Texas has a reputation as an affordable place to live — largely because the cost of housing is much less than on the coasts. But the truth of the matter is that housing in Texas is gradually becoming less affordable — especially in the large metropolitan areas where virtually all of the population and economic growth is taking place. And that trend could prove to be a brake on Texas’ economic growth down the road. The current coronavirus pandemic will only further complicate the situation.

Indeed, even Gov. Greg Abbott — speaking in San Antonio in January — said that although people have been fleeing the coastal states for Texas because of housing affordability, “that affordability issue is now beginning to bite Texas.”

This post is part of our “COVID-19 and Cities” series, which features experts’ views on the global pandemic and its impact on our lives.

This problem will only get worse with the COVID-19 crisis — not because home prices are rising (they’ll probably fall), but because so many people will lose income and may not be able to make their rent or mortgage payment.

With that in mind, here’s an overview — mostly pre-COVID — of housing affordability trends in Texas. (Most of the data in this report is drawn from the State of the Nation’s Housing 2019 report from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University.)

State’s housing problem is concentrated in the Triangle

Like so many issues in the state, Texas’ emerging affordable housing problem is concentrated in our large metropolitan areas — and in particular, the so-called “Texas Triangle” (the 35 counties surrounding Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin and San Antonio). Some 18 million of Texas’ 29 million residents live in the Triangle and, as the chart below shows, 85% of new population growth since 2010 has been in the Triangle.

In addition, almost 80% of the state’s economy takes place in the Triangle. Essentially, all of Texas’ economic growth — with the exception of the Permian Basin — occurs in the Triangle’s metropolitan areas.

For this reason, this overview focuses mostly on large metros in Texas (including, in some cases, El Paso, Midland and a few others outside the Triangle).

Rate of homeownership in large metros lags behind the nation

As the figure below shows, the median home price remains reasonable in most of Texas’ large cities.

In particular, the median home price in Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio and Houston remains in the vicinity of $200,000. Median home price has increased very quickly in Austin and was approaching $400,000 in 2019, making it more of a “coastal city” — at least in terms of real estate — than other Texas cities. Midland also saw a rapid rise in home prices because of the booming energy sector.

With COVID-19 slowing the economy, it seems likely that home prices will drop. Given the energy bust, the decline in Midland is likely to be even greater.

At the same time, however, homeownership rates in large Texas metros fall below the national average.

The national homeownership rate is 64% — that is, 64% of all households live in homes owned by the occupants. The rate in Texas is 62%. With the exception of San Antonio, which has a homeownership rate of 63.3%, large metropolitan areas in Texas have a rate of homeownership measurably lower than the national average. As homeowners who have lost income because of COVID-19 struggle to make their mortgage payments, it is a virtual certainty the homeownership rate will go down.

Austin’s homeownership rate is 57.7% — more than six points below the national rate and four points below the state rate. This isn’t surprising given the fact Austin’s median home price is close to double that of the state’s other major cities.

However, both the Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan areas also have measurably lower homeownership rates than the state and the nation as a whole. Houston’s homeownership rate is 60.7%, in Dallas-Fort Worth the rate has dropped below 60% — down to 59.7%

In other words, in Houston and especially D-FW — despite the overall affordability of the housing stock — the homeownership rate is closer to that of Austin than to the national average.

Why is this happening?

One possible reason is that Texas’ property taxes are very high compared to other states. Texas has a reputation as a low-tax state, primarily because it does not have a state income tax. But, according to WalletHub, the state’s effective property tax rate is 1.81% — ranking it 45th in the nation, below states such as New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Michigan and far below California.

Although property tax is not part of a home’s price, it is part of the cost of home ownership and often is built into the homeowner’s monthly payment. For a $200,000 house, an effective tax rate of 1.81% means the owner pays $3,600 a year or $300 per month in property taxes. A typical homebuyer might put 20% down ($40,000) and make a mortgage payment of approximately $1,400 per month with a 4% interest rate.

The rising ratio of home price to income

Another possibility is that the ratio of housing price to income in large Texas metropolitan areas is going up.

The ability to purchase a home is not solely dependent on housing price. It also depends on the household’s income and, in particular, the ratio of housing price to income. Traditionally, the rule of thumb was that there should be a 3:1 ratio between home price and income. For example, if a home costs $210,000, the household should have an income of $70,000. This rule of thumb has been stretched in recent years as home prices have gone up and interest rates have come down.

Nationally, as the chart below shows, the ratio of housing price to income has risen from 3.5 to 4.0 in the past decade. Not surprisingly, this ratio has gone up at about the same rate in the Austin metro, where home prices are the highest in the state.

