As Charlotte continues its quest to become a more urban and cosmopolitan city, is it possible that the small towns and former mill villages dotting the land around Charlotte have something to teach us about how to solve some of the biggest and most pressing needs facing our big cities and suburbs today?

Bill Fulton, Director of the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University, recently published an essay reflecting on how his hometown of Auburn, New York, had shaped his understanding of urban planning and policy. It was in part a story of a small town’s decline as a prosperous manufacturing and retail center, and the well-intended but misguided attempts of local officials to reverse its economic slide.

But as one of the country’s leading advocates for urbanism, Fulton likely surprised some readers by crediting Auburn — some 20 miles from even a mid-sized city like Syracuse — for having taught him some of his most valuable lessons about what it takes to create and sustain great urban places. And that got me to thinking about how my own upbringing near a small industrial town east of Charlotte unexpectedly shaped my views about some of the big planning issues facing Charlotte today.

The place where I grew up was actually a rural valley of small farms adjacent to Morrow Mountain State Park, about equal distance between the towns of Albemarle (population 16,100) and Badin (population 1,969). Like Auburn, both were what Fulton would call “factory towns” — Albemarle built on textiles and Badin on aluminum.

Albemarle was the more conventional of the two, first established as a traditional county seat and market town before the railroads brought the mills that would fuel its expansion in the early 20th century. Its central “square,” two- and three- story commercial buildings, and a classic grid of tree-lined residential streets (later extended to accommodate the “mill villages”) was an urban form typical of textile communities across the Carolinas.

Badin, on the other hand, was something altogether different. Even as a boy, I could tell that there was something unique about the place, despite its daily rhythms and paternalistic customs common to all company towns.

Geography alone was enough to set it apart. Built on the shores of Badin Lake, which had been created at the “Narrows of the Yadkin” to provide hydro power for the aluminum smelting plant, Badin was surrounded by the gentle hills of the Uwharries, creating a picturesque setting with few rivals across the South’s industrial landscape.

Badin’s built environment also suggested something special, which most of us could sense even if we couldn’t explain. Its design seemed more deliberate, even artistic, than the standard formula for southern textile towns.

I recall peering out the class windows of the old Badin Elementary school, with its intricate brickwork and cupola-style belfry, and admiring the row of early 20th-century bungalows across the street, built in the French Colonial style (not that I knew what that was at the time). And after school, I would occasionally walk home with friends to one of the many “quadraplex” apartments, built to house the families of workers in the nearby aluminum plant. Those apartments were strange and alien, in a pleasant way, to a kid more familiar with the single-family, vernacular mill houses common to Albemarle and other nearby towns.

When I would join friends for playdates, we’d ride our bikes on Badin’s winding streets, connected by curious back alleys and lined with open, stone-walled storm drains. These storm drains were spanned by simple concrete footbridges linking homes to sidewalks, lending a quaint European character to the streetscape of this industrial town in rural North Carolina. That was perhaps my first lesson in the old design maxim that “form follows function.”

