So far, 2017 appears to be a quiet year for Zika in Houston. Early reports that six Texas women tested positive for the virus this year, were later said to actually be inconclusive.

Tackling the threat of Zika virus, which can cause serious birth defects, became a priority in 2016 when the city and county responded with campaigns and a request for state and federal support and funding. The city health department did targeted, door-to-door sweeps armed with educational materials about minimizing exposure to risk. It also cleared more than 35,000 illegally dumped tires and other debris over the summer to remove potential mosquito breeding sites. In 2017, Houston again geared up to tackle the issue. With a total of 33 recorded cases of Zika in Houston since 2015, the city said none have been reported so far in 2017, but is it out of the woods?

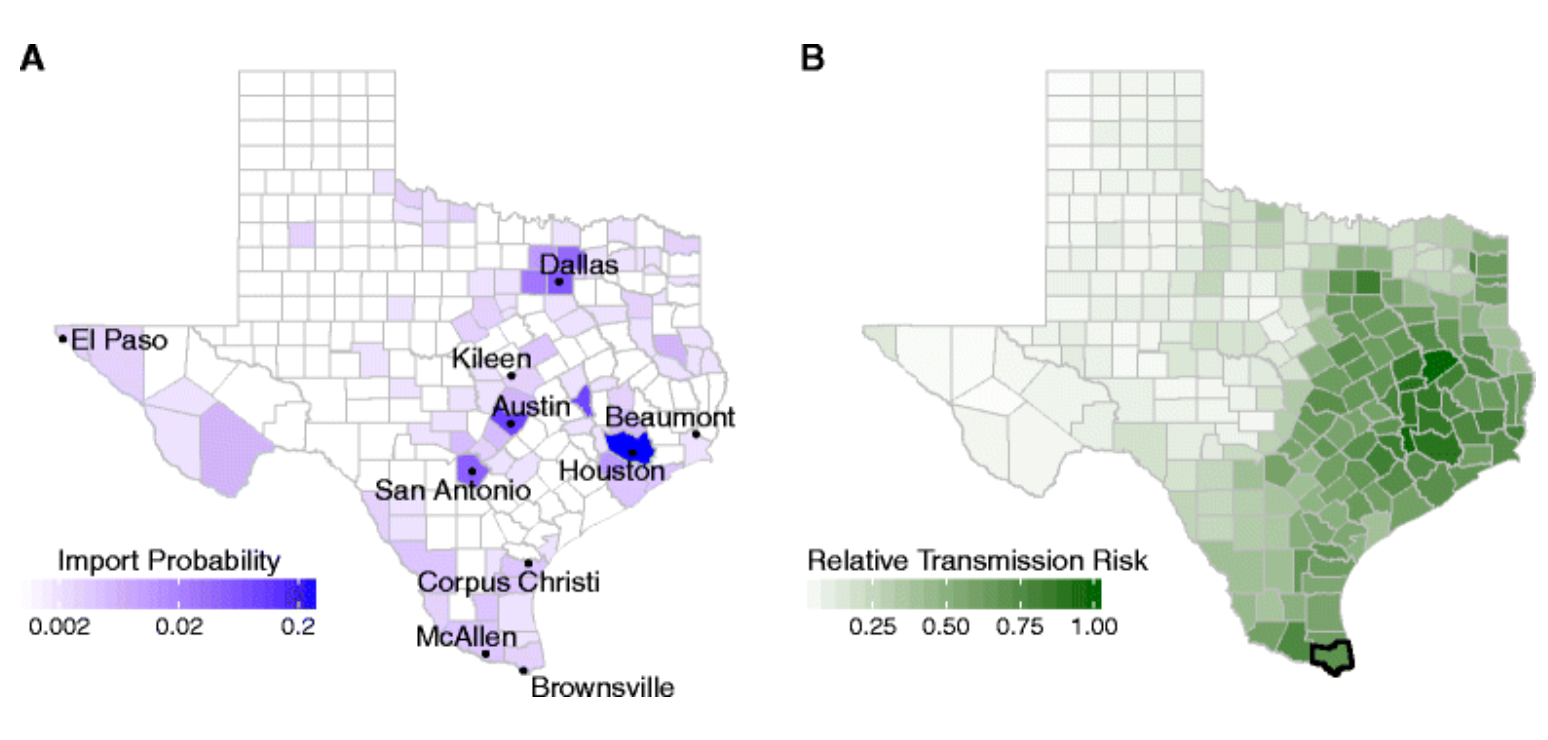

Probably not entirely. A study published in May in BMC Infectious Diseases found that counties along the U.S.-Mexico border and the Houston metropolitan area had the highest risk for Zika transmission in the state. Using factors like the level of urbanization, mobility patterns and socioeconomic status, the team of researchers from across the country created a new county-level risk assessment measure as well as local surveillance triggers that signal the threshold at which a cluster of reported cases carry the risk of an epidemic. Because an estimated 80 percent of Zika cases don't come with visible symptoms, the report notes, it's likely the reporting rate won't match the actual transmission rate.

"A policymaker has to weigh the costs of false positives–resulting in unnecessary fear and/or intervention–and false negatives–resulting in suboptimal disease control and prevention–complicated by the difficulty inherent in distinguishing a false positive from a successful intervention," writes the report, authored by eight researchers, including Lauren A. Castro, Spencer J. Fox, Xi Chen and Kai Liu from the University of Texas at Austin.

Houston appears particularly vulnerable in Texas. "Houston's Harris County has 2.7 times greater chance than Austin's Travis County of receiving the next imported case," according to the report. When it comes to the likelihood of local transmission, Harris County also had a relatively high risk for not only transmission but for the potential triggering of an epidemic.

Tracking the virus' spread from 2016, Dr. Peter Hotez, the founding dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine, noted in a recent blog post that the virus comes in waves. Hundreds of thousands of infections spread across Brazil in early 2016 with more in Colombia and Venezuela. Then a second wave emerged in the Caribbean, fueling fears along the United State's southern edges. By 2017, he said, the epidemics there had largely ended.

Still, he cautioned, there are new hot spots popping up and with Mexico's rainy season underway, he said, "we’ll still need to be vigilant for the return of Zika virus infection there. And since Mexico and South Texas are linked in so many ways, we need to continue monitoring Zika virus infection."

But he wasn't ready to make any predictions. "For all these reasons, what will happen in terms of Zika virus infection in Texas may still be anyone’s guess," he wrote. From his work on other similar viruses also transmitted by mosquitoes or ticks, for example, he warned, "one of the lessons learned about arbovirus infections, such as West Nile virus infection and dengue is that they do eventually return. So even if Zika virus does not return in a big way to the Western Hemisphere in 2017, there’s still 2018, 2019, or 2020, and so forth."

Houston, with its mix of poverty and rain and large, international populations, remains vulnerable going forward.