transportation in the region, Steven Higashide took the stage at MATCH in Midtown to talk about the power of buses.

Higashide is the author “Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit,” a book about the powerful impact fast and reliable public transit — specifically, buses — can have on cities.

“We take 4.7 billion trips a year on the bus in the United States. And yet so many of those trips end up being miserable, slow, crowded and circuitous. But it doesn't have to be that way,” Higashide told the audience gathered for the Kinder Institute’s Urban Reads series. “And it really can’t be that way if we are going to address so many of the most pressing challenges that face our cities. It can’t be that way if we’re going to address the urgent need of climate change.”

Buses can help fight climate change

Transportation is the number one cause of carbon emissions in the United States, surpassing power-plant emissions in 2016 as the top cause. As a nation, our cars, trucks, planes, trains, buses and boats produced 1.9 billion metric tons in 2018. And Texas leads the country.

“If we’re going to confront the reality that transportation is now the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., we have to confront the fact that when we talk about decarbonizing the transportation sector, we’re really dealing with the day-to-day trips we make to work, to school, to the grocery store, to everything we need to live our lives.”

The harsh reality is that addressing climate change means driving less. Higashide used California as an example. To meet its climate goals, he says, every new vehicle on the state’s roads will have to be electric or zero-emission by 2050 and Californians will have to reduce their driving by 15%.

“And that means both in California and across the U.S., we have to build cities and build neighborhoods where we can make shorter trips, and where you have to drive for fewer of those trips. That means robust transportation options.”

METRO as a model for other cities

In his book, Higashide writes about METRO’s 2015 bus network redesign — a complete and overnight overhaul of the agency’s route system. He praises the “blank-slate” approach taken by the transit agency and its strategic planning committee. The redesign has become “famous around the country” and is a blueprint used in other cities.

The director of research for TransitCenter, an advocacy group that promotes improved transit in cities across the country, also praised the potential of the MetroNEXT plan.

“This is really going to be a big deal for Houston because it’s the first, I think, or one of the first times Houston is really talking about bus priority and using this design toolkit of bus lanes and traffic-signal timing and priority, and many other design elements to create bus service that’s fast and competitive with driving,” he said.

Houston has some problems

He also drew attention to some areas related to the use of public transit in the city that need to be improved.

“If there’s one element of that recipe I mentioned before, that perhaps bears for special attention in Houston is the pedestrian experience,” Higashide said.

“This is so clear when you walk around in a lot of neighborhoods in Houston, which is the case in a lot of cities that grew up sort of on the same timeline that Houston did. But the truth is, most bus trips are a walking trip, on at least one end. And you can make a bus fast and frequent, you can make the schedule reliable, but people are not going to experience that as a great trip if it also involves crossing six or eight lanes of traffic, running across the street with no traffic light, having an obstruction in the path or waiting in the mud. That’s really, really important to get a handle on.”

What can riders do to make change happen?

So, what can transit riders in Houston do to get the improvements they want? According to Higashide, it takes advocacy, organization and some help to pull the levers of power.

“When (you look) at other places around the country that have successfully made changes to their bus system, you nearly always find an alliance across sectors. You find advocacy groups and civic organizations outside the government pulling a lot of weight and making the case for better transit. Of course, it’s very important to have elected leaders who are willing to be personal champions for transit. And then you have champions inside the bureaucracies, you know, sort of heroic bureaucrats. You could say people who are willing to really think about how do you set up public processes in a way that makes it easier for these other allies to do their job and make the case that trans is really important in a city.”

But when you don’t have, it’s hard to get the improvements that make bus service better for transit riders, who are “more likely to be low-income people, people of color — the people who are marginalized by our political system.”

