Jackie Estes put a lot of miles on her Dodge Ramcharger shuttling her two sons and nephew from Pearland out to AstroWorld as often as three times a week during summers in the late-1980s. Estes is a small woman — she stands about 5 feet, 4 inches — and sat on a pillow to see clearly over the steering wheel and dashboard of the large SUV. In the ‘80s, carmakers offered fewer options for driver’s-seat adjustment than today, and in the Ramcharger, up and down wasn’t one of them.

Typically, Estes pulled up just before the parks’ gates opened, and the three boys — season passes gripped tight — piled out. For the first hour or two of the day, the cousins largely had AstroWorld to themselves. With the park still empty, they waited in no lines and could ride any of the roller coasters — usually Greezed Lightin’ — four or five times without exiting the ride. They stopped just briefly, following the abrupt end — which sent the trio rocking first forward against the safety bars, then back against the seat — with a raised hand they’d signal, “we’re good, let’s go again,” to the ride’s teen operator. They felt like they owned the place.

I know all of this because Jackie Estes is my aunt. She later sold that Ramcharger to my dad, who drove it for a few years before passing it on to me and then my brother for a time when we were in college. My cousins and I grew up in Pearland. Back then, the population hadn’t yet cracked 20,000, and the city felt more like a small town — in many ways, not in a good way.

But growing up, we were fortunate — more than I was aware — to be able to visit AstroWorld regularly during those summers. We also got to watch the Astros play in the Astrodome, just on the other side of 610. We’d yell down to José Cruz in left field, mimicking the team’s PA announcer: “JOSE CRUUUUUUUUUUZZZ!” And, inevitably, he would turn and give us a small, sly wave. Later, at home in the backyard, we’d imitate Cruz’s distinctive batting stance during impromptu games that were part pretend play, part goofing off and part actual baseball. When the All-Star Game was played at the Dome in July 1986, we went to the Home Run Derby and watched (mouths agape, obviously) Darryl Strawberry rocket a ball off a speaker hanging 350 feet from home plate and 140 feet above right field. (While official, those dimensions don’t come close to conveying the impressiveness such a shot still holds in my memory, which was formed from a 10-year-old’s perspective.)

According to the Houston Chronicle columnist Fran Blinebury, the ball “might have gone right through the wall and landed in downtown Pearland if it hadn’t kicked off one of the loudspeakers suspended from the ceiling.” (Though it should be noted, Pearland has never had a downtown.)

A few months after the All-Star Game, Strawberry and the Mets edged the Astros in the National League Championship Series, winning a decisive Game 6 at the Dome. It was an epic game that went 16 innings, but Houston missed a shot at the World Series. After the Astros lost, my mom found me in the garage crying. I can remember the frustrated annoyance in her voice as she demanded to know: “What is wrong with you?”

Hers was a relevant response to what she must have seen as an irrational reaction to a game played by grown men. But, when I was a kid, I loved the Astros, and at that moment, I hated the Mets (Ray Knight, in particular) for winning. It was a slight I took personally. The Astrodome, the Astros and AstroWorld were more than minor characters in the story of my childhood, but I didn’t know their origin stories. I knew names like Nolan Ryan and Mike Scott, and earlier players like Joe Morgan, J.R. Richard and Jimmy Wynn. But I didn’t know who Roy Hofheinz was, or the names George Kirksey, Craig Cullinan, or R.E. “Bob” Smith. Not to mention Quentin Mease or Eldrewey Stearns.

In his book “The Sports Revolution: How Texas Changed the Culture of American Athletics,” Frank Andre Guridy provides a broader context for how the growing popularity of sports such as football and basketball, the rise of television and landmark legislation converged in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s to change sports, popular culture and society in America. And the significant role sports entrepreneurs from Texas played in all of this. But, Guridy points out, they could not have achieved their goals if it wasn’t for the civil rights movement and the efforts of activists.

In the sheltered, suburban cocoon of my life in the 1980s, I consumed sports — and much of the world — through a filter that removed the messy, ugly and complex realities — as well as the “innovation and transformation of the previous decades,” which Guridy, an associate professor of History at Columbia University, writes, “were overrun by commercialism and stripped of the potential for more radical visions of sport and social change.”

The rise of the Texas sports entrepreneurs

Following World War II, Texas college football came to prominence on the national stage. At the same time, wealthy Texas oilmen seemed to appear from nowhere. Many Americans headed to states in the west and the Sunbelt after the war, and professional sports leagues followed. “California was at the center of this new sporting frontier, where national pro sports enterprises sought to intrude upon smaller-scale regional leagues.” Texas sports entrepreneurs, as Guridy refers to them, wanted a piece of that new frontier.

