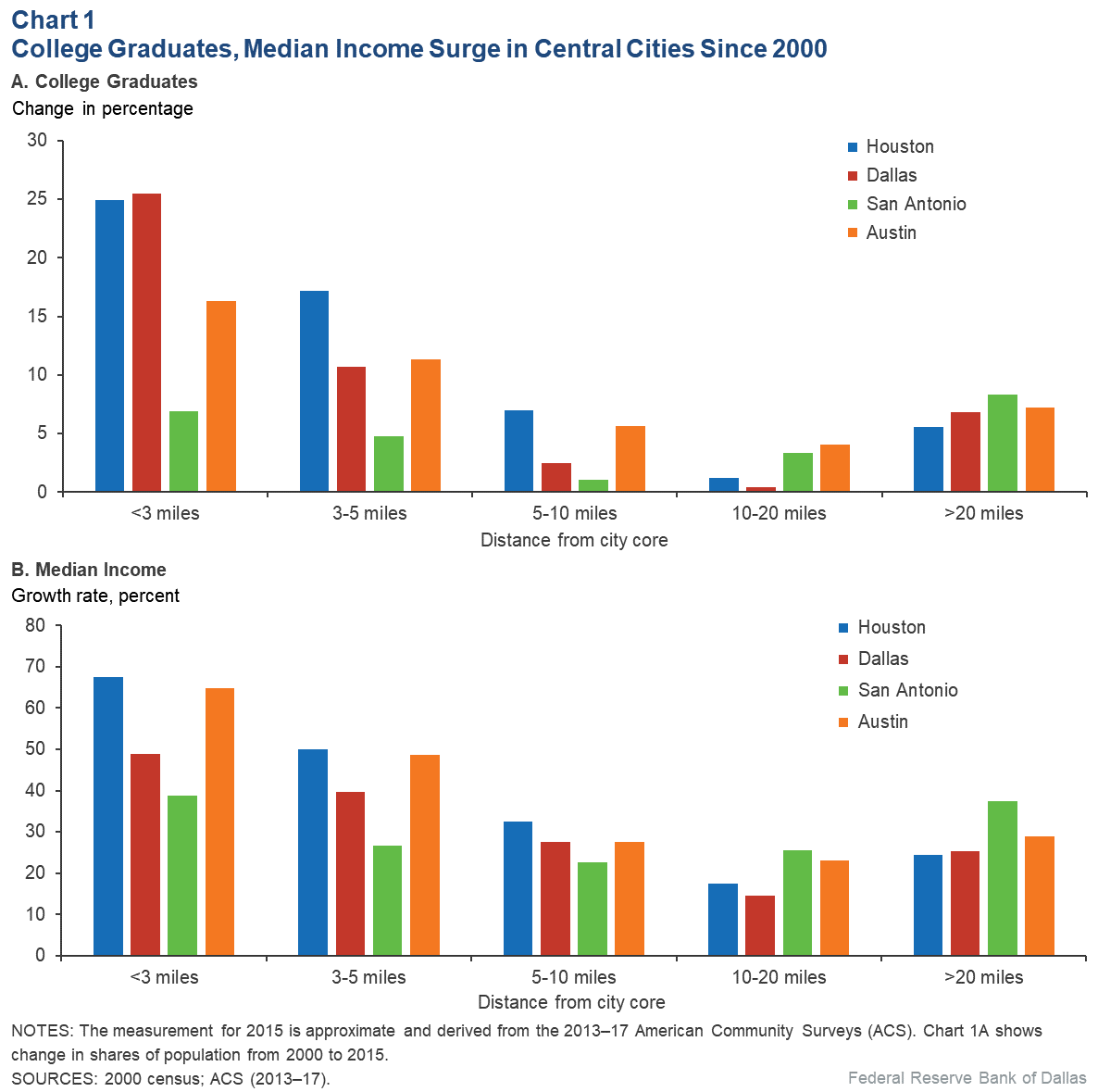

And Houston is gentrifying more quickly than the other Texas cities, according to a Federal Reserve Bank in Dallas analysis of American Community Survey data from 2013-2017. From 2000 to 2015, the median income in areas less than 3 miles from downtown went up by 67%. By comparison, median incomes in areas near the centers of Dallas, San Antonio and Austin increased by 49%, 39% and 65%, respectively.

The rate of median income growth in Houston slowed progressively in areas farther from downtown, from 50% in those 3-5 miles away to 32% in areas 5-10 miles out to an increase of 18% in neighborhoods 10-20 miles from the city’s center. The rate increased again, to 25%, for those living more than 20 miles from downtown.

The number of college graduates living less than 3 miles from the center of Houston increased by 25% between 2000 and 2015. The median income in those areas went up by almost 70%. At that same time, there were 17% more college graduates living 3-5 miles from the center; and median income increased by more than 50%.

As higher-income residents have moved into predominantly lower-income areas closer to the cities’ centers, changes in available housing and home values inevitably have followed. In past generations, this demographic — higher-income college graduates — would have chosen to live in suburban areas farther urban communities perceived to be low-income and high-crime.

But what are the consequences of these transformations? Has the flow — a steady trickle in some parts of Houston, an open fire hydrant in others — swept some existing residents out to the suburbs?

Though it seems likely, there’s not a definitive answer. That’s because of “insufficient detailed data on the migration history of individuals,” says Yichen Su, a research economist and author of the report. According to Su’s analysis, the influx of high-income residents who are college graduates into the cities’ central areas can lead to improved amenities but also higher housing costs that make living there unaffordable for low-income (those making less than $30,000 a year) and at-risk populations.

“High skilled or college-educated workers like certain amenities in the city, so when they go into a nice downtown neighborhood, they transform the amenities there,” Su told the Houston Chronicle. “Things like Whole Foods and Starbucks come in, and those things become attractive to other ‘gentrifiers,’ and that increases the demand for housing.”

Displacement and the pros and cons of gentrification

Some argue gentrification brings investment, revitalization and renewal to neighborhoods, and helps increase the diversity, both racially and financially, of an area’s population. On the flip side, if gentrification occurs quickly, existing — often long-term — residents may be priced out of areas by higher rent costs and property values. In addition to removing affordable housing options, it often damages a neighborhood’s cultural traditions and destroys deep-rooted social networks and longstanding amenities.

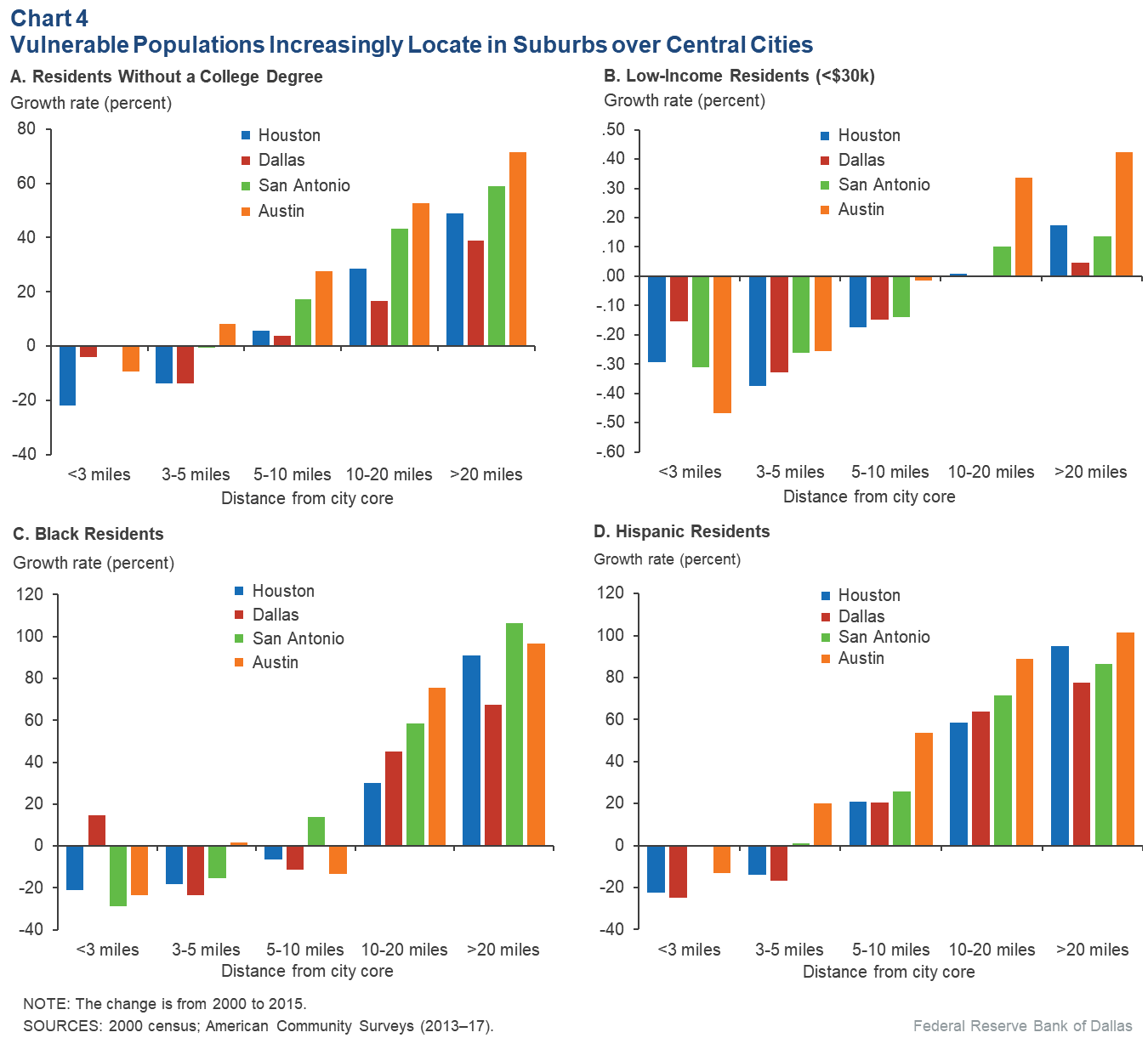

While it’s important to note that gentrification doesn’t automatically result in displacement, the Federal Reserve report indicates that low-income and vulnerable populations have decreased in central cities and increased dramatically in suburbs, as this chart illustrates:

Gentrification in the Houston area

Researchers with the Kinder Institute for Urban Research who studied gentrification in Houston between 1990 and 2016 found it rarely occurred in the last decade of the 20th century before taking off, beginning in 2000. The greatest increase occurred in the first decade of the 21st century but continued to rise between 2010 and 2016 with growing gentrification patterns emerging during that time. Gentrification affects many of the city’s neighborhoods, both inside and outside the 610 loop.

They found that as neighborhoods change, some households benefit from “considerable transformations in the social and built environment while disadvantaged households are economically challenged by rising housing costs caused by the in-migration of more affluent households and facing pressures of unwanted neighborhood changes.”

Experts say the damage done by gentrification could be mitigated by the equitable revitalization of neighborhoods, which would provide “housing preservation, new mixed-income housing and even employment opportunities that benefit existing residents.”

What can be done to battle displacement?

It’s important to keep gentrifying neighborhoods diverse and inclusive, but how? To enable existing residents who are low-income homeowners and renters to remain in these areas, there have to be affordable housing options.

As the Federal Reserve report points out, there’s general agreement among urban researchers and economists that increasing the supply of housing in gentrified areas is an effective way to combat rising housing costs and housing stock shortages. However, that may be easier said than done.

Public housing, housing choice voucher programs and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) can offer tools to preserve housing affordability.

Without zoning, communities in Houston have employed local land-use tools such as minimum lot size protections, minimum building lines and Chapter 42 — the city’s land development ordinance — to stop developers from subdividing plats and replacing old homes with townhomes. Other strategies to curb the unwelcome changes brought by gentrification are deed restrictions, homestead exemptions to help limit property tax increases, and community land trusts.