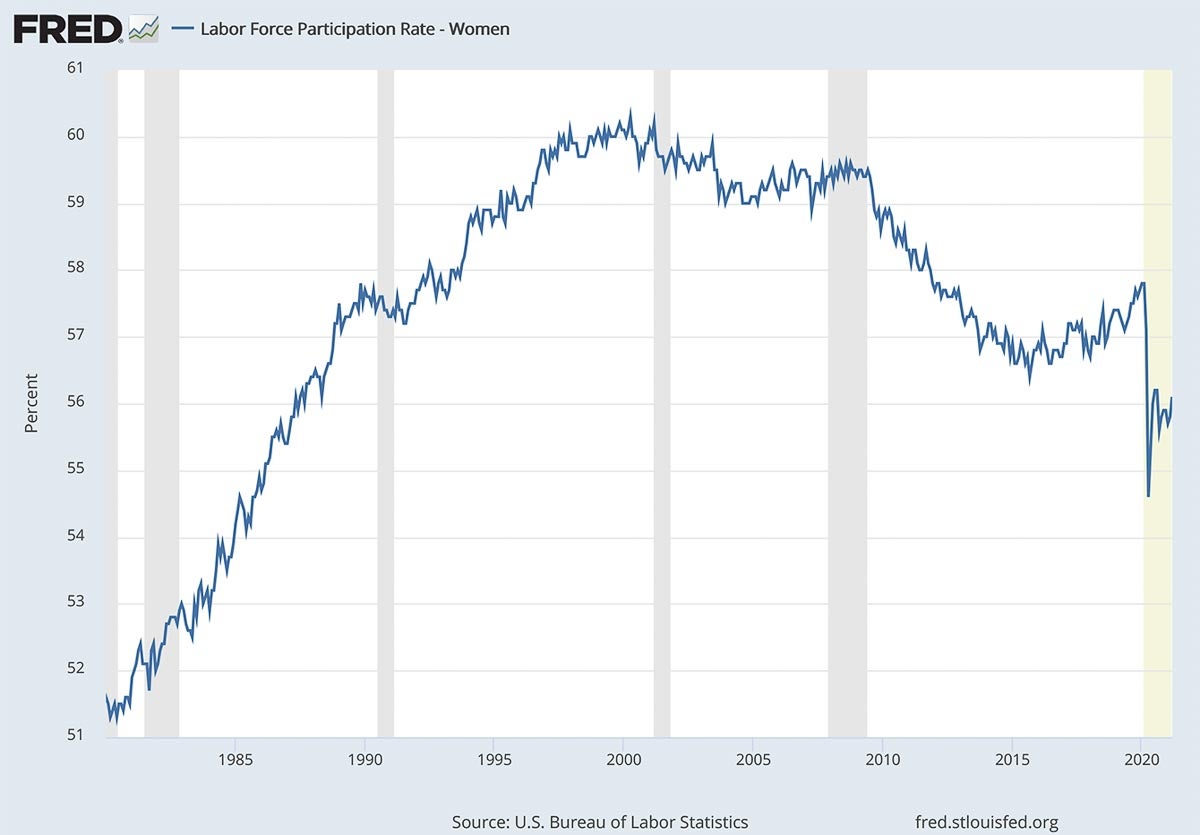

As of March 2021, more than 1.8 million women have left the workforce since the pandemic started. While this number is an improvement over the initial 4.2 million women who dropped out of the job market last April, so many women have left the labor force that the current participation rate has fallen to 56.1%, a level not seen since the late 1980s.

As part of the Urban Edge’s ongoing “COVID-19 and Cities” series, the Kinder Institute for Urban Research is examining the urban landscape a year after the pandemic began. These stories take a look back at the past year and ahead to what will be different in the years to come.