The sports revolution was fueled by oil money, with members of the “oil elite,” including Lamar Hunt, Bud Adams and Clint Murchison Jr., spearheading the arrival of professional sports in Texas. Members of the oil elite and other sports entrepreneurs from the Lone Star State wanted to use professional sports to put Houston and Dallas “on the map.” That, in turn, would put more money in their already bulging pockets. But they would also “transform the ways sports was consumed by the public."

Houston, Guridy writes, was transformed “from an oil and cattle town to a booming metropolis with new industries such as aerospace and sports” in the decades following the Second World War. During this, the city “played a catalyzing role in the making of the Sunbelt.”

Texas’ sports entrepreneurs “did more than bring pro sports to the Southwest,” writes Guridy. “They changed American sports spectating by refashioning the ubiquitous institution of the stadium from a small, functional venue to a massive, comfortable leisure space that resembled a large living room.”

They found a way “to have the cocktail party with the business partners, the clients, and the sexy ladies at the ballpark itself. It is not by accident that the first three stadiums constructed with the now-ubiquitous luxury boxes in the late 1960s and early 1970s were conceived by Texas-based professional franchise owners.”

Judge Hofheinz and the Eighth Wonder

In Houston, Roy Hofheinz, a former Harris County judge and a two-term mayor of the city, tirelessly crusaded to bring his vision for the “Eighth Wonder of the World” to life. Doing that required a lot of money and the support of Harris County voters. Jim Crow was still alive in the racially segregated South, but Hofheinz, Kirksey and other members of the Houston Sports Association were ready to take progressive action that other — less farsighted — Texas sportsmen had not. Local Black rights activists from Texas Southern University were integral as well.

“In order to combine their business acumen with their passion for sports, they could not simply acquiesce to the state's traditions of racial exclusion. A new social order was on the horizon, and pro sports expedited its arrival.”

The Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling in 1954 may have segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, integration of schools in the South was slow, to put it mildly. And with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 a decade away, segregation of public facilities and accommodations remained.

At Jeppesen Stadium, a public high school facility managed by the Houston Independent School District, fans were segregated by race. In 1961, the TSU track team boycotted the Meet of Champions held by the University of Houston at Jeppesen because of the policy.

Guridy writes that, while the boycott grabbed some attention, Black activists’ “main target” was Adams’ Houston Oilers, the franchise that began playing in 1960 after Adams, Hunt and six other owners established the American Football League. The Oilers played their home games at Jeppesen, where Black fans were “relegated to end zone seating, usually the least attractive sections in a football stadium, during games when whites were present.” Adams was criticized by the Houston Informer and the Houston Forward Times — African American newspapers — for the small number of Black players on the Oilers’ roster and for “refusing to desegregate seating at Oilers home games.”

During the 1961 season, activists from the local chapter of the NAACP “joined a broader national campaign to combat discrimination and segregation in sports” by picketing outside of Oilers games at Jeppesen. Lloyd C.A. Wells, a local Black sportswriter and photographer for the Informer, published photos of Black players who crossed the NAACP picket line and Black fans who attended Oilers games. (The Oilers played at Jeppesen until 1964 when the team moved its games to Rice Stadium.)

Adams took no action, but the Houston Sports Association (HSA), which was pursuing an MLB franchise for the city, did. The HSA’s Kirksey “assured the black press” that the Colt 45s “‘would be Houston’s team without any regard to racial preferences.’”

“The main catalyst for this cultural and social transformation,” Guridy writes in his book, “was the HSA’s campaign to build the world’s first indoor stadium.” After the HSA landed its MLB franchise, civic boosters led by Hofheinz needed taxpayer support — $31 million — to publicly finance what would be the Astrodome. It’s at this point that Quentin Mease enters Guridy’s story.

Mease, who was director of the South Central YMCA, believed sports could lead to “racial understanding in Houston,” and Hofheinz approached him for help in getting Black Houstonians to back the Astrodome bond vote in 1961. Mease agreed on the condition the Dome “would be desegregated in the stands, on the field, and in hiring practices.”

With Hofheinz’s assurances of a desegregated Dome, an alliance was formed with Mease and other Black leaders and activists in the city, including Eldrewey Stearns, the leader of the Progressive Youth Association, that “accelerated the end of racial segregation in the Houston sports scene.”