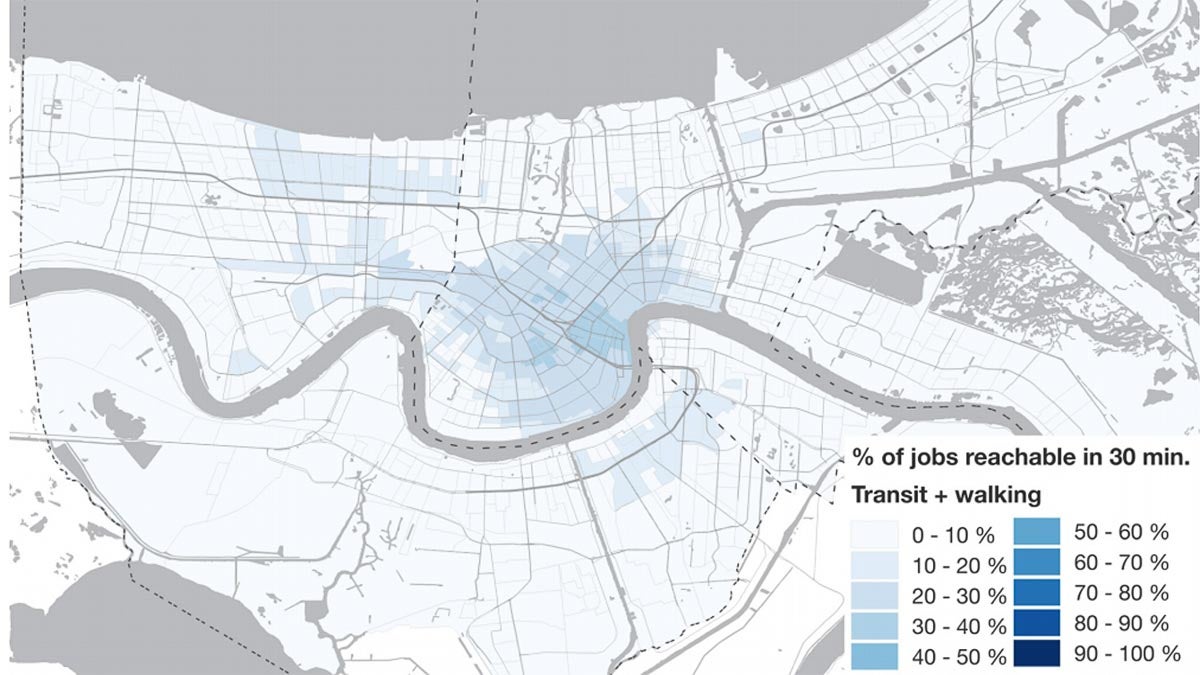

Map showing the area of New Orleans residents can access for jobs if they don't have a car.

Source: Steven Higashide

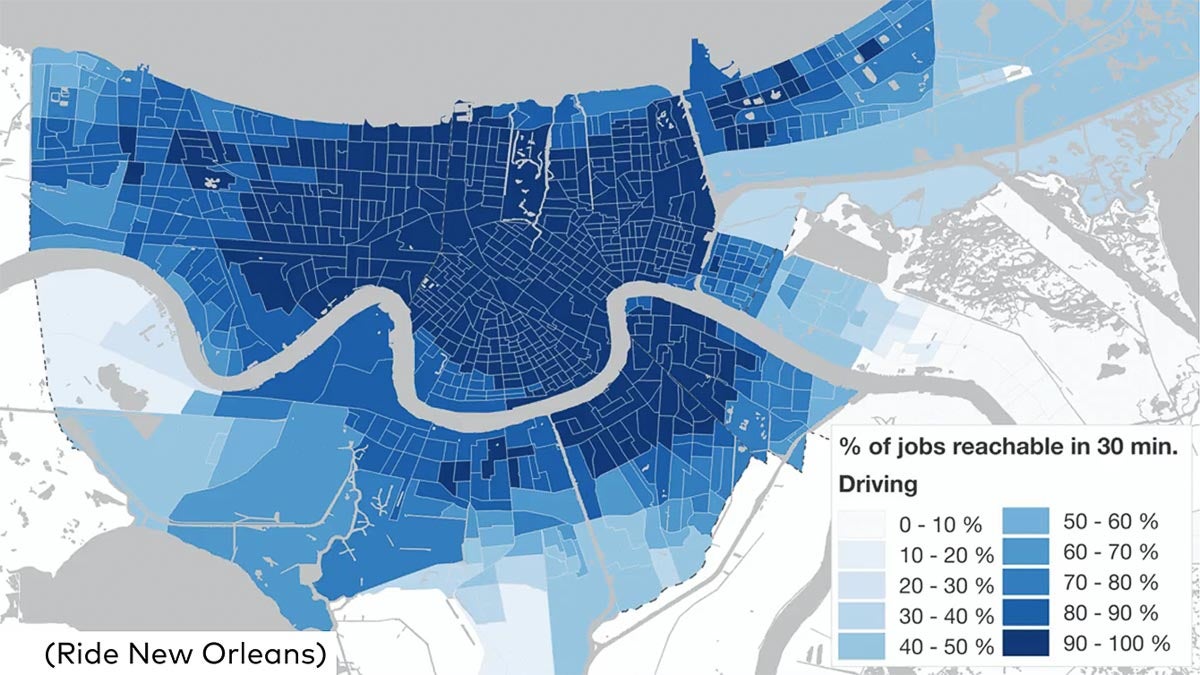

Map showing the area of New Orleans residents can access for jobs if they have a car.

Source: Steven Higashide

Buses as economic drivers

Higashide also talked about quality public transportation as an important weapon in fighting the inequality crisis that’s found in most cities today.

Using New Orleans as an example, Higashide showed two maps: one depicting the size of the area residents could access for jobs if they had a car; the other showing the area accessible to those without a car. There’s a dramatic difference in the size of the area of opportunity accessible to residents with a private vehicle compared to those without.

“It’s just a smaller life. It’s a smaller set of opportunities,” Higashide said of residents who are carless. “That makes it so much harder for low-income people and low-income families to thrive. And you can also sort of flip that over and say that this is an enormous problem for local businesses that need reliable access to the workforce.”