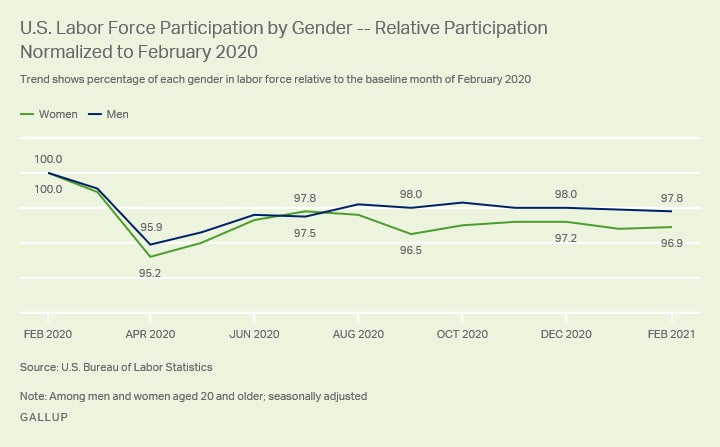

Compared to men, women initially left the workforce in disproportionately higher numbers and their return to the job market has been slower. The graph below shows that using February 2020 as a baseline for both sexes, women have lagged men in their ability to regain their pre-pandemic employment levels. This disproportionate collapse in women’s labor participation has led some to call this the first “she-session.”