Stearns, who passed away last December, led student demonstrators from TSU in the first sit-in west of the Mississippi on March 4, 1960, when the group targeted an all-white lunch counter at Weingarten’s on Almeda. The students staged another sit-in the following week, and within six months, 70 lunch counters in the city were desegregated.

“The reason you don’t remember seeing or hearing much about Houston’s activism during this period,” Stephen Klineberg explains in “Prophetic City: Houston on the Cusp of a Changing America,” “is that the owners of the local TV, radio, and newspapers — most of which were controlled by Jesse Jones’s nephew and heir, John T. Jones — conspired to suppress any coverage of the protests.”

Klineberg also depicts the role the Reverend Bill Lawson, who had just arrived at TSU, played in the media blackout:

“When several TSU students asked for (Lawson’s) blessing and guidance as they prepared to engage in the city’s first serious civil rights protests, he resisted. ‘Their parents had worked so hard to get them into this school,’ Lawson told Steve Klineberg. ‘If the kids were arrested, they’d get kicked out of school. I was afraid the dogs and fire hoses would be brought in. I was sure they’d get beaten, or worse. I didn’t want anything to happen to those kids.’

The reverend told Klineberg that Stearns, who had been severely beaten by Houston Police two years earlier, said to him, “we are going to go ahead with or without your blessing.’ “So when Jones and others from the Houston business community approached Lawson with a strategy they hoped would minimize the likelihood of the kind of violence that had occurred in other Southern cities, Lawson offered his support; their plan was to engineer a media blackout on the imminent civil rights protests.”

Jones worried media coverage of local protests would lead to the type of police violence seen in other Southern cities, and if America viewed Houston as “no different from the other racist Southern towns … that would be bad for business.”

“If we actively try to prevent the desegregation of our shops, restaurants, and theaters, Houston will be seen as just another dying Southern town desperately clinging to the old ways in the face of inevitable change.”

Guridy mentions the media blackout in his book, but he doesn’t mention Jones; however, I would guess it was no coincidence that his interests squared with those of the Houston Sports Association.

The revolution that followed

It took three years to build the Astrodome, which opened in 1965 and “helped catalyze a social and cultural revolution in Houston,” according to Guridy. By that time, the segregation of Buffs Stadium and Jeppesen Stadium was no more, and other sports programs followed the Astros’ lead.

In his book, Guridy mentions the American Football League hurriedly moving its All-Star from New Orleans to Houston in 1965 after 21 African American players threatened to boycott the game because of the discrimination, open hostility and blatant racism they faced in New Orleans. Ironically, the game was played at Jeppesen.

In 1962, the University of Houston began admitting Black students and, in the mid-‘60s, was one of the first colleges in Texas to recruit Black athletes. Guridy writes about San Antonio’s Warren McVea, who was signed by UH football coach Bill Yeoman as the school’s first African American football player. Meanwhile, Guy Lewis brought in Elvin Hayes and Don Chaney, two standout basketball players from Louisiana.

Lewis was one of the first coaches in the South to recruit African American players, and just a few years later, a 14-0 UH squad led by senior stars Hayes and Chaney would square off against Lew Alcindor and UCLA at the Astrodome in the “Game of the Century” — the first regular-season NCAA game televised in prime time. The second-ranked Cougars knocked off the top-ranked Bruins and remained No. 1 until dropping a rematch with UCLA in the Final Four. UH’s recruitment of African American players not only elevated the program to national prominence, it also led to one of the most significant games in college basketball history, one that drew close to 53,000 fans to the Astrodome and a huge TV audience in homes across America, proving the sport’s worth as a TV commodity.

Integration isn’t the same as equality

Guridy includes a passage from Mease’s autobiography, “On Equal Footing,” in which he wrote: “The bargain to trade black support of the Astrodome for a desegregated facility paid off. Sports were bringing people together, and all of this promoted better understandings. These were not isolated incidents, either; They meshed into the fabric of how we were affecting change throughout the city.”

A well-known photo from the groundbreaking ceremony for the Astrodome features Hofheinz and Harris County commissioners holding six-shooters in place of the obligatory ceremonial shovels. During the photo op, instead of shoveling a scoop of dirt, the group of white men fired into the ground. Guridy’s book features a photo found buried in Mease’s papers at the University of Houston in which he and two other Black community leaders, A.E. Warner and James F. Brooks, are holding six-shooters of their own while taking part in the ceremony. “The optics at the groundbreaking on January 3, 1962,” Guridy writes, “were indicative of the inclusive spirit of the Dome project.”