Of greater concern, however, is the fact that the ratio of housing price to income has gone up considerably in the San Antonio, Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston metros in the past decade. Despite low housing prices, for example, San Antonio’s ratio in 2018 was 3.88. This is probably because San Antonio generally has low incomes compared to the other large Texas metros. According to the U.S. Census, of the 25 largest U.S. metros, San Antonio ranks 23rd in median income, ahead of only Miami and Tampa, Florida.

But this trend has also been pronounced in Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston, two metropolitan areas that do not have unusually low incomes and together account for almost half of the state’s population.

In 2009, both metropolitan areas had extremely low ratios of housing price to income — 2.59 in D-FW and 2.71 in Houston — compared to the national average of 3.44. However, over the following 10 years, most of that difference was eliminated. By 2018, D-FW’s ratio (3.67) was higher than Houston’s (3.58), and had grown faster than the national average.

If this trend continues, the housing price advantage of the two largest metropolitan areas in Texas will be completely erased in the next few years.

And there is every reason to believe this gap will continue to narrow. That’s because raw land prices for single-family homes continue to increase in Texas’ large metropolitan areas.

According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard, in the five-year period between 2012 and 2017, the price of raw land for single-family homes increased 68% in metropolitan Austin, 38% in metropolitan Houston and 22% in metropolitan Dallas-Fort Worth.

But, as more detailed statistics from D-FW show in the chart below, land prices are going up faster in close-in counties. Prices went up 34% in Dallas County and 61% in Collin County, the fastest-growing large county in the state.

Renters are cost-burdened and their options are dwindling

Texans are more likely to be renters than others nationally, and renters are more likely to have modest incomes and work at low-wage jobs. Oftentimes, service workers cannot afford to buy a house even at Texas prices. Like homeowners, however, renters are feeling the pressure of rising cost relative to incomes.

For example, half of all renters are cost-burdened in all Texas markets. A rule of thumb, especially for renters, is that a household should spend no more than 30% of its income on housing. Households that pay more are said to be “cost-burdened”. As the chart below shows, for homeowners in most Texas markets, about 25% are cost-burdened. But for renters, that figure is doubled — close to 50% in most markets. This figure is high not only in D-FW and Houston, but also in Rio Grande Valley cities such as Brownsville and McAllen, where incomes are low.

Furthermore, even as half of all renters in Texas metropolitan areas are cost-burdened, the amount of low-cost rental housing ($800 a month or less) is declining fast, as the chart below shows.

Astoundingly, Austin lost two-thirds of its low-cost rental housing in the five years between 2012 and 2017. But the low-cost rental housing stock is declining fast in Houston (33%) and, especially, D-FW (40%), reinforcing the idea that these metros are gradually losing their affordability advantage.

