As the Houston Independent School District welcomes a new superintendent, what can we do to support him and the roughly 200,000 students in the district? And how should districts spend millions in COVID relief funds? I’ve got a few ideas, gleaned from what we’ve learned over the past decade at the Houston Education Research Consortium, at the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, at Rice University.

I’ve arrived at the conclusion that the most important thing we can do to help students in HISD, and the rest of our region, is to ensure that educational resources are distributed equitably — meaning that those who need more, get more.

Unfortunately, many of our systems are set up to do the opposite. In HISD, as well as the nation, Black and Hispanic students are five times more likely than white students to attend a high-poverty school, in which 75 percent or more students are in poverty. Although there are wonderful examples of high-poverty schools whose students beat the odds, research shows that these are rare and challenging to sustain. Even though it’s true the district alots roughly the same amount of money per student, and often more for low-income students, concentrating poverty in schools still leads to fewer resources. Most high-poverty schools struggle to recruit and retain effective teachers and administrators. They generate lower test scores, utilize more disciplinary action and offer fewer advanced courses. Most importantly, the racial concentration of poverty in schools is the strongest predictor of racial achievement gaps, according to the Educational Opportunity Project at Stanford, based on 10 years of data from over 4,000 school districts and about 430 million test scores.

As a result of concentrated poverty, in HISD, Black and Hispanic students’ test performance is equivalent to 3.0 and 3.6 academic years below white students, as if they were absent for a quarter of their K-12 schooling. Pause here, reread the previous sentence, and let that sink in for a moment.

This problem is compounded by the fact that Blacks and Hispanics make up two-thirds of Texas’ public student population and 84 percent of HISD’s. Students bearing the brunt of our inequitable systems are no minority — they are the largest and fastest-growing group.

Bleak as it may seem, the challenge can be overcome, just not by tinkering at the edges, and not with magical thinking about quick fixes. It will take understanding our history and using the tools that concentrated poverty in the first place to rebuild differently after the pandemic.

Closing academic performance gaps requires a systemic approach — one that moves beyond individual actions, such as how hard students work, how well teachers teach or how much parents care about their children’s education. These factors definitely matter, but they don’t explain academic performance gaps between groups.