Without a doubt, Guridy told an online audience last month during his presentation “The Dome and the Desegregation of Sports in Houston,” the Astrodome “ushered in a new day in the world of Houston sports.” But, Guridy asked, was Mease right about its ability to usher something greater? Or, did Mease “too confidently predict that racial desegregation would bring about substantive equality in Houston?”

Here’s his answer:

“What is clear is that more often than not, in the sports world during the 1960s and 70s, ‘equality meant integration,’ meaning that formerly marginalized populations achieved a degree of unprecedented inclusion in predominantly and exclusively white athletic spaces. But they did so under the supervision of more powerful white male team owners, general managers and coaches. Athletes from marginalized backgrounds, black and otherwise, could occupy spaces on team rosters — and even become superstars — but they often did not ascend to the level of management, where the benefits of their labor were ultimately determined.”

Klineberg offers this perspective on desegregation and equality in the city: “With the collusion of the local media, the student protests, the marches, the sit-ins, and the beatings were given virtually no coverage. Houston’s business community quietly desegregated the lunch counters and movie theaters, off-camera and outside the reach of local and national media.

That successful effort to desegregate public accommodations did very little to improve the quality of life in Houston’s black communities. It didn’t improve the segregated public schools. It did nothing to stop the refineries and industries from continuing to dump their toxic wastes in black neighborhoods.”

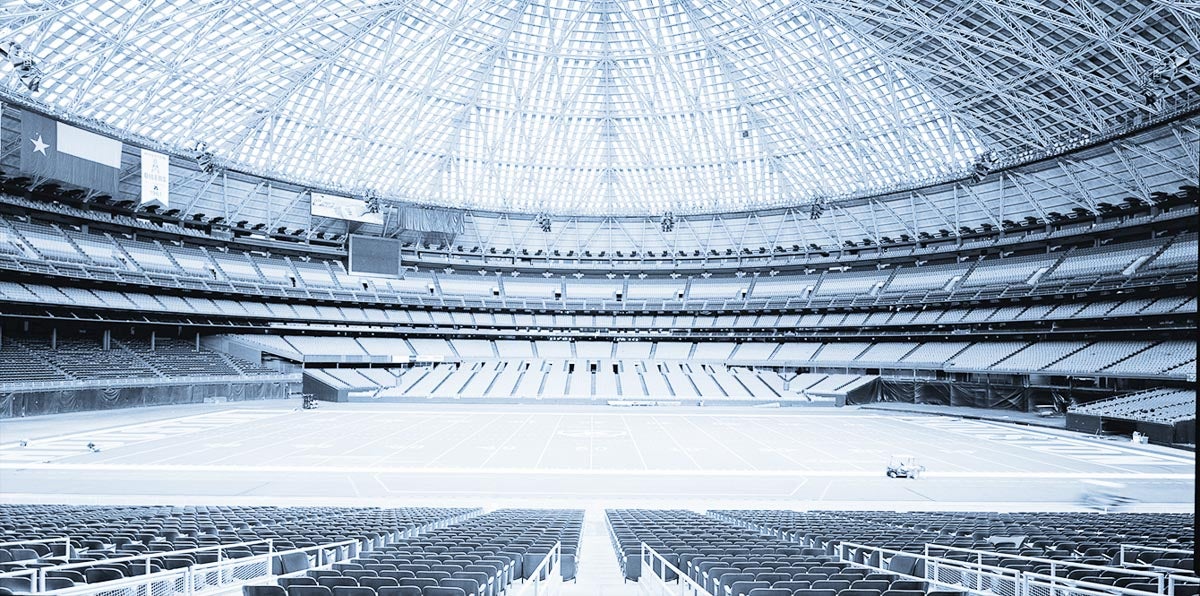

What will become of the Astrodome?

The long, slow decline of the Astrodome is well-documented. Bud Adams and the Oilers left for Tennessee in 1996. A few years later, the Astros left for Enron Field downtown. There’s not a trace left of AstroWorld — the park closed in 2005 and was demolished soon after. The Astrodome still stands, but it’s only a husk of what it was once. For now, the fate of the Eighth Wonder of the World remains in limbo — plans to renovate or remake it are too costly, yet demolition isn’t widely supported, mostly for sentimental reasons. While the future of the Domes isn’t clear, there’s no doubt its past is a fascinating and significant part of Houston history.