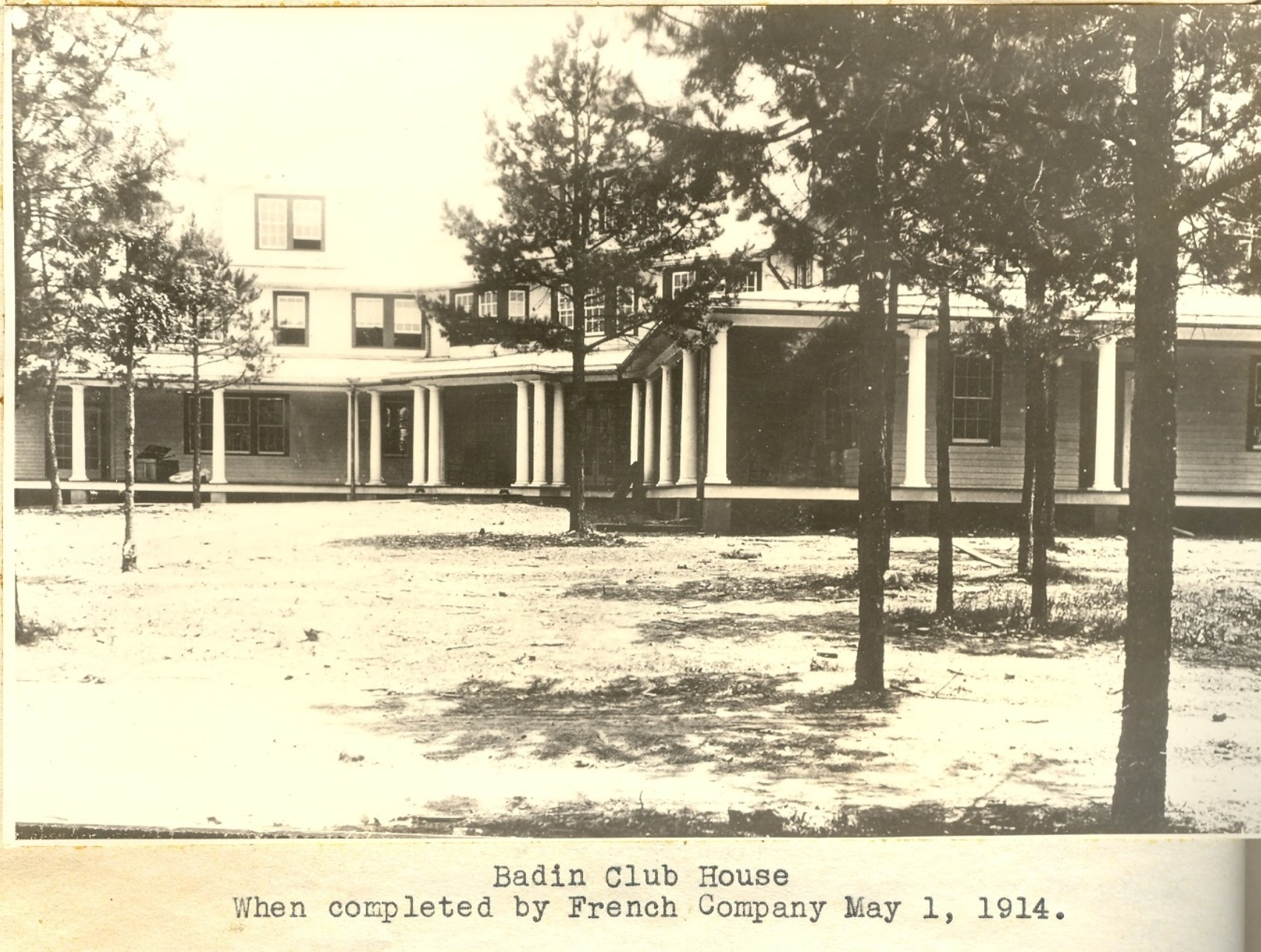

And on a nearby hill, watching over this modest residential neighborhood, was a somewhat incongruous structure that, paradoxically, had the effect of harmonizing the whole — a stately clubhouse in a grove of tall pines, surrounded by an 18-hole golf course that looked as if it might have been transplanted from the village of Pinehurst, some 50 miles east.

It was years before I understood that this strange collection of urban design features wasn’t some happy accident. Badin was in fact a unique planned community, carved from the rugged forests and farmland of eastern Stanly County in the years just prior to the first World War, incorporating many of the progressive ideas that had recently emerged from Europe about using urban design to improve the lives of industrial workers.

I was in graduate school when I first read the report of architectural historians Brent Glass and Pat Dickinson, documenting Badin’s legacy as an early model company town. Initially laid out by a French aluminum company (hence the French Colonial architecture), Badin’s construction was completed by Andrew Mellon after the French sold their interests following the outbreak of war. With this new understanding of the town’s origins, it was then easy to connect the dots between Badin and an important period in the history of urban planning — the Garden City movement.

Suddenly, I saw those familiar quadraplex apartments in a new light, along with the town’s eclectic mix of residential, commercial and industrial uses, with a generous supply of open space and cultural amenities sprinkled throughout. All those features were woven together by a network of curvilinear streets that worked with, rather than against, the contours of the land, recalling Frederick Law Olmstead’s philosophy of organic design. And I was amused by the planners’ clever embrace of the newly imported game of golf to create a facsimile of one of the Garden City movement’s most notable design features — the greenbelt.

Which is not to say that Badin was perfect. Even though its housing and civic structures for African-Americans were lauded at the time for being among the most progressive in the South (Mellon himself came down from Pittsburgh for the dedication of the imposing West Badin School), Badin was still a southern town built in the Jim Crow era, where the races were kept separate and were definitely not treated equal. And accounts of the harsh working conditions in the aluminum smelting plant and the environmental degradation caused by the wastes it generated are well documented.

Seeing Badin afresh through this new historical lens, and considering the timeframe of its founding, I came to realize that the town’s planners must have been disciples of Ebenezer Howard, who founded the Garden City movement in England during the first decade of the 20th century. While not formally a garden city in the textbook sense, Badin had many of its salient features, including a unique blend of suburban and urban form, in a village sort of way. As an aspiring planner attracted to both the natural and built environments, I was thrilled to learn that this town that had stirred my earliest interest in urban planning was a legacy of the Garden City movement on this side of the Atlantic.