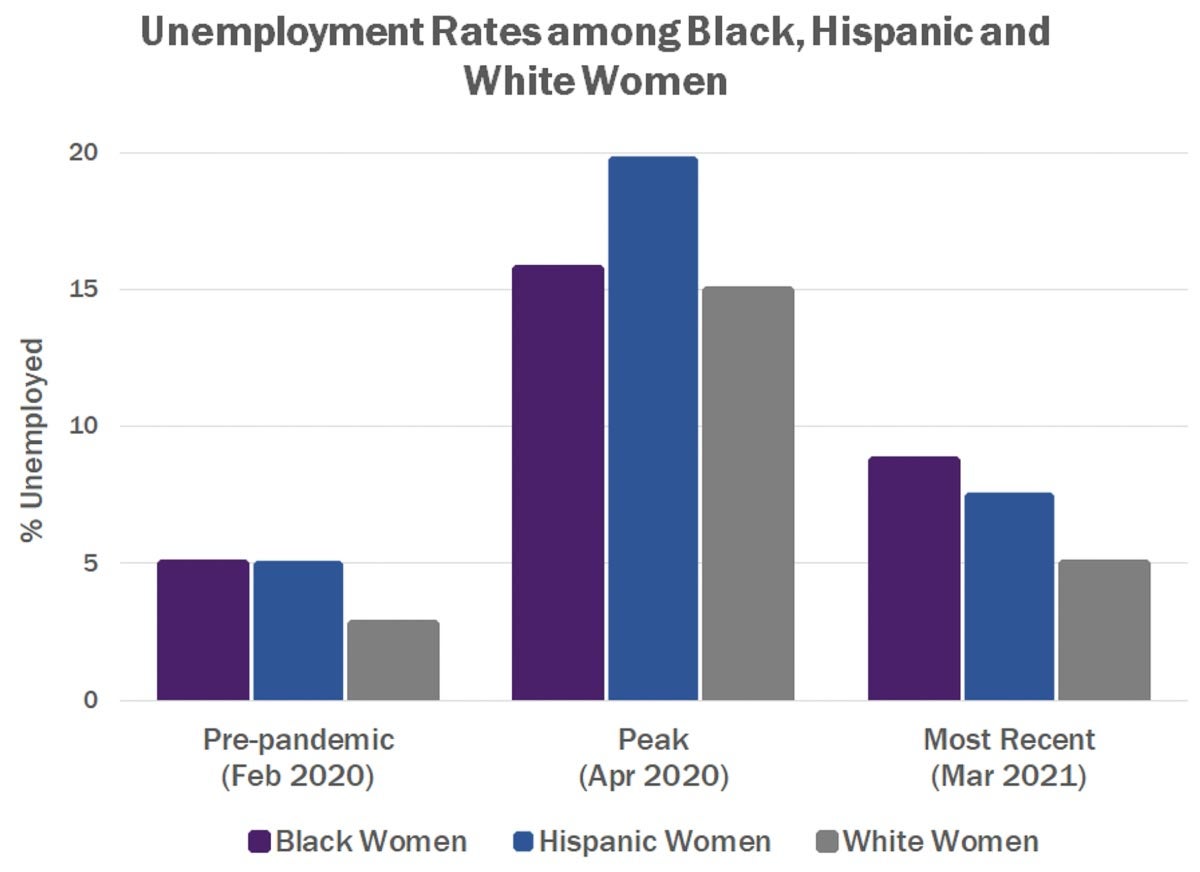

Like everything related to COVID-19, the effects of the pandemic on working women varied among different groups. On average, women of color experienced greater hardships than all other workers, including white women. Comparing the experiences of Black, Hispanic and white women, Hispanic women had the highest unemployment rate — 19.8% — in April 2020, at the peak of the crisis. However, since then, Black women have found their recovery to be slower than the other groups.

Working mothers of young children also have been hit especially hard. As day cares closed and school became virtual, mothers found themselves taking on an even greater share of domestic responsibilities. According to a McKinsey report, 23% of working women with kids under the age of 10 have considered leaving the workforce altogether.

While there is some evidence that women are beginning to find their way back into the labor force, it is important to realize that, like many other inequities the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted in our society, it didn’t create this problem. It simply magnified it. The truth is that growth in women’s labor force participation has stalled since the early 2000s. It began to decline after the Great Recession, mimicking trends in men’s participation rate. Interestingly, this phenomenon isn’t replicated in other advanced economies around the world.

Societal expectations

Even before COVID-19, women performed an unequal share of the domestic responsibilities. In 2018, 9.6 million females gave this as their reason for not participating in the labor force, compared to just 1 million men. This is hardly surprising. When families start looking at the high costs of child care and the lower wages of women, it seems to make the most economic sense. But these individual “forgone” conclusions are predicated on structural failures.

Gender pay gap

Equal Pay Day for 2021 was March 24. This date symbolized how much longer a woman would need to work to earn the same amount men did in 2020. Unfortunately, for Black women, that symbolic day would be in August, and not until October for Hispanic women. We see these inequities at both the national and local levels. In 2017, Harris County had a gender pay gap of $7,500.

According to a study by the National Women’s Law Center, a woman starting her career today stands to lose $406,280 over a 40-year period. Sadly, this earning gap spans all jobs, no matter what career a woman choses. The same study found the gender wage gap in 98% of occupations. As Megan Rapinoe, the U.S. Women’s Soccer star, said in her testimony on Capitol Hill: “One cannot simply outperform inequality.” It is a truly pervasive problem, but it is hardly a new one. In fact, in 25 years, the gender pay gap has only shrunk 8 cents. At this rate, we can hope to close the gap by 2059. While this isn’t a problem exclusive to the U.S., other countries have made much better progress toward ending it.

Besides being paid less for the same work, women are also overrepresented in jobs with lower wages. While there are many underlying causes for this, one of the largest contributors is discrimination. According to a report from the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, occupations with more men tend to pay better regardless of skill or education level. These trends are especially more pronounced for women of color. The implication for this being that even working full time, these women face higher rates of poverty. The negative effects extend beyond women and hurt the next generation. According to a study from the Pew Research Center, single mothers are almost twice as likely as single fathers to be living below the poverty line.

Corporate culture

Even when women enter the corporate world, they rarely achieve success at the same rate as their male counterparts. In 2013, Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg’s bestselling book "Lean-In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead" became a cultural phenomenon. The can-do manifesto centered around the idea that women were holding themselves back in their careers, and with enough hard work, they could thrive both at home and in the office. But in a few short years, even Michelle Obama was publicly denouncing the idea. It’s become clear that what is holding women back is not their lack of effort. Corporate culture’s lack of support and flexibility, combined with its shift to longer and longer hours, has forced many women to realize their only option is to opt-out.

Reversing the COVID-19 damage and helping women succeed

Our ability to recover from the current economic crisis depends on women re-entering the workforce. Our ability to find new levels of economic growth depends on women being able to find economic success equal to men. Luckily, there is considerable overlap in the kind of policies needed to achieve both goals.

The pay gap is a fundamental problem women faced before the pandemic, and one they’ll continue to face when it’s over. The Paycheck Fairness Act that has been introduced in both the House and the Senate works to eliminate pay discrimination at the federal level. Given the current makeup of Congress, there is a chance it will pass. However, the bill was first introduced almost 25 years ago, in 1997. We have seen minimal gains in pay equity in the past quarter-century, and it is beyond time to make this law a reality. Other ways to close the gap include helping women achieve entry into the higher-paying, male-dominated fields, and raising the minimum wage, as women have an outsized representation in lower-paying jobs.

Another roadblock for women is America’s embarrassing lack of maternity leave. As other countries continue to see its benefits, and even begin to expand into paternal-leave policies, the lack of support for women and families in the U.S. becomes even more glaring. Interestingly, while the federal government continues to ignore this critical issue for all workers, it recently expanded paternal benefits to federal employees. Many state and local governments are also trying to fill in the holes as well. In 2013, Austin became the first city in Texas to offer paid paternal leave for workers. It even launched a toolkit in partnership with Early Matters Greater Austin to help businesses see the benefits of such policies. Since then, San Antonio, Fort Worth and smaller cities like Lake Jackson and DeSoto have joined Austin in extending this benefit to employees. DeSoto even included the employees in its police and fire departments.

Oftentimes for women, the problem of finding affordable child care becomes almost insurmountable. In Texas, child care often costs more than college tuition, and parents don’t have 18 years to save for it. Even before the pandemic, child care in Texas was facing a tipping point. At one time, the U.S. had a national child care program. During World War II, when many women joined the labor force to help with the war effort, the U.S. implemented a far-reaching and heavily subsidized child care program. Under that program, child care cost families $7 a day in today’s dollars. Any parent with kids in day care will find this amount shockingly small compared to their most recent bill.

While there are many ways to fix the current system, it all boils down to one thing — money. Public investment is critical. Nowhere in the world is affordable child care achieved without government funds. While the price is high, it is estimated that U.S. businesses lose roughly $4.4 billion a year because of lost productivity due gaps in child care. The current child care system is a drag on our economic prosperity and an impediment to gender equality. Change, while not cheap, is necessary.

Flexibility in the office has the potential to improve the lives of all workers — not just women. The backlash to corporations’ focus on “presenteeism” has been around for years. COVID-19 has shown that there are many jobs that can be done remotely or on a flexible schedule. Even Goldman Sachs has started to see pushback against work’s greedy demands on workers’ time.

Time to act

COVID-19 has shown that, for all the advancements women have made in the workforce, the main impediment to gender equality is the structural barriers they face. COVID-19 further loosened the tenuous grip that kept many women in the workforce. A lack of support from both businesses and the government continues to hinder women’s ability to reach their full economic potential, and by extension, the U.S. economy’s. A study often cited by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen estimates that “increasing the female participation rate to that of men would raise our gross domestic product by 5 percent.”

As Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell pointed out in his recent Congressional testimony: “Our peers, our competitors, advanced economy democracies, have a more built-up function for child care, and they wind up having substantially higher labor force participation for women. We used to lead the world in female labor force participation, a quarter-century ago, and we no longer do. It may just be that those policies have put us behind.”

To support women and encourage their return to the workforce, we need to follow through on policy proposals that have been around for decades yet still remain unimplemented. We have seen their benefit in other parts of the world and, if we don’t want the economic fallout of COVID-19 to become permanent, now is the time to act. Our collective prosperity depends on it.