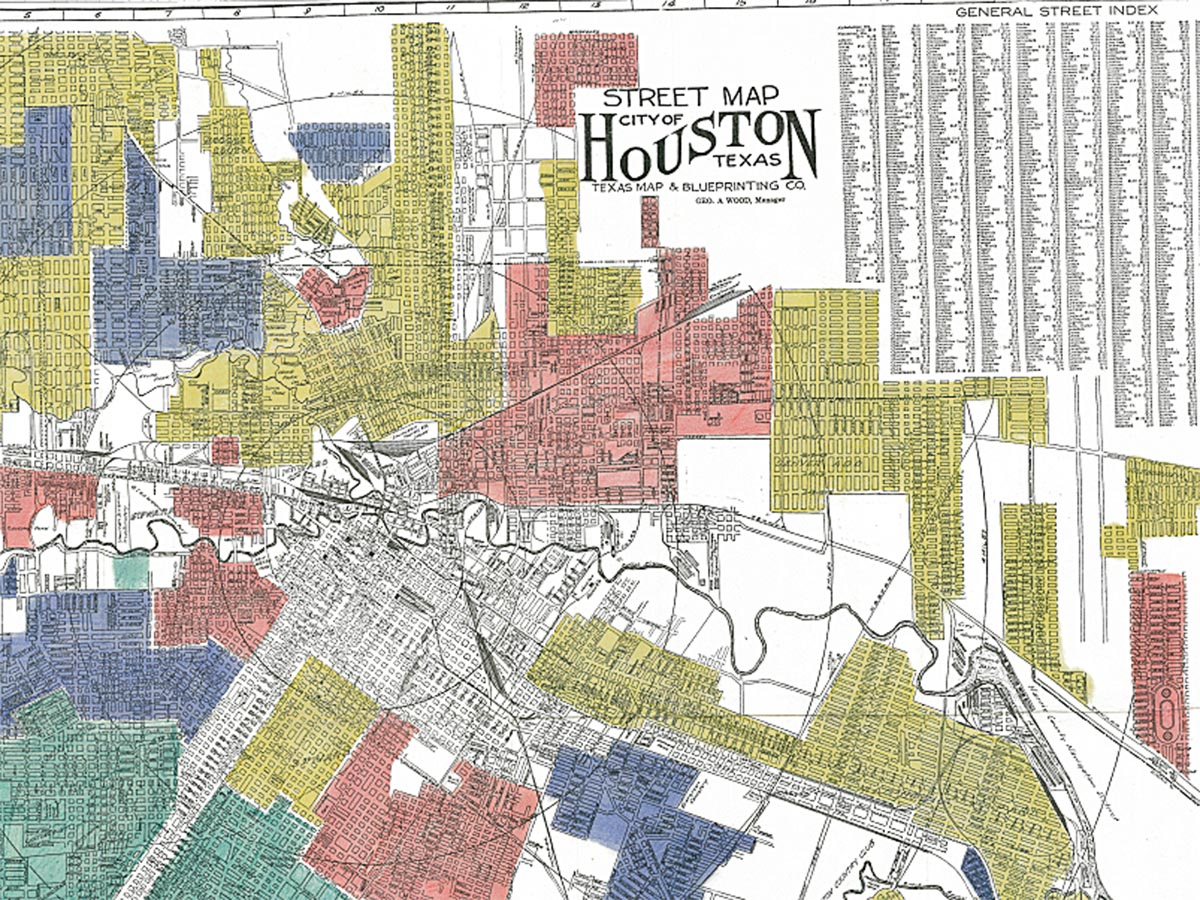

A systemic approach begins by acknowledging our region’s history. Most of the educational inequities described here did not develop by chance but by careful planning by our predecessors. Historian Karen Benjamin documented that, during a massive school expansion program in 1924, the newly created HISD school board worked closely with the city’s planning commission to develop a racialized zoning system in order to protect real estate interests. This powerful coalition determined where 50 new school buildings would be located. The “redlining” map of Houston made by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation reveals how deliberate and pervasive this type of planning was.

Although schools were already segregated by race, Black schools and white schools previously were located in the same neighborhoods, with one Black school in each of Houston’s six wards. However, during this expansion, new school sites were selected to create segregated neighborhoods, and schools that did not fit the master plan of racialized zoning were closed, neglected or moved. Wheatley High School opened in Fifth Ward during this era in 1927. A new school officially designated “Mexican School” (later renamed De Zavala) was built in Magnolia Park and cost $135 per student, compared with the least expensive white school, which cost $250 per student.

In 1929, a Texas appellate court declared this unconstitutional and the City Council rejected the commission’s zoning plan, but school construction was almost complete and the damage was done, setting in motion a powerful system that persists almost 100 years later.

What does a systemic solution entail?

Undoing that legacy requires a systemic approach coordinated at the local, state and federal levels. At the local level, districts can begin with efforts to reduce the concentration of poverty in schools and improve the distribution of resources. Improved implementation of magnet programs and controlled-choice programs can help with economic integration, and school zone boundaries can be adjusted within a district to reduce segregation.

Zooming out, coordination among different school districts is more complicated and may take longer to achieve, but our research can help inform these efforts. For example, we have studied regional student mobility patterns and discovered that when students move to a different school, 70 percent of mobility occurs within one of six geographic areas that intersect school district boundaries. We can also identify which students are likely to move, as previously mobile students are three times more likely to move than others. Inter-district agreements, such as data sharing and curricular alignment, or letting a child stay at a school even after they have moved to a different zone, can help reduce the disruptive effects of mobility. Student mobility patterns can even be used to inform efforts to integrate students over time across the region. Using the pandemic aid to set up some of these systems within and across districts will help now and keep going after the aid is spent.

At the federal level, efforts are already underway to promote school integration, including the Strength in Diversity Act, the Economic Fair Housing Act and changes in Title I funding. At the state level, more can be done to increase funding for our most disadvantaged students (and more equitably distribute that funding), to improve how the state measures gaps, and perhaps even to introduce accountability for integration. Texas also needs to apply lessons learned from its “Robinhood” program of redistributing resources.

These academic achievement gaps are even more costly in the long run. Nationally, the gaps, which average two to three years of schooling, greatly hinder economic growth and suppress earnings and tax revenue. A 2009 report by McKinsey & Company estimated that gaps in U.S. educational achievement had affected GDP more severely than all recessions since the 1970s. More recent estimates from the Center for American Progress suggest that closing gaps would increase GDP by $551 billion and increase local, state and federal tax revenues by $198 billion annually. These returns are worth the investment to close gaps.

We have known about this crisis for years, and it may seem intractable. Hasn’t each new superintendent announced a bold plan to boost underperforming schools? Weren’t pay bonuses for effective teachers supposed to make all the difference? Some findings from our 10 years of research are encouraging, others discouraging, but all of it is informative and consistently points to the need for more equitable systems. It’s not that prior efforts were completely wrong. They just lacked plans to rethink the distribution of school resources, within school districts and beyond. Through the Equity Project, HISD has begun to examine the distribution of resources such as academic and extracurricular programming, student supports, technology and facilities.

As we plan for the next 10 years, I believe we are at an opportune moment, because of what we have learned and even because of the pandemic. While the pandemic made our challenges worse, especially for students who were already struggling, it has done two things that give me hope: It has raised awareness of inequities and their consequences, and it is bringing an estimated $800 million in stimulus funds to HISD and an estimated $18 billion to Texas. The Biden administration has also included $20 billion in its proposed budget to even out disparities.

If we want to undo the racialized system we inherited from our predecessors, we must recreate a coalition of cross-sector leaders and community stakeholders from all racial groups and neighborhoods to dismantle the system of racialized zoning that continues to harm our students, our economy and our democracy. The work of the coalition should be grounded in local data and research, and incorporate the voices of those with differing perspectives.

We know systemic approaches are effective and powerful because the one we inherited achieved its goals and has lasted nearly 100 years. Houston is ready to dismantle concentrated poverty in our schools and close the academic performance gaps that have plagued us far too long. Any efforts on the part of HISD and all our region’s districts will require extensive support from the entire community. I can’t think of a better way to welcome the new HISD superintendent.

This post was previously published by the Houston Chronicle and was based on an earlier version published by Understanding Houston.