But then I discovered the works of the great urbanist Jane Jacobs. In addition to her gift for opening our eyes to the merits of strong urban places, and describing in plain and simple terms the intricate ecosystem that makes them possible, she was also an acerbic critic of the suburban style of planning that the Garden City movement had ushered in. Of Ebenezer Howard and his garden cities she said:

“His aim was the creation of self-sufficient small towns, really very nice towns if you were docile and had no plans of your own and did not mind spending your life among others with no plans of their own.”

Ouch! But despite the condescending nature of that remark, I couldn’t help but find truth in this additional critique:

“(I)n each case the plan must anticipate all that is needed and be protected, after it is built, against any but the most minor subsequent changes.”

This seemed to me a fair assessment of how the Garden City movement had played out – that once the original economic reasons for their existence went away, as inevitably happened when the industries they were dependent on disappeared, the towns that remained were left with one of two choices. They could either morph into something new to survive (many of the original garden cities in England became more affluent bedroom communities for commuters working in nearby urban centers), or they could resort to stasis and eventual decline, fighting the very adaptations that might save them.

Sadly, I watched this gradual decline in Badin after Alcoa shuttered its operations there in 2002. Without adapting – and lacking the diverse entrepreneurial ecosystem that Jacobs described as the key to resiliency in more complex urban economies – Badin, the celebrated model company town of 1920, seemed to have become just another failed economic model in 2020.

Or had it? Were Badin’s best days really behind it, or was this merely a temporary lull before the town reinvented itself? And perhaps a more fundamental question: was Badin even worth saving in an economic era that favors urbanity and the concentration of talent in more dense environments? That’s a question facing many small towns in America today, including those not endowed with Badin’s unique gifts.

It’s also a question being asked in suburban neighborhoods in major cities like Charlotte, built decades after Badin but influenced by many of the same design principles of the Garden City philosophy. Today, those close-in neighborhoods are wrestling with the challenge of how to retrofit themselves for continued relevance, while maintaining at least some of the DNA of their original urban form.

And some of that DNA is indeed worth fighting for. Despite the condescension and derision that some urbanists heap on small towns and suburban communities, there are many elements of a less dense form of urbanity that, if designed well, still deserve a place in the planning toolbox. Bill Fulton noted this in his essay on Auburn, New York:

“(I)t’s hard for anybody who grew up in America in the last half-century (to understand) how self-contained — how totally complete — towns like Auburn were. And not just in the 19th Century or during World War I, but as recently as the 1960s and ‘70s.”

He went on to note the bias of many urbanists today:

“Many urban planners grow up in big cities and they have a big-city perspective on what urban life should be like. But Auburn endowed me with a deep understanding that the benefits of urban life — close proximity to everything you need, the ability to walk and bike everywhere, a rich tapestry of everyday life — did not exist only in big cities. They could exist in small towns as well, so long as those towns had jobs as well as people and could hang on to culture, entertainment, sports, and other activities indigenous to the place.”

To be completely honest, though, many small towns and much of suburban America never fully developed the complete array of activities Fulton describes, and a further reality is that many of those activities are dependent on a greater density than some of these places were designed to accommodate. More important, too many of these communities were unable to sustain the jobs that were essential to their survival – or at least the connections to jobs (through transportation, reliable internet, and other forms of infrastructure) necessary to maintain them as viable places to live.

But instead of completely abandoning their identities, these communities should view these challenges as structural issues to address in adapting for the future, much like shoring up the foundation of an old house to ready it for rehab. In the same way that tear-downs of older houses are decimating the unique character and authenticity of historic neighborhoods, abandoning these places and their intrinsic character altogether for the promise of something new risks unraveling an important thread in our urban fabric.

To be sure, strengthening their foundations will likely involve dramatic change, including selective densification, the building of more affordable housing options, and bringing down barriers of exclusivity by creating stronger connections to surrounding areas. But it’s also true that the preservation of existing resources, both built and natural, should be part of the equation as well in order to maintain some element of authenticity and the beneficial services that natural resources in these places provide. Not every call to maintain community character should be viewed as just another kneejerk, NIMBY response to change.

Planners today talk eloquently about the concept of the “transect,” the idea that a healthy urban ecosystem is made up of different forms of density, “feathering out” from the denser core. Yet I sometimes worry that not enough thought and effort is being dedicated to how to design the “village urbanity” that I believe is essential to make this feathering work. And in an era of growing concerns about climate change, indiscriminate density without a corresponding concern for preserving open space and the urban tree canopy has the danger of becoming just a denser version of sprawl.

That’s why I believe places like Badin have as much to teach us as planners as the elegant “sidewalk ballet” that Jane Jacobs described in her beloved Greenwich Village. Both urban forms are essential to a vibrant and healthy urban ecosystem, particularly on a regional scale. And it doesn’t seem a coincidence that both lay claim to the term “village.”

Jeff Michael is Director of the UNC Charlotte Urban Institute. His story first appeared on the institute’s website.