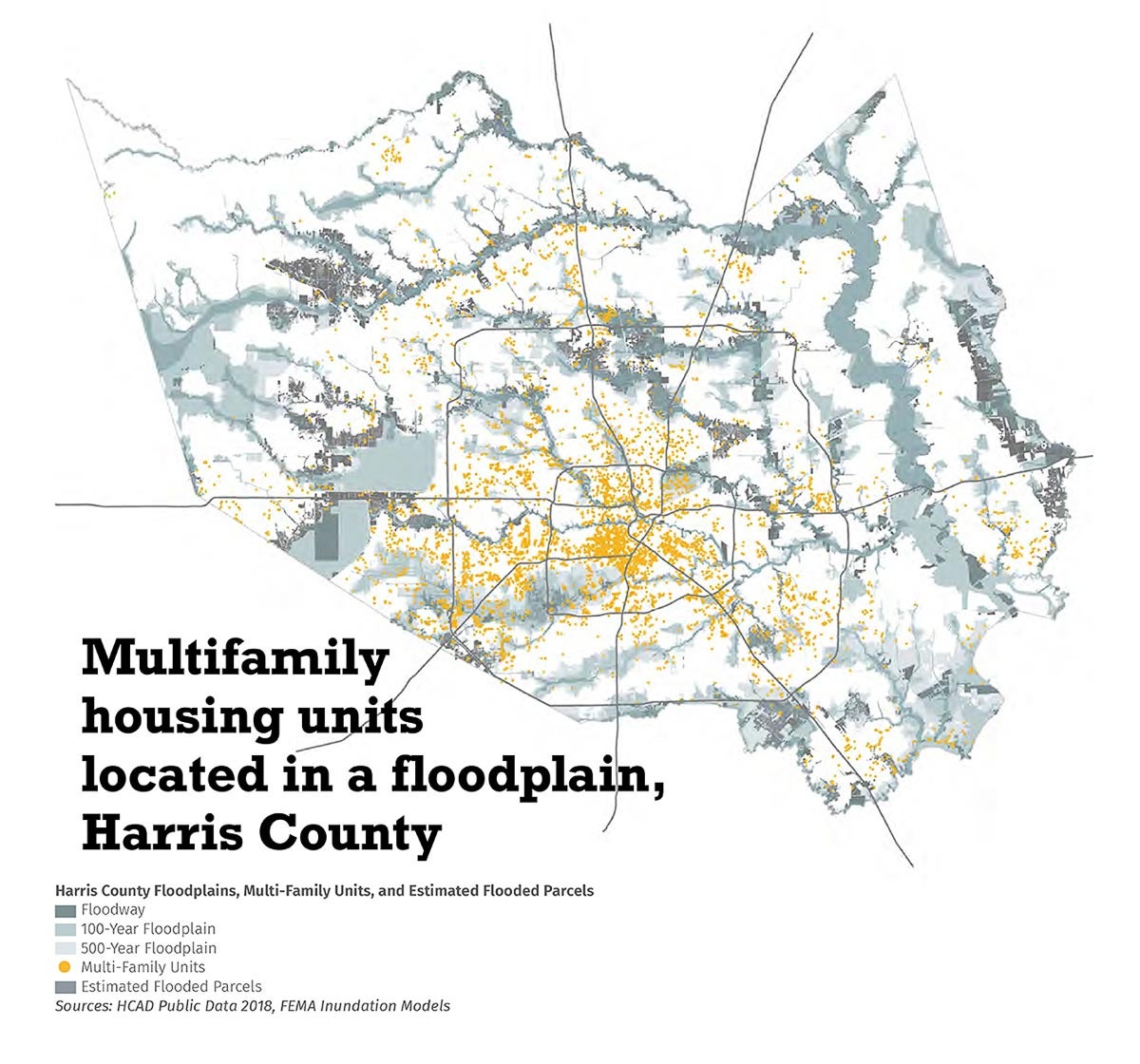

In addition, affordable rental units are often located in risky areas. A recent analysis by the Kinder institute and several research partners concluded that 165,000 multifamily units in Harris County — about one-quarter of the total — are located in the floodplain.

Source: Greater Houston Flood Mitigation Consortium

Differing views on what to do from the right and left

There is no question that Texas’s large metropolitan areas — where most of the state’s population lives and where virtually all of the population growth is occurring — are gradually losing their housing affordability advantage, which has been one of the most important factors driving the state’s population growth in recent years. This advantage has virtually disappeared in metro Austin and is quickly eroding in metro D-FW and metro Houston.

People on the political left and right view the problem differently and favor different solutions — though conservatives focus on homeowners while liberal focus on renters.

For conservatives, the most important policy issue has been property taxes, which is why they view the property tax reform passed by the state legislature last year — limiting increases in property tax revenue to 3.5% unless there is a vote — is so important. Other than property taxes, conservatives in Texas tend to focus on limiting regulation and maintaining a large land supply as necessary policies to keep the cost of market-rate housing down, thus allowing the private market to serve as many people as possible.

Having virtually halted the real estate market for the moment, the COVID-19 crisis will almost certainly drive down the cost of both raw land and market-rate housing. However, when prices go down, developers often cannot make their projects “pencil out” — and the result is less housing construction, not more.

For liberals, the prevailing view is that the private market cannot and will not serve all residents, especially renters. Therefore, they often advocate for significant government interventions similar to those used in the “blue” states and metros on the coasts. However, many of these interventions — such as inclusionary zoning (requiring a certain percentage of housing units in a market-rate project to be set aside as affordable) — are not permitted in Texas.

For these reasons, it will be difficult for Texas to reach a consensus on how to approach this emerging problem of housing affordability. Of course, an effective policy may be different in different contexts. Solutions may be different for homeowners, who need affordability that the market can provide, and renters, who need affordability that the market may overlook. Solutions may also be different in large cities, small towns and suburbs in Texas’ metropolitan areas, where political circumstance and financial capacity may differ.

But one thing is for sure: The problem emerging is a big one — it affects Texas’ ability to attract residents in a very direct way — and COVID-19 will make the problem worse by putting both homeowners and renters at risk.

This blog post is based on a presentation to the recent BBVA Regional Partners Conference